- Untreated, atypical endometrial hyperplasia progresses to adenocarcinoma in 23% of patients, persists as hyperplasia in 19%, and regresses in 58%.

- A review of 4 large studies found that progestin was associated with regression in 90% of women with hyperplasia arising from unopposed estrogen therapy. Several small retrospective studies found that progestin was likely to induce regression of atypical hyperplasia unrelated to estrogen therapy.

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues appear to be effective for hyperplasia without atypia.

Although many gynecologists proceed to hysterectomy when hyperplasia with cellular atypia is found on an endometrial biopsy or curettage specimen, a number of conservative therapies are particularly useful for younger patients who wish to preserve fertility, and for women who do not desire or cannot undergo hysterectomy.

Prevalence and risk factors

Endometrial hyperplasia is a precursor to endometrial carcinoma, the most common malignancy of the female reproductive tract. In 2003, endometrial cancer is expected to account for approximately 6% of new female cancer cases and 3% of female cancer deaths.1

Besides endometrial hyperplasia, prominent risk factors for carcinoma are unopposed estrogen therapy, obesity, diabetes, early menarche, and late menopause.2

Classifying endometrial hyperplasia

In 1985, Kurman et al3 clarified the classification system for endometrial hyperplasia, proposing 2 broad categories: simple and complex (TABLE 1).

Simple hyperplasia is characterized by benign proliferation of endometrial glands, which are irregular and perhaps dilated, but which lack back-to-back crowding or cellular atypia (FIGURE 1).

Complex hyperplasia is characterized by grossly irregular endometrium and abnormal vasculature. It exhibits proliferation of endometrial glands with irregular outlines, architectural complexity, and back-to-back crowding but no atypia.

Presence or absence of atypia characterizes subdivisions of these 2 categories by degree of nuclear atypia and loss of polarity. Atypia can be found in both complex (FIGURE 2) and simple hyperplastic lesions.

TABLE 1

Classification of endometrial hyperplasia

| CLASSIFICATION | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Simple | Benign proliferation of endometrial glands that are irregular and perhaps dilated but do not display back-to-back crowding or cellular atypia |

| Complex | Proliferation of endometrial glands with irregular outlines, architectural complexity, and back-to-back crowding but no atypia |

| Atypical | Varying degrees of nuclear atypia and loss of polarity. Found in both simple and complex hyperplastic lesions |

| Data from: Kurman et al3 | |

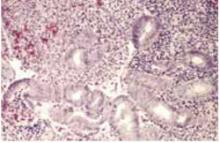

FIGURE 1 Simple hyperplasia without atypia

Simple hyperplasia with irregular glands but no back-to-back crowding or cellular atypia (hematoxylin & eosin×100).

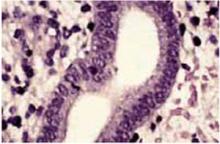

High-power magnification of simple hyperplasia without atypia. The nuclei are uniform without cellular atypia (hematoxylin & eosin×400).

A majority of hyperplastic lesions regress

In their sentinel article on the classification of endometrial hyperplasia, Kurman et al3 describe the behavior of the 4 categories of endometrial hyperplasia in 170 patients (TABLE 2). They found that, during a mean follow-up of 11.4 years, disease regressed in 69% of patients with simple atypical hyperplasia, 57% of patients with complex atypical hyperplasia, and 58% of patients with hyperplasia with cellular atypia.

Disease progressed to carcinoma in 8% of patients with simple atypical hyperplasia, 29% of patients with complex atypical hyperplasia, and 23% of patients with hyperplasia with cellular atypia.

One patient with disease progression had stage IV endometrial carcinoma with metastasis to the inguinal lymph nodes and bowel.3

The average age for patients with atypia was 40; 38% of patients were 35 or younger.

In a similar study involving 77 women with hyperplasia, 79% of cases with simple hyperplasia regressed over the 3 years of follow-up, as did the 1 case (100%) of simple hyperplasia with atypia, 94% of cases with complex hyperplasia, and 55% of cases with complex hyperplasia with atypia. Only 1 patient experienced progression to endometrial carcinoma; she initially had complex atypical hyperplasia.4

With proper monitoring, oral progestin therapy is a reasonable alternative to hysterectomy for treatment of hyperplasia.

TABLE 2

Regression, persistence, and progression rates of endometrial hyperplasia

| TYPE | N | %REGRESSION | % PERSISTENCE | % PROGRESSION |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple | 93 | 80 | 19 | 1 |

| Simple with atypia | 13 | 69 | 23 | 8 |

| Complex | 29 | 80 | 17 | 3 |

| Complex with atypia | 35 | 57 | 14 | 29 |

| All lesions with atypia | 48 | 58 | 19 | 23 |

| Source: Kurman RJ, et al. Cancer. 1985;56:403-412. Copyright ©2003 American Cancer Society. Reprinted by permission of Wiley-Liss, Inc, a subsidiary of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. | ||||

Progestin therapy enhances regression

Because endometrial hyperplasia is estrogendependent, progestins are often used to induce regression. Progestin appears to decrease glandular cellularity in these lesions by triggering apoptosis.5 In addition, medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) significantly inhibits angiogenesis in the myometrium immediately underlying complex endometrial hyperplasia.6

Oral administration.

- Simple or complex hyperplasia associated with estrogen therapy. A recent review of 4 large trials suggests that hyperplasia induced by estrogen therapy responds well to progestin treatment regardless of whether the disease is simple or complex. In the 4 trials, estrogen was discontinued and MPA was given continuously for 6 weeks or cyclically for 3 months.7 Both regimens were effective, with a total regression rate of 90% for all 4 studies.

- Atypical hyperplasia unrelated to estrogen therapy. Several small retrospective studies demonstrated a beneficial effect of progestin treatment of atypical hyperplasia unrelated to estrogen therapy.