Routine laboratory evaluation

Testing should comprise a chemistry panel to evaluate serum creatinine, electrolytes, and liver enzymes. A 24-hour urine collection for protein excretion and creatinine clearance or a urine protein–creatinine ratio should be obtained to record baseline kidney function.4 (Such testing is important, given that new-onset or worsening proteinuria is a manifestation of superimposed preeclampsia.) All pregnant patients with chronic hypertension also should have a complete blood count, including a platelet count, and an early screen for gestational diabetes.

Depending on what information is obtained from the history and physical examination, renal ultrasonography and any of several laboratory tests can be ordered, including thyroid function, an SLE panel, and vanillylmandelic acid/metanephrines. If the patient has a history of severe hypertension for greater than 5 years, is older than 40 years, or has cardiac symptoms, baseline electrocardio-graphy or echocardiography, or both, are recommended.

Clinical manifestations of chronic hypertension during pregnancy include5:

- in the mother: accelerated hypertension, with resulting target-organ damage involving heart, brain, and kidneys

- in the fetus: placental abruption, preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, and fetal death.

What should treatment seek to accomplish?

The goal of antihypertensive medication during pregnancy is to reduce maternal risk of stroke, congestive heart failure, renal failure, and severe hypertension. No convincing evidence exists that antihypertensive medications decrease the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia, preterm birth, placental abruption, or perinatal death.

According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), antihypertensive medication is not indicated in patients with uncomplicated chronic hypertension unless systolic BP is ≥ 160 mm Hg or diastolic BP is ≥ 105 mm Hg.3 The goal is to maintain systolic BP at 120–160 mm Hg and diastolic BP at 80–105 mm Hg. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends treatment of hypertension when systolic BP is ≥ 150 mm Hg or diastolic BP is ≥ 100 mm Hg.6 In patients with end-organ disease (chronic renal or cardiac disease) ACOG recommends treatment with an antihypertensive when systolic BP is >140 mm Hg or diastolic BP is >90 mm Hg.

