Far less often, hyperthyroidism in pregnancy has a cause other than Graves’ disease; TABLE 2 summarizes the possibilities.1 Other causes of hyperthyroidism in early pregnancy include choriocarcinoma and gestational trophoblastic disease (partial and complete moles) (TABLE 3).

TABLE 2

Causes of hyperthyroidism in pregnancy

| Graves’ disease |

| Adenoma |

| Toxic nodular goiter |

| Thyroiditis |

| Excessive thyroid hormone intake |

| Choriocarcinoma |

| Molar pregnancy |

TABLE 3

What causes severe hyperthyroidism before 20 weeks’ gestation?

| Gestational transient thyrotoxicosis |

| Choriocarcinoma |

Gestational trophoblastic disease

|

Signs and symptoms of Graves’ disease

Women who have Graves’ disease usually have thyroid nodules and may have exophthalmia, pretibial myxedema, and tachycardia. They also display other classic signs and symptoms of hyperthyroidism, such as muscle weakness, tremor, and warm and moist skin.

During pregnancy, Graves’ disease usually becomes worse during the first trimester and postpartum period; symptoms resolve during the second and third trimesters.1

Thyrotoxin receptor and antithyroid antibodies

Antithyroid antibodies are common in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease, as a response to thyroid antigens. The two most common antithyroid antibodies are thyroglobulin and thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO). Anti-TPO antibodies are associated with postpartum thyroiditis and fetal and neonatal hyperthyroidism. TSH-receptor antibodies include thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI) and TSH-receptor antibody. TSI is associated with Graves’ disease. TSH-receptor antibody is associated with fetal goiter, congenital hypothyroidism, and chronic thyroiditis without goiter.4

Who do you test for antibodies? Test for maternal thyroid antibodies in patients who:

- had Graves’ disease with fetal or neonatal hyperthyroidism in a previous pregnancy

- have active Graves’ disease being treated with antithyroid drugs

- are euthyroid or have undergone ablative therapy and have fetal tachycardia or intrauterine growth restriction

- have chronic thyroiditis without goiter

- have fetal goiter on ultrasound.

Newborns who have congenital hypothyroidism should also be screened for thyroid antibodies.4

What are the consequences?

Hyperthyroidism can have multiple effects on the pregnant patient and her fetus, ranging in severity from the minimal to the catastrophic.

Gestational transient thyrotoxicosis

This condition is presumably related to high levels of human chorionic gonadotropin, a substance known to stimulate TSH receptors. Unhappily for your patient, the condition is usually heralded by severe bouts of nausea and vomiting starting at 4 to 8 weeks’ gestation. Laboratory tests show significantly elevated levels of FT4 and FT3 and suppressed TSH. Despite this significant derangement, patients generally have no evidence of a hypermetabolic state.

This condition resolves by 14 to 20 weeks of gestation, is not associated with poor pregnancy outcomes, and does not require treatment with antithyroid medication.1

Adverse pregnancy outcomes

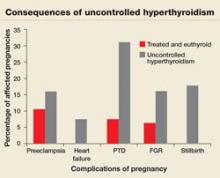

Pregnant women who have uncontrolled hyperthyroidism are at increased risk of spontaneous miscarriage, congestive heart failure, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, and preeclampsia.1 Studies that evaluated pregnancy outcomes in 239 women with overt hyperthyroidism showed increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, compared with treated, euthyroid women (FIGURE 1).5-7

FIGURE 1 Consequences of uncontrolled hyperthyroidism

Several studies have found a much higher risk of pregnancy complications in women who have uncontrolled hyperthyroidism, compared with their treated and euthyroid peers.5-7

PTD=preterm delivery; FGR=fetal growth restrictions.

Fetal and neonatal hyperthyroidism

Hyperthyroidism in the fetus or newborn is caused by placental transfer of maternal immunoglobulin antibodies (TSI) to the fetus and is associated with maternal Graves’ disease. The incidence of neonatal hyperthyroidism is less than 1%. It can be predicted by rising levels of maternal TSI antibodies, to the point where levels in the third trimester are three to five times higher than they were at the beginning of pregnancy.4

Fetal hyperthyroidism develops at about 22 to 24 weeks’ gestation in mothers with a history of Graves’ disease who have been treated surgically or with ablative therapy prior to pregnancy. Even when these therapies achieve a euthyroid state in the mother, TSI levels may remain elevated and lead to fetal hyperthyroidism.

Characteristics of hyperthyroidism in the fetus include tachycardia, intrauterine growth restriction, congestive heart failure, oligohydramnios, and goiter. Treating the mother with antithyroid medications will ameliorate symptoms in the fetus.4

Thyroid storm

This is the worst-case scenario—a rare but potentially lethal complication of uncontrolled hyperthyroidism. Thyroid storm is a hypermetabolic state characterized by fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, tachycardia, altered mental status, restlessness, nervousness, seizures, coma, and cardiac arrhythmias. It occurs in 1% to 2% of patients receiving thioamide therapy.8

In most instances, thyroid storm is a complication of uncontrolled hyperthyroidism, but it can also be precipitated by infection, surgery, thromboembolism, preeclampsia, labor, and delivery.

Thyroid storm is a medical emergency

This manifestation of uncontrolled hyperthyroidism is so urgent that treatment should be initiated before the results of TSH, FT4, and FT3 tests are available.2,8 Delivery should be avoided, if possible, until the mother’s condition can be stabilized but, if the status of the fetus is compromised, delivery is indicated.