Postpartum blood loss greater than 1,000 mL occurs in approximately 7% of cesarean delivery (CD) procedures with the administration of oxytocin alone or oxytocin plus misoprostol.1 Rapid identification and control of hemorrhage is essential to avoid escalating coagulopathy and maternal instability. In cases of excess blood loss, clinicians request assistance from colleagues, endeavor to identify the cause of the bleeding, utilize additional uterotonics (methylergonovine, carboprost, misoprostol), perform uterine massage, warm the uterus, repair lacerations and replace blood products. If blood loss continues after these initial measures, obstetricians may consider uterine artery embolization (UAE) or hysterectomy. While UAE is a highly effective measure to control postpartum hemorrhage, it is not available at all obstetric hospitals. Even when available, there may be a significant time delay from the decision to consult an interventional radiologist to completion of the embolization procedure.

To avoid the permanent sterilization of a hysterectomy, or to obtain time for UAE or correction of coagulopathy, additional uterus-sparing surgical interventions should be considered. These include: 1) progressive uterine devascularization, 2) uterine compression sutures, and 3) intrauterine balloon tamponade. One caveat is that there is very little high-quality evidence from randomized trials to compare the efficacy or outcome of these uterine-sparing surgical interventions. Most of our evidence is based on limited case series and expert recommendations.

Uterine devascularization

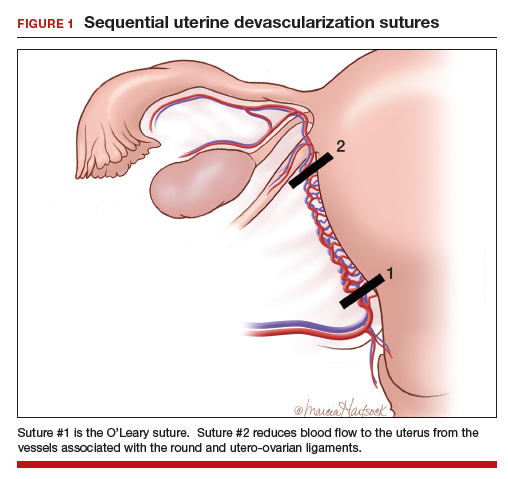

Many techniques have been described for performing progressive uterine devascularization. Most experts recommend first performing an O’Leary suture, ligating both ascending uterine arteries and accompanying veins at a point approximately 2 cm closer to the cervix than the uterine incision (FIGURE 1). An absorbable suture is passed through the myometrium, being sure to remain medial to the ascending uterine vessels. Clear visualization of the vessels posteriorly is essential, usually necessitating exteriorization of the uterus. The needle is then driven through an avascular space in the broad ligament close to the uterine vessels, and the suture is tied down. Ureteral injury can be avoided by extending the bladder flap laterally to the level of the round ligament and mobilizing the vesicouterine peritoneum inferiorly, with the suture placed directly on endopelvic fascia. If necessary, the utero-ovarian ligament can be ligated in a second step, just below the uterine-tubal junction. The progressive devascularization intervention can be limited to the first or second steps if bleeding is well controlled.

In our experience, bilateral O’Leary sutures are highly effective at controlling ongoing uterine bleeding, particularly from the lower uterine segment. In the event that they are not successful, placement does not preclude later use of UAE.

Uterine compression sutures

Compression sutures are most often used in the setting of refractory uterine atony. They also may be helpful for controlling focal atony or bleeding from a placental implantation site. More than a dozen different types of uterine compression sutures have been reported in the literature; the B-Lynch, Hyman, and Pereira sutures are most commonly performed.2

Continue to: The B-Lynch suture3 is performed with...