More adults are walking these days, but many are still not walking long enough, far enough, or frequently enough to improve their health, according to a new government report.

In 2010, 62% of American adults who responded to the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) reported at least one 10-minute walk in the previous week, compared with 56% of those surveyed in 2005. Despite the relative improvement, reported in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Aug. 7 issue of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, fewer than half of the adults surveyed meet the minimum recommended amount of physical activity, Dr. Thomas R. Frieden, CDC director, said in a press telebriefing announcing the findings.

Specifically, to attain the health benefits associated with physical fitness, adults require a minimum of 150 minutes per week of moderate aerobic physical activity, achieved no less than 10 minutes at a time, according to the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. So, while the jump in the number of adults who report walking for fun, transportation, or exercise is "encouraging," according to Joan M. Dorn, Ph.D., of the CDC’s Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity, "there is still much room for improvement."

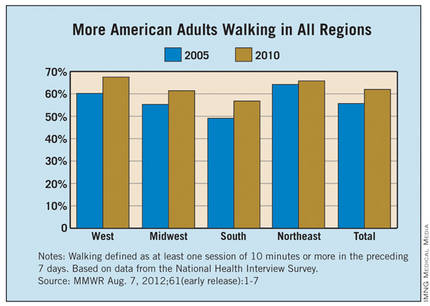

The report noted an increase in walking in nearly all of the groups surveyed, with the greatest increase – from 49% in 2005 to 57% in 2010 – among adults in the South. The smallest increase – 1.6% – was observed in the Northeast, but 66% of adults in that region are walkers, which is the second highest regional rate. The respective rate increases in the Midwest and West regions of the country were 6.1% and 7.3%, with approximately 61% and 68% of adults living in those regions reporting at least 10 minutes of walking per week (MMWR 2012 Aug. 7 [61]:1-7).

Approximately 62% of both men and women reported being walkers in 2010, compared with approximately 54% and 57%, respectively, in 2005. When evaluated by age and body mass index, respectively, the greatest rate increases were seen among 25- to 34-year-olds (9.3%) and overweight adults (7.2%), while the smallest increases were observed in adults aged 65 years or older (3.6%) and those classified as obese (5.8%). Curiously, although the percentage of adult walkers increased, even among subgroups at risk for inactivity, such as those with lower educational attainment (the percentage point change among non–high school graduates was 4.2%), according to the authors, "average walking time among those who walked at least 10 minutes in the preceding 7 days decreased by about 2 minutes per day." The reason for the decrease is unknown, they wrote.

Although only 48% of adults surveyed in 2010 met the aerobic activity recommendation, that rate is nearly six percentage points higher than in 2005, according to the report. Not surprisingly, according to Dr. Dorn, "the percentage of adults who meet the physical activity requirements is higher among walkers than nonwalkers." Specifically, in 2010, 59.5% of those who walked met the guideline, compared with 29.5% of those who did not, and walkers were significantly more likely to meet the guideline than were nonwalkers across every subgroup examined, even among adults requiring walking assistance and those with chronic diseases such as arthritis, hypertension, and diabetes.

The public health implications of the findings are substantial, Dr. Frieden stressed, referring to the association between physical activity and heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, depression, and some cancers. They also point to the need for environmental and policy efforts aimed at getting people walking – an easily achievable physical activity for most people that doesn’t require special skills or facilities, he said.

Specific strategies from the Guide to Community Preventive Services that can be used to promote walking include increasing access to places for physical activity, informational outreach, and urban design and land-use policies developed with an eye toward walker friendliness. "People need more safe and convenient places to walk," Dr. Dorn said in a press statement. "People walk more where they feel protected from traffic and safe from crime. Communities can be designed or improved to make it easier for people to walk to the places the need and want to go."