Wide range of BMIs

In the study by Narendran and Baggish, successful measurement panels were created for 99 of the 101 cases. Of these, 49 women had a BMI of less than 25 (normal), 29 had a BMI greater than 25 but less than 30 (overweight), and 21 had a BMI greater than 30 (obese).

A significant difference was observed in the perpendicular distance from the entry trocar to aortic bifurcation (TABLE 1). Specifically, as the BMI increased, so did the distance. The only other significant BMI-related increase was the abdominal wall thickness, which also varied directly with the BMI.

Other distances increase with height

The distance between the primary trocar and the iliac vessels and urinary bladder consistently increased with the patient’s height.

However, no significant change in distance between the great vessels and the primary trocar site occurred when the patient’s position changed from level to Trendelenburg.

Trocar insertion: Disposable devices require less force

Laparoscopic trocar thrusting is a dynamic process, and we observed that process in our study.15 When force is applied via trocar to the anterior abdominal wall, that structure is displaced toward the abdominal cavity in the direction of the posterior abdominal wall—even when countertraction is taken into consideration. The movement is more apparent in obese women because of greater elasticity created by the larger mass of properitoneal and subcutaneous fat. We measured the distortion and determined that the depression can be 5 cm or more.

In contrast, thin women have rigid, relatively unyielding anterior abdominal walls and therefore experience minimal displacement. In thin women, the greater risk is the shorter passive distance between the anterior abdominal wall and the great vessels.

Comparing force curves

We16 calculated the force required to thrust a disposable or reusable trocar through the anterior abdominal wall during actual laparoscopic surgery. We used a 25-lb compression load cell connected to the trocar by an Ultem handle, which could be sterilized between cases. A linear variable displacement transducer detected displacement, and the measuring apparata fed data into a computer. Ten women were randomized to a disposable trocar and 10 to a reusable device.

The mean thrusting force for disposable trocars was 10.2 lb versus 17.53 lb for the reusable device. The time to penetrate was likewise significantly shortened for disposable trocars: mean time of 3.54 seconds versus 11.64 seconds. Overall work tilted in favor of disposable trocars: 14.34 pound-seconds versus 103.88 pound-seconds.

The disposable trocar has the advantage for 2 reasons: its razor-sharp cutting edge and streamlined design.

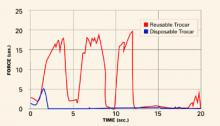

FIGURE 1 shows typical force curves of disposable and reusable trocars.

FIGURE 1 Reusable trocar requires more force than disposable trocar

A considerable difference in force is required for insertion, depending on type of device, as this graph of typical force curves shows. The reusable trocar requires 18 to 20 lb of force over 12 seconds; the disposable, only 5 lb over 2 seconds.

Safe trocar insertion begins with pneumoperitoneum

McDougall et al17 demonstrated that adequate pneumoperitoneum lessens the force required to drive a trocar through the anterior abdominal wall. Although the differences were small, the forces required with an intraperitoneal gas pressure of 30 mm Hg were smaller than those required with a pressure of 15 mm Hg.17

Manufacturers of disposable trocars also recommend creating an adequate pneumoperitoneum prior to aiming and inserting the razor-sharp device. The goal is creating a carbon dioxide gas pocket large enough to permit rapid deployment of the “safety shield” after the trocar tip clears the properitoneal fat and peritoneal membrane.

Slow-motion video sequences of disposable trocar entry show the sharp trocar tip penetrating the parietal peritoneum of the anterior abdominal wall for 1 cm before the spring-loaded shield advances and locks over the blade. During this insertion, the anterior abdominal wall has an elastic reaction to the applied force; this reaction pushes it toward the posterior abdominal wall.

Direct insertions (ie, without adequate pneumoperitoneum) involve less space for the trocar’s safety shield to deploy. Thus, there is a greater risk of the armed trocar tip coming into direct contact with underlying viscera and blood vessels.

Delayed diagnosis

The earlier a major vessel incident can be diagnosed, the better for patient, physician, and hospital. Diagnosis after the onset of hypotension, tachycardia, or tachypnia constitutes “late” diagnosis. Dark venous blood pooling in the abdomen, bright red pulsatile blood emitting from a trocar sleeve, or a retroperitoneal hematoma lateral to the iliacs or at the level of the presacral space suggests major vessel injury. Signs of hypovolemic shock or sudden appearance of profound shock places the possibility of major vessel injury at the top of the differential diagnosis.

Relying on observation when a retroperitoneal hematoma develops

Unfortunately, with observation, the surgeon cannot determine the identity or nature of the damaged vessel, know whether the hematoma is expanding beyond the view of the laparoscope, or predict when the patient will go into shock.

Leaving an armed trocar in place in a vessel

Assuming that the trocar is plugging a hole and preventing hemorrhage is a recipe for disaster. The movement of the sharp device against a vessel wall is most likely to create greater trauma to the vessel. In the case of partial penetration, the device may cut the rest of the way through the vessel.

Laparoscopic exploration

Attempts to locate the injury via laparoscopy usually are unsuccessful, and laparoscopic attempts to sew up the injury limit accuracy and efficacy.

Use of the Pfannenstiel incision during emergency laparotomy

Unfortunately, in 1 study,13 27 of 31 women with vascular injuries received this incision. A vertical incision is preferred because it affords greater access and visibility.

Underestimating blood loss

In the case of a major vessel injury, underestimation of blood volume requirements can be fatal. In 1 study,13 19 of 31 women were under-transfused and/or inadequately cross-matched.

Clamping injured vessels

This can lead to arterial or venous thrombosis. Nonvascular clamps can tear large vessels, adding to the damage and complicating the vascular surgeon’s attempt at repair. Rather, apply direct pressure with a sponge stick.

Delay in calling for help

This translates into greater blood loss and a less stable patient. In 1 study,13 the mean time for a vascular surgeon to intercede was 23 minutes.