Gynecologic cancers contribute to approximately 15% of cancer survivorship care for women. Many patients share surveillance visits between their gynecologic oncologist and their ob.gyn. or primary care physician to capitalize on preexisting relationships and ensure the provision of comprehensive wellness care. Providing high quality surveillance care is challenging because it requires vigilance in the detection of recurrence but also avoidance of unnecessary, costly, and inaccurate testing.

The oncologic benefits for various surveillance guidelines are not well established by prospective studies. However, in updated surveillance recommendations, the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) takes available data, costs, and benefits into consideration.1 The guidelines, authored by Ritu Salani, MD, provide an excellent resource for understanding appropriate testing and evaluation during surveillance care.

As with screening, the goal of surveillance is to detect recurrence and, thereby, extend survival or palliate symptoms.The cornerstone of a surveillance visit is a thorough symptom assessment. Positive reporting of symptoms remains the most sensitive method for detecting recurrences; therefore, patients should be educated and quizzed on common recurrence symptoms. For example, endometrial cancer most commonly recurs in the vagina with symptoms of vaginal bleeding or discharge. Lower extremity swelling can signify pelvic sidewall recurrences and abdominal bloating or pain can signify peritoneal recurrence of ovarian or endometrial cancer.

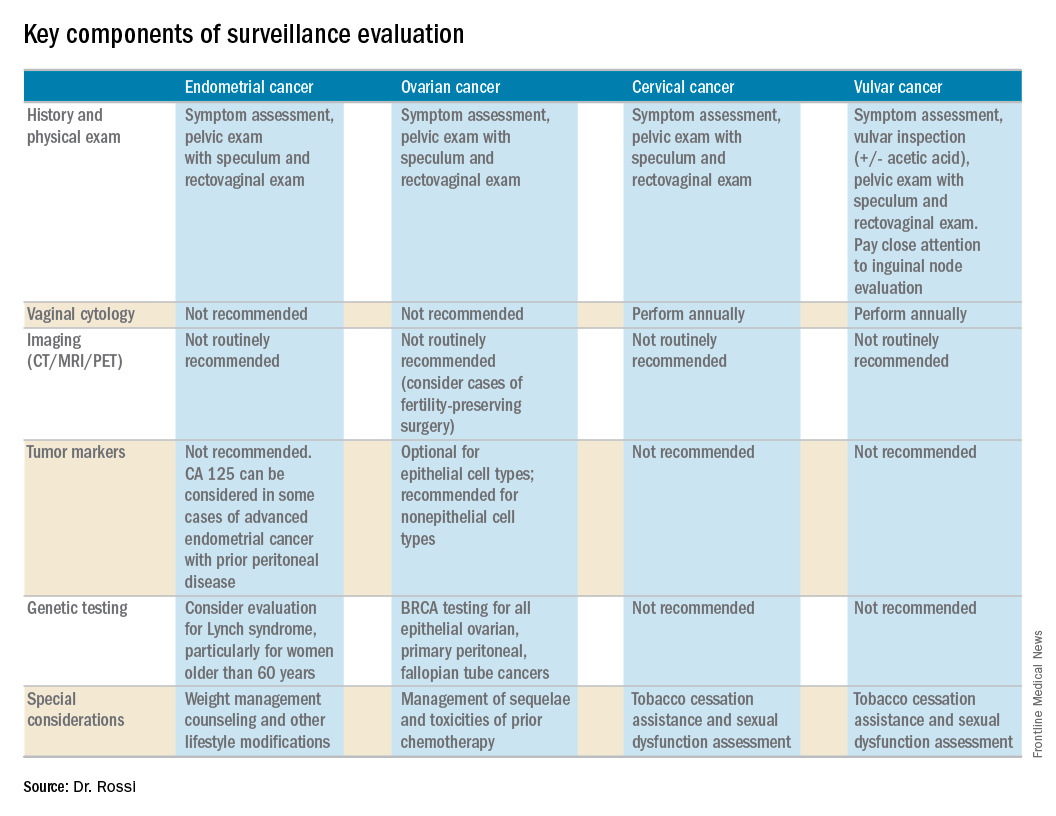

All women who are undergoing surveillance for gynecologic cancers should receive physical examinations that include a pelvic exam with a speculum and bimanual exam with rectovaginal exam. Many locoregional recurrences are salvageable for most gynecologic cancers, which is not true for most distant recurrences, emphasizing the importance of pelvic examinations.

In addition to surveillance of recurrence, these visits should focus on risk modification – tobacco, obesity, bone demineralization – as well as preventive health strategies, such as vaccinations, nongynecologic cancer screenings, and cardiovascular disease intervention. Clinicians should also ask about sequelae to cancer therapy, such as neuropathy, lymphedema, sexual dysfunction, depression, and fatigue.

