The consent of minor patients

The traditional legal rule is that parents or guardians (“parent” refers to both) must consent to medical treatment for minor children. There is an exception for emergency situations but generally minors do not provide consent for medical care, a parent does.1 The parent typically is obliged to provide payment (often through insurance) for those services.

This traditional rule has some exceptions—the emergency exception already noted and the case of emancipated minors, notably an adolescent who is living almost entirely independent of her parents (for example, she is married or not relying on parents in a meaningful way). In recent times there has been increasing authority for “mature minors” to make some medical decisions.2 A mature minor is one who has sufficient understanding and judgment to appreciate the consequences, benefits, and risks of accepting proposed medical intervention.

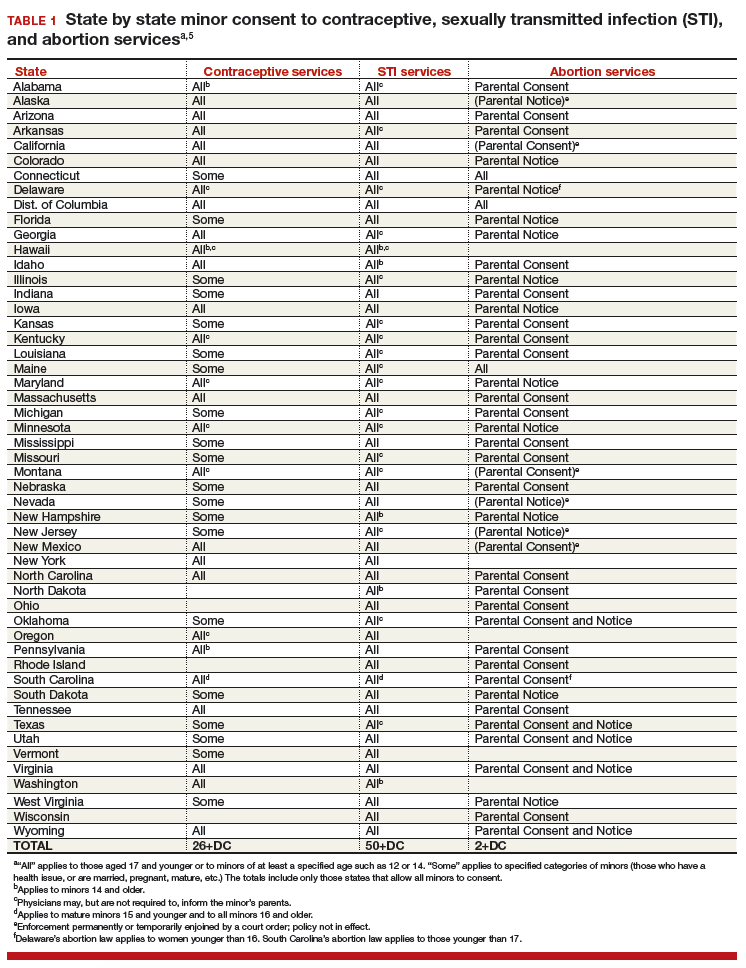

No circumstance involving adolescent treatment has been more contentious than services related to abortion and, to a lesser degree, contraception.3 Both the law of consent to services and the rights of parents to obtain information about contraceptive and abortion services have been a matter of strong, continuing debate. The law in these areas varies greatly from state-to-state, and includes a mix of state law (statutes and court decisions) with an overlay of federal constitutional law related to reproduction-related decisions of adolescents. In addition, the law in this area of consent and information changes relatively frequently.4 Clinicians, of course, must focus on the consent laws of the state in which they practice.

STI counseling and treatment

All states permit a minor patient to consent to treatment for an STI (TABLE 1).5 A number of states expressly permit, but do not require, health care providers to inform parents of treatment when a physician determines it would be in the best interest of the minor. Thus, the clinic would not be required to provide proactively the information to our case patient’s mother (regarding any STI issues) when she called.6

Contraception

Consent for contraception is more complicated. About half the states allow minors who have reached a certain age (12, 14, or 16 years) to consent to contraception. About 20 other states allow some minors to consent to contraceptive services, but the “allowed group” may be fairly narrow (eg, be married, have a health issue, or be “mature”). In 4 states there is currently no clear legal authority to provide contraceptive services to minors, yet those states do not specifically prohibit it. The US Supreme Court has held that a state cannot completely prohibit the availability of contraception to minors.7 The reach of that decision, however, is not clear and may not extend beyond what the states currently permit.

The ability of minors to consent to contraception services does not mean that there is a right to consent to all contraceptive options. As contraception becomes more irreversible, permanent, or risky, it is more problematic. For example, consent to sterilization would not ordinarily be within a minor’s recognized ability to consent. Standard, low risk, reversible contraception generally is covered by these state laws.8

In our case here, the patient likely was able to consent to contraception—initially to the oral contraception and later to the IUD. The risks and reversibility of both are probably within her ability to consent.9,10 Of course, if the care was provided in a state that does not include the patient within the groups that can give consent to contraception, it is possible that she might not have the legal authority to consent.

Continue to: General requirements of consent...