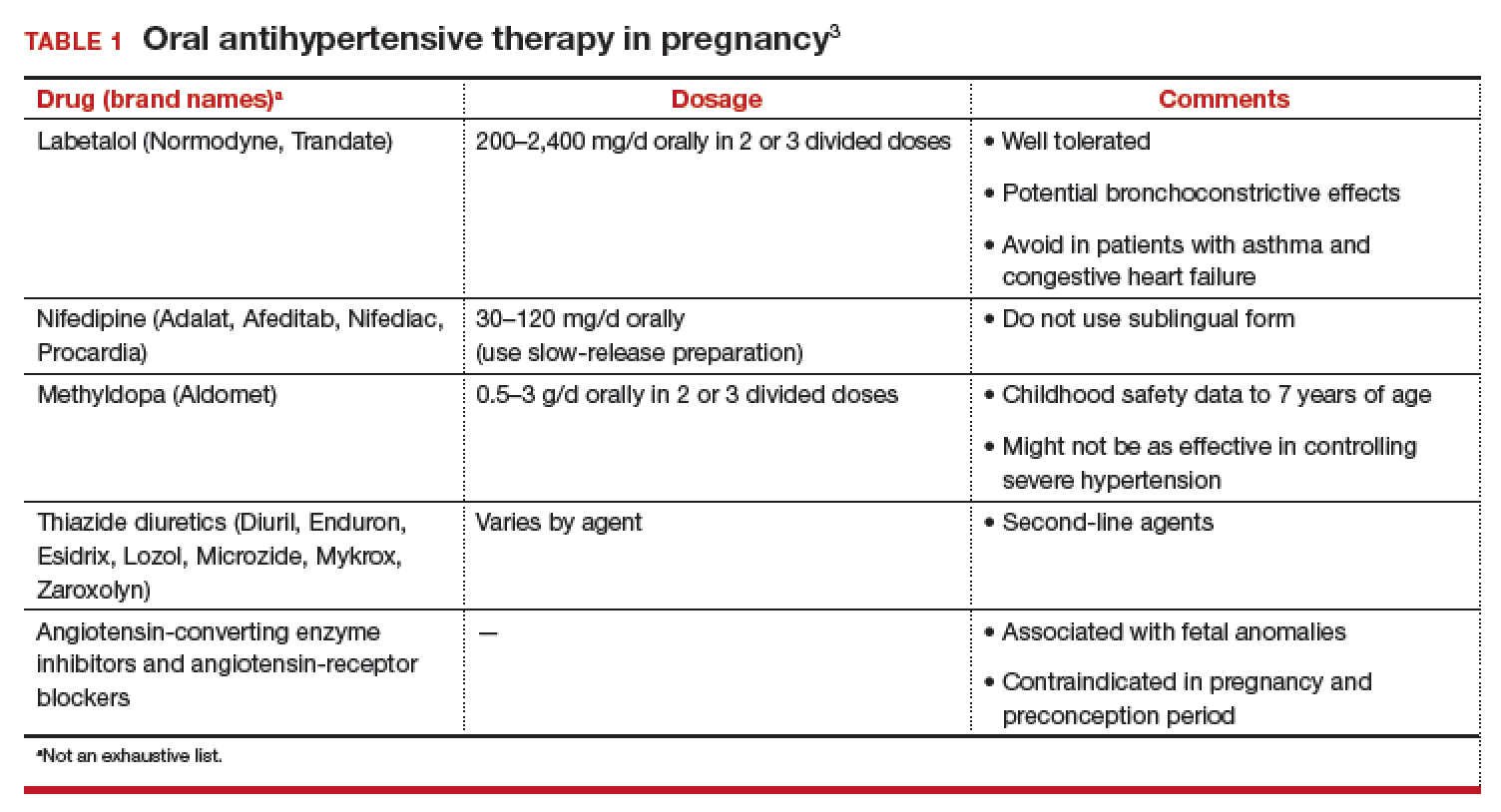

First-line antihypertensives consideredsafe during pregnancy are methyldopa, labetalol, and nifedipine. Thiazide diuretics, although considered second-line agents, may be used during pregnancy—especially if BP is adequately controlled prior to pregnancy. Again, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers are contraindicated during pregnancy (TABLE 1).3

Continuing care in chronic hypertension

Given the maternal and fetal consequences of chronic hypertension, it is recommended that a hypertensive patient be followed closely as an outpatient; in fact, it is advisablethat she check her BP at least twice daily. Beginning at 24 weeks of gestation, serial ultrasonography should be performed every 4 to 6 weeks to evaluate interval fetal growth. Twice-weekly antepartum testing should begin at 32 to 34 weeks of gestation.

During the course of the pregnancy, the chronically hypertensive patient should be observed closely for development of superimposed preeclampsia. If she does not develop preeclampsia or fetal growth restriction, and has no other pregnancy complications that necessitate early delivery, 3 recommendations regarding timing of delivery apply7:

- If the patient is not taking antihypertensive medication, delivery should occur at 38 to 39 6/7 weeks of gestation

- If hypertension is controlled with medication, delivery is recommended at 37 to 39 6/7 weeks of gestation.

- If the patient has severe hypertension that is difficult to control, delivery might be advisable as early as 36 weeks of gestation.

Be vigilant for maternal complications (including cardiac compromise, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, hypertensive encephalopathy, and worsening renal disease) and fetal complications (such as placental abruption, fetal growth restriction, and fetal death). If any of these occur, management must be tailored and individualized accordingly. Study results have demonstrated that superimposed preeclampsia occurs in 20% to 30% of patients who have underlying mild chronic hypertension. This increases to 50% in women with underlying severe hypertension.8

Antihypertensive medication is the mainstay of treatment for severely elevated blood pressure (BP). To avoid fetal heart rate decelerations and possible emergent cesarean delivery, however, do not decrease BP too quickly or lower to values that might compromise perfusion to the fetus. The BP goal should be 140-155 mm Hg (systolic) and 90-105 mm Hg (diastolic). A

Be prepared for eclampsia, which is unpredictable and can occur in patients without symptoms or severely elevated BP and even postpartum in patients in whom the diagnosis of preeclampsia was never made prior to delivery. The response to eclamptic seizure includes administering magnesium sulfate, which is the approved initial therapy for an eclamptic seizure. A

Make algorithms for acute treatment of severe hypertension and eclampsia readily available or posted in labor and delivery units and in the emergency department. C

Counsel high-risk patients about the potential benefit of low-dosage aspirin to prevent preeclampsia. A

Strength of recommendation:

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series