Intact removal of an ovarian cyst is a well-established gynecologic surgical principle because ovarian cancer is definitively diagnosed only in retrospect (after ovarian extraction) and intraoperative cyst rupture upstages an otherwise nonmetastatic cancer to stage IC. This lumps cancers that are ruptured during surgical extraction together with those that have spontaneously ruptured or have surface excrescences. The theoretical rationale for this “lumping” is that contact between malignant cells from the ruptured cyst may take hold on peritoneal surfaces resulting in development of metastases. To offset this theoretical risk, it has been recommended that all stage IC ovarian cancer is treated with chemotherapy, whereas low-grade stage IA and IB cancers generally are not. No conscientious surgeon wants their surgical intervention to be the cause of a patient needing toxic chemotherapy. But is the contact between malignant cyst fluid and the peritoneum truly as bad as a spontaneous breach of the surface of the tumor? Or is cyst rupture a confounder for other adverse prognostic features, such as histologic cell type and dense pelvic attachments? If ovarian cyst rupture is an independent risk factor for patients with stage I ovarian cancer, strategies should be employed to avoid this occurrence, and we should understand how to counsel and treat patients in whom this has occurred.

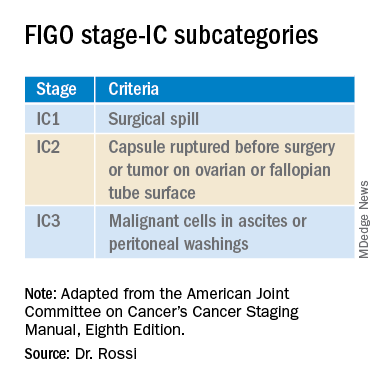

In 2017 the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging of epithelial ovarian cancer subcategorized stage IC. This group encompasses women with contact between malignant cells and the peritoneum in the absence of other extraovarian disease. The table includes these distinct groupings. Stage IC1 includes patients in whom intraoperative spill occurred. Stage IC2 includes women with preoperative cyst rupture, and or microscopic or macroscopic surface involvement because the data support that these cases carry a poorer prognosis, compared with those with intraoperative rupture (IC1).1 The final subcategory, IC3, includes women who have washings (obtained at the onset of surgery, prior to manipulation of the tumor) that were positive for malignant cells, denoting preexisting contact between the tumor and peritoneum and a phenotypically more aggressive tumor.

The clinical significance of ovarian cancer capsule rupture has been evaluated in multiple studies with some mixed results.1 Consistently, it is reported that preoperative rupture, surface or capsular involvement, and preexisting peritoneal circulation of metastatic cells all portend a poorer prognosis; however, it is less clear that iatrogenic surgical rupture has the same deleterious association. In a large retrospective series from Japan, the authors evaluated 15,163 cases of stage I ovarian cancer and identified 7,227 cases of iatrogenic (intraoperative) cyst rupture.2 These cases were significantly more likely to occur among clear cell cancers, and were more likely to occur in younger patients. Worse prognosis was associated with cell type (clear cell cancers), but non–clear cell cancers (such as serous, mucinous, and endometrioid) did not have a higher hazard ratio for death when intraoperative rupture occurred. But why would intraoperative cyst rupture result in worse prognosis for only one histologic cell type? The authors hypothesized that perhaps rupture was more likely to occur during extraction of these clear cell tumors because they were associated with dense adhesions from associated endometriosis, and perhaps an adverse biologic phenomenon associated with infiltrative endometriosis is driving the behavior of this cancer.

The Japanese study also looked at the effect of chemotherapy on these same patients’ outcomes. Interestingly, the addition of chemotherapy did not improve survival for the patients with stage IC1 cancers, which was in contrast to the improved survival seen when chemotherapy was given to those with spontaneous rupture or ovarian surface involvement (IC2, IC3). These data support differentiating the subgroups of stage IC cancer in treatment decision-making, and suggest that adjuvant chemotherapy might be avoided for patients with nonclear cell stage IC1 ovarian cancer. While the outcomes are worse for patients with ruptured clear cell cancers, current therapeutic options for clear cell cancers are limited because of their known resistance to traditional agents, and outcomes for women with clear cell cancer can be worse across all stages.

