Antenatal corticosteroid treat-ment prior to preterm birth is the most important pharmacologic intervention available to obstetricians to improve newborn health. Antenatal corticosteroids reduce preterm newborn morbidity and mortality.1 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recently has summarized updated recommendations for the use of antenatal steroid treatment.2

ACOG guidance includes:

- “A single course of corticosteroids is recommended for pregnant women between 24 0/7 weeks and 33 6/7 weeks of gestation, including for those with ruptured membranes and multiple gestations.” This guidance is supported by many high-quality trials and meta-analyses.1

- A single course of corticosteroids “may be considered for pregnant women starting at 23 0/7 weeks of gestation who are at risk of preterm delivery within 7 days.”

- “A single repeat course of antenatal corticosteroids should be considered in women who are less than 34 0/7 weeks of gestation who have an imminent risk of preterm delivery within the next 7 days and whose prior course of antenatal corticosteroids was administered more than 14 days previously.” A repeat course of corticosteroids could be considered as early as 7 days from the prior dose.

- No more than 2 courses of antenatal steroids should be administered.

An important new ACOG recommendation is:

- “A single course of betamethasone is recommended for pregnant women between 34 0/7 and 36 6/7 weeks of gestation at risk of preterm birth within 7 days, and who have not received a previous course of antenatal corticosteroids.”

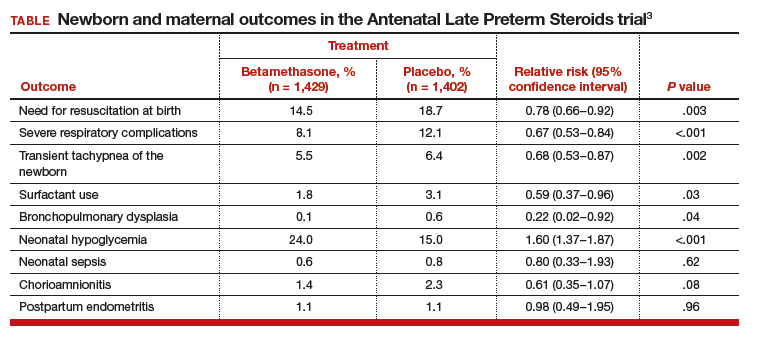

This recommendation is based, in part, on a high-quality, randomized trial including 2,831 women at high risk for preterm birth between 34 0/7 and 36 6/7 weeks of gestation who were randomly assigned to receive a course of betamethasone or placebo. The newborn and maternal outcomes observed in this study are summarized in the TABLE.3

A few points relevant to the Antenatal Late Preterm Steroids study bear emphasizing. The women enrolled in this trial were at high risk for preterm delivery based on preterm labor with a cervical dilation of ≥3 cm or 75% effacement, spontaneous rupture of the membranes, or a planned late preterm delivery by cesarean or induction. No tocolytics were administered to women in this study, and approximately 40% of the women delivered within 24 hours of entry into the trial and only received 1 dose of corticosteroid or placebo.

Women with multiple gestations, pregestational diabetes, or a prior course of corticosteroids were not included in the trial; therefore, this study cannot guide our clinical practice for these subgroups of women. Of note, betamethasone should not be administered to women in the late preterm who have chorioamnionitis.

Related article:

When could use of antenatal corticosteroids in the late preterm birth period be beneficial?

The investigators calculated that 35 women would need to be treated to prevent one case of the primary outcome: a composite score of the use of respiratory support. Consequently, 34 fetuses who do not benefit from treatment are exposed in utero to betamethasone. Long-term follow-up of infants born to mothers participating in this study is currently underway.

A recent meta-analysis of 3 trials including 3,200 women at high risk for preterm delivery at 34 0/7 to 36 6/7 weeks of gestation reported that the corticosteroid administration reduced newborn risk for transient tachypnea of the newborn (relative risk [RR], 0.72; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.56−0.92), severe respiratory distress syndrome (RR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.33−0.94), and use of surfactant (RR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.38−0.99).4

The recommendation to offer a single course of betamethasone for pregnant women between 34 0/7 and 36 6/7 weeks of gestation at risk for preterm birth has not been embraced enthusiastically by all obstetricians. Many experts have emphasized that the known risks of late preterm betamethasone, including neonatal hypoglycemia and the unknown long-term risks of treatment, including suboptimal neurodevelopmental, cardiovascular, and metabolic outcomes should dampen enthusiasm for embracing the new ACOG recommendation.5 Experts also emphasize that late preterm newborns are less likely to benefit from antenatal corticosteroid treatment than babies born at less than 34 weeks. Hence, many late preterm newborns will be exposed to a potentially harmful intervention and have only a small chance of benefiting from the treatment.6

Many neonatologists believe that for the newborn, the benefits of maternal corticosteroid treatment outweigh the risks.7–9 In a 30-year follow-up of 534 newborns participating in antenatal corticosteroid trials, treatment had no effect on body size, blood lipids, blood pressure, plasma cortisol, prevalence of diabetes, lung function, history of cardiovascular disease, educational attainment, or socioeconomic status. Corticosteroid treatment was associated with increased insulin secretion in response to a glucose load.10 In this study, the mothers received treatment at a median of 33 weeks of gestation and births occurred at a median of 35 weeks. Hence this study is relevant to the issue of late preterm corticosteroid treatment.

Balancing risks and benefits is complex. Balancing immediate benefits against long-term risks is most challenging. Regarding antenatal steroid use there are many unknowns, including optimal dose, drug formulation, and timing from treatment to delivery. In addition we need more high-quality data delineating the long-term effects of antenatal corticosteroids on childhood and adult health.

Read about 3 options to use in your practice