FIGURE 11 Postoperative appearance of endometriosis resection

As dissection proceeds medially, use the perirectal fatty plane to remove implants between the uterosacral area and rectum. In the midline, remove implants below the rectosigmoid peritoneal reflexion, taking care not to injure the rectum.

Implants above the peritoneal reflexion are often attached to the sigmoid tinea coli and cannot be removed without taking a portion of the bowel. Thus, patients with extensive endometriosis should have a bowel prep with two 10-ounce bottles of magnesium citrate the day before surgery.

If bowel resection is necessary, consult a general surgeon or gynecologic oncologist. A history of painful defecation or a finding of nodules in the cul-de-sac with rectal dimpling warrants preoperative consultation with a specialist skilled at bowel resection.

Ureteral injuries occur in 0.5% to 2.5% of women undergoing gynecologic surgery.1 The most common predisposing condition is previous pelvic surgery.2,3 The usual sites of injury are at the pelvic rim close to the ovarian vessels, at the level of the uterine artery, and lateral to the vaginal cuff. Neither preoperative excretory urograms nor placement of ureteral catheters preoperatively have been found to be effective prevention measures.2,4-6 Using the steps described above, the ureter can be identified and mobilized.

Blood supply to the ureter comes from the plexus of vessels that form a network along the length of the ureter. This plexus is fed by arteries from the renal pelvis, common iliac, internal iliac, uterine artery, and the base of the bladder. Complete mobilization of the ureter away from its peritoneal attachments and these lateral blood supply sources can be accomplished as long as the vascular plexus is not disrupted by cautery, crushing, or tearing. A clean transection can be re-anastomosed or reimplanted with the expectation of normal healing. Innervation of the ureter is from the inferior mesenteric plexus superiorly and the inferior hypogastric plexus in the pelvis. Ureteral peristalsis will continue, even if the ureter is completely divided or ligated.

Protecting pelvic blood vessels

The majority of gynecologic operations involve the ovarian vessels and the uterine vessels. The operator rarely needs to explore the lateral pelvis to identify the rest of the vessels. When faced with a large endometrioma or cancer, knowledge of the anatomy of the lateral blood vessels is vital.

Since the pathology is usually deeper in the pelvis, it is wise to identify the anatomy of the pelvis starting at the pelvic brim, where the common iliac bifurcates into the external and internal iliacs. There is a safe dissection plane medial to the internal iliac artery all the way to the uterine artery. This exposes the pararectal space, which can be opened without risk of major bleeding (FIGURE 5).

The obliterated umbilical vessel is the other friendly marker just distal to the uterine artery. It can be placed on traction and the uterine artery isolated. The inferior and superior vesical arteries are generally not dissected, as they are adjacent to the bladder and the surgery takes place medial to them in the prevesical fascial space.

Hypogastric artery ligations are rarely performed today, as interventional radiology is the standard of care for patients with postoperative and postpartum bleeding. When it becomes necessary, the hypogastric artery can be isolated and tied using the right-angle clamp to pass the tie. The superior gluteal artery branches so close to the bifurcation of the common iliac artery that it is not visualized. The inferior gluteal artery is the largest distal branch, which might be visualized during the ligation. It is not necessary to identify it.

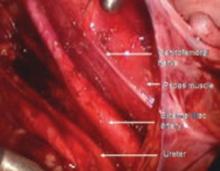

FIGURE 12 Right genitofemoral nerve

The genitofemoral nerve runs along the medial aspect of the body of the psoas muscle. It is sometimes injured by the self-retaining retractors placed at the time of laparotomy. This leads to some numbness and burning of the skin of the anterior thigh.

FIGURE 13 Right pelvic sidewall anatomy

The obturator nerve is in the obturator space and typically far lateral to the usual dissection. Metastatic cancer to the obturator lymph nodes may entrap it, or it may be injured during a node dissection, causing loss of internal rotation of the anterior thigh.

The sciatic nerve is seen only during exenterative surgery. Pressure on the lateral pelvis by advanced pelvic tumors can lead to sciatic pain and motor weakness—even loss of motor function to the lower leg, which commonly leads to foot drop.

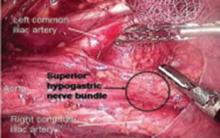

FIGURE 14 Superior hypogastric nerve bundle

The hypogastric plexus of nerves is sometimes damaged during surgery for endometriosis or for malignancy. The superior hypergastric plexus can be identified between the 2 common iliac arteries at the sacral promontory. The left common iliac vein runs underneath it.