While cyst rupture may not always negatively affect prognosis, the goal of surgery remains an intact removal, which influences decisions regarding surgical approach. Most adnexal masses are removed via minimally invasive surgery (MIS). MIS is associated with benefits of morbidity and cost, and therefore should be considered wherever feasible. However, MIS is associated with an increased risk of ovarian cyst rupture, likely because of the rigid instrumentation used when approaching a curved structure, in addition to the disparity in size of the pathology, compared with the extraction site incision.3 When weighing the benefits and risks of different surgical approaches, it is important to gauge the probability of malignancy. Not all complex ovarian masses associated with elevations in tumor markers are malignant, and certainly most that are associated with normal tumor markers are not. If the preoperative clinical data suggest that the mass is more likely to be malignant (e.g., mostly solid, vascular tumors with very elevated tumor markers), consideration might be made to abandoning a purely minimally invasive approach to a hand-assisted MIS or laparotomy approach. However, it would seem that abandoning an MIS approach to remove every ovarian cyst is unwise given that there is clear patient benefit with MIS and, as discussed above, most cases of iatrogenic malignant cyst rupture are unavoidable even with laparotomy, and do not necessarily independently portend poorer survival or mandate chemotherapy.

Surgeons should be both nuanced and flexible and apply some basic rules of thumb when approaching the diagnostically uncertain adnexal mass. Peritoneal washings should be obtained at the commencement of the case to discriminate those cases of true stage IC3. The peritoneum parallel to the ovarian vessel should be extensively opened to a level above the pelvic brim. In order to do this, the physiological attachments between the sigmoid colon or cecum and the suspensory ligament of the ovary may need to be carefully mobilized. This allows for retroperitoneal identification of the ureter and skeletonization of the ovarian vessels at least 2 cm proximal to their insertion into the ovary and avoidance of contact with the ovary itself (which may have a fragile capsule) or incomplete ovarian resection. If the ovary remains invested close to the sidewall or colonic structures and the appropriate peritoneal and retroperitoneal mobilization has not occurred, the surgeon may unavoidably rupture the ovarian cyst as they try to “hug” the ovary with their bites of tissue in an attempt to avoid visceral injury. There is little role for an ovarian cystectomy in a postmenopausal woman undergoing surgery for a complex adnexal mass, particularly if she has elevated tumor markers, because the process of performing ovarian cystectomy commonly invokes cyst rupture or fragmentation. Ovarian cystectomy should be reserved for premenopausal women with adnexal masses at low suspicion for malignancy. If the adnexa appears densely adherent to adjacent structures – for example, associated with infiltrative endometriosis – consideration for laparotomy or a hand-assisted approach may be necessary; in such cases, even open surgery can result in cyst rupture, and the morbidity of conversion to laparotomy should be weighed for individual cases.

Finally, retrieval of the ovarian specimen should occur intact without morcellation. There should be no uncontained morcellation of adnexal structures during retrieval of even normal-appearing ovaries. The preferred retrieval method is to place the adnexa in an appropriately sized retrieval bag, after which contained morcellation or drainage can occur to facilitate removal through a laparoscopic incision. Contained morcellation is very difficult for large solid masses through a laparoscopic port site; in these cases, extension of the incision may be necessary.

While operative spill of an ovarian cancer does upstage nonmetastatic ovarian cancer, it is unclear that, in most cases, this is independently associated with worse prognosis, and chemotherapy may not always be of added value. However, best surgical practice should always include strategies to minimize the chance of rupture when approaching adnexal masses, particularly those at highest likelihood of malignancy.

References

1. Kim HS et al. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013 Mar 39(3):279-89.

2. Matsuo K et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Nov;134(5):1017-26.

3. Matsuo K et al. JAMA Oncol. 2020 Jul 1;6(7):1110-3.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.