Endometrial cancer

Endometrial cancer recurs most commonly among women with a history of advanced stage cancer or early stage disease with high/intermediate risk factors, but all survivors should be evaluated regularly for recurrence. The vagina is the most common site for recurrence. Fortunately, many vaginal recurrences can be cured with salvage therapies.

Women with the lowest risk for recurrence (stage IA, grades 1 and 2 disease) who did not originally qualify for adjuvant therapy can be followed every 6 months for 2 years and then annually.

Vaginal cytology is no longer recommended for the routine surveillance of endometrial cancer because of its poor sensitivity in detecting recurrence and low positive predictive value (particularly after vaginal radiation).2 Any suspicious lesions identified on speculum examination should be biopsied, rather than sampled with cytologic smear. Routine imaging (with CT or PET/CT) and cancer antigen (CA) 125 tumor marker assessment is not supported unless the initial stage was advanced. These tests should be reserved for confirmation of concerning symptoms or examination findings.

This group of patients has particular survivorship needs with respect to obesity interventions. Obesity is associated with poor prognosis from endometrial cancer, and patients should be counseled about this and offered strategies for weight loss and lifestyle modification. Lynch syndrome testing and colon cancer screening are also an important consideration in this population.

Ovarian cancer

Ovarian cancer recurrence rates are high, and, while salvage therapies are rarely curative, enduring responses may be achieved in some patients, making surveillance visits critical. The SGO recommends surveillance visits every 3 months in the first 2 years, every 4 months in year 3, and then every 6 months for an additional 2 years. At these visits, patients should be queried about symptoms with particular emphasis on peritoneal signs (bloating, distension, gastrointestinal disturbance, and abdominal pain) as most recurrences will be within the peritoneal cavity.

CA 125 tumor marker elevation during the surveillance phase may signal recurrence prior to the development of symptoms but initiating chemotherapy early because of elevations in CA 125 does not improve survival.3 However, in the platinum-sensitive population with a longer disease-free interval, earlier detection of recurrence by CA 125 may identify patients in whom complete secondary cytoreduction is more attainable and is associated with improved survival.4 Therefore, the SGO suggests that CA 125 assessment is optional. The benefits and limitations of earlier detection of recurrence should be discussed with each patient. This recommendation differs for survivors of nonepithelial ovarian cancers (such as germ-cell or sex-cord stromal), in which case the measurement of the appropriate tumor markers (such as alpha-fetoprotein, human chorionic gonadotropin, and inhibin) should be performed routinely as part of surveillance evaluation.

Evidence does not support routine imaging (such as CT or PET). It should be reserved as a confirmatory measure for patients with concerning symptoms, examination findings, or elevations in tumor markers. When ovarian cancer has been treated with fertility-preserving surgery in women of younger reproductive ages, pelvic ultrasounds may be used as part of their surveillance care to monitor retained ovaries and pelvic structures.

BRCA-gene testing should be offered to all women with epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer as it impacts future cancer risk, as well as chemotherapy selection.5

Cervical cancer

In the first 2 years after completing primary treatment for cervical cancer, those at high risk for recurrence (including those who were recommended to adjuvant therapy) should be evaluated every 3 months for 2 years, followed by visits at 6-month intervals for an additional 3 years. Low-risk patients can be followed every 6 months for 2 years, followed by annual visits thereafter.

Pap testing should be performed annually, rather than at each surveillance visit. It should not to detect recurrence – for which it has poor sensitivity and specificity – but rather to detect new HPV-related dysplasia.6

Many patients with cervical cancer have a tobacco use history, placing them at risk for other cancers. Educate patients about the risk and provide cessation assistance.

Vulvar cancer

Prognosis for early stage vulvar cancer is very good; however, local recurrences are common (as much as 40%) in the 10 years following diagnosis.7 It is important to thoroughly inspect the vulva, vagina, and cervix at each surveillance visit. In high-risk patients, examinations should take place every 3 months for the first 2 years after completing primary treatment and every 6 months until 5 years post treatment. Low-risk patients can be followed every 6 months for 2 years and annually thereafter.

Identification and early treatment of dysplasia is important. Careful attention should also be made to palpation of the inguinal nodal regions. One in 10 women will have a late recurrence (greater than 5 years), so vulvar inspections should continue at least annually for the remainder of a woman’s life.

Dr. Rossi is an assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Mar 31. doi: 10.1016/j.ygno.2017.03.022.

2. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Jan;121(1):129-35.

3. Lancet. 2010 Oct 2;376(9747):1155-63.

4. Gynecol Oncol. 2009 Jan;112(1):265-74.

5. Gynecol Oncol. 2015 Jan;136(1):3-7.