Role and authority of the ABMS and related boards

Many physicians are frustrated with the perceived autocratic nature of their boards—boards that lack transparency, do not solicit or allow input from practicing physicians, and are unresponsive to physician concerns.

According to Susan Ramin, MD, ABOG Associate Executive Director, ABOG is leading in a number of these areas, including:

- rapidly disseminating clinical information on emerging topics, such as Zika virus infection and opioid misuse

- offering physician choice of testing categories

- exempting high scorers from the secured written exam, which saved physicians a total of $881,000 in exam fees

- crediting physicians for what they already are doing, including serving on maternal mortality review committees, participating in registries, and participating in the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM)

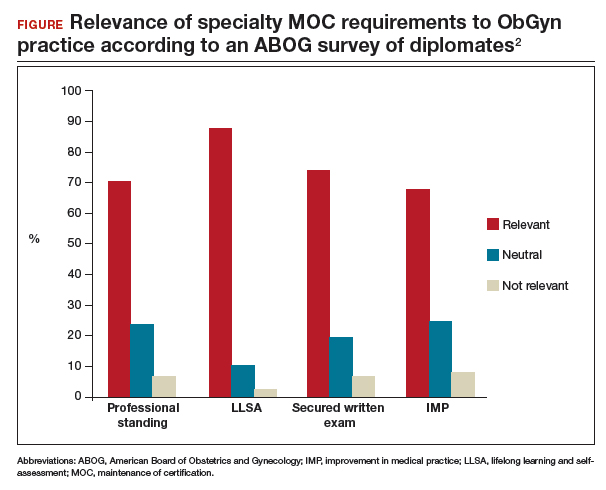

- providing Lifelong Learning and Self-Assessment (LLSA) articles that, according to 90% of diplomates surveyed, are beneficial to their clinical practice (FIGURE).1,2

Our colleague physicians are not so lucky. In a 2015 New England Journal of Medicine Perspective, one physician called out the American Board of Internal Medicine as “a private, self-appointed certifying organization,” a not-for-profit organization that has “grown into a $55-million-per-year business.”3 He concluded that “many physicians are waking up to the fact that our profession is increasingly controlled by people not directly involved in patient care who have lost contact with the realities of day-to-day clinical practice.”3

State and society responses to MOC requirements

Frustration with an inability to resolve these concerns has grown steadily, bubbling over into state governments. The American Medical Association developed “model state legislation intended to prohibit hospitals, health care insurers, and state boards of medicine and osteopathic medicine from requiring participation in MOC processes as a condition of credentialing, privileging, insurance panel participation, licensure, or licensure renewal.”4

Some states are proposing or have enacted legislation that prohibits the use of MOC as a criterion for licensure, privileging, employment, reimbursement, and/or insurance panel participation. Eight states (Arizona, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Maine, Missouri, Oklahoma, Tennessee) have enacted laws to prohibit the use of MOC for initial and renewal licensure decisions. Many states are actively considering MOC-related legislation, including Alaska, Florida, Iowa, Indiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, New Hampshire, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Utah, Washington, and Wisconsin.

Legislation is not the only outlet for physician frustration. Some medical specialty societies are considering dropping board certification as a membership requirement; physicians are exploring developing alternative boards; and some physicians are defying the board certification requirement altogether, with thousands signing anti-MOC petitions.

ACOG asserts importance of maintaining self-regulation

While other specialties are actively advocating state legislation, ACOG and ABOG have worked together to oppose state legislation, believing that physician self-regulation is paramount. In fact, in 2017, ACOG and ABOG issued a joint statement urging state lawmakers to “not interfere with our decades of successful self-regulation and to realize that each medical society has its own experience with its MOC program.”5