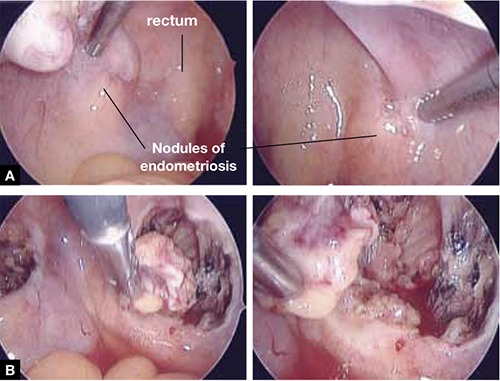

As the bottom panel of FIGURE 5 shows, excised nodules were deep and large; neither laser nor electrosurgery would have been able to ablate or devitalize the deep endometriosis at the base of these 2-cm nodules.

FIGURE 5 Deep nodules present a surgical challenge

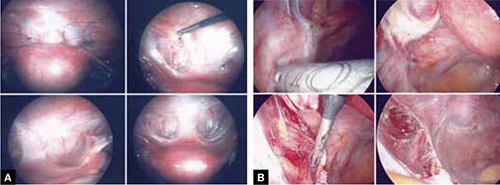

These nodules of endometriosis on the right and left uterosacral ligaments (panel A) did not respond to CO2 laser ablation. Upon progressive resection, the implants were found to be deep, extending into the perirectal space (panel B). (See also VIDEO 3, resection of endometriosis from the left uterosacal ligament, close to the ureter.) FIGURE 6, illustrates endometriosis overlying the bladder and left ureter (see also VIDEO 4). Ablation of endometriosis in these areas may be inadequate if it is not deep enough, and dangerous if it goes too deep. As FIGURE 6 shows, excision assures the surgeon that the entire lesion has been removed and that underlying vital structures have been safeguarded.

FIGURE 6 Urinary tract involvement

Endometriosis overlying the bladder is grasped, retracted, and resected (panel A). Endometriosis compresses the left ureter (panel B). The peritoneum above the lesion is entered, the ureter is displaced laterally, and the lesion is safely resected.

What we do, and recommend

When endometriosis is superficial and does not overlie vital organs, such as the bladder, ureter, and bowel, ablation and resection may be equally safe and effective. When endometriosis is deep and overlying vital organs, however, complete resection—with careful dissection of the lesion off underlying structures—offers a more complete and a safer surgical approach.

CASE continued

Now that S. D. has been treated surgically by complete excision of endometriosis, adhesions, and endometriomas, you must consider a management plan that will reduce the risks 1) of recurrence of symptoms and disease and 2) that further surgery will be necessary in the future—a risk that, in her case, exceeds 50% because of her young age, nulliparity, and the severity of her disease.20,21 Indeed, you are aware that, had preventive measures been implemented after her initial surgery 2 years earlier, it is unlikely that S. D. would have developed the second endometrioma and most likely that she would not have needed the second surgery.

Prevention of recurrence is necessary—and doable

The importance of implementing preventive measures to reduce the risk of recurrence of endometriosis and its symptoms has been suggested by several studies. It was underscored recently in a prospective, randomized study conducted by Serracchioli and colleagues,22 in which 239 women who had undergone laparoscopic resection of endometriomas were randomly assigned to expectant management (control group), a cyclic oral contraceptive (OC), or a continuous oral contraceptives for 24 months, and evaluated every 6 months.

At the end of the study, recurrence of symptoms occurred in 30% of controls; 15% of subjects taking a cyclic OC; and 7.5% of the subjects taking a continuous OC. The recurrence rate of endometrioma in this study was reduced by 50% (cyclic OC) and 75% (continuous OC).22

Similar results were reported in a case-controlled study by Vercellini and co-workers,23 who found that the risk of recurrence of endometrioma was reduced by 60% when postoperative OCs were used long-term and by 30% when used for a duration of less than 12 months.

These studies suggest that, by suppressing ovulation and inducing a state of hypomenorrhea or amenorrhea, the risk of recurrence of endometriosis and its symptoms can be significantly reduced.

The importance of amenorrhea in reducing the postoperative recurrence of endometriosis and symptoms has been underscored by two important studies that evaluated the role of postoperative endometrial ablation or postoperative insertion of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS; Mirena), neither of which suppresses ovulation but both of which induce a state of hypomenorrhea or amenorrhea.24,25

In a prospective randomized study by Bulletti and co-workers,24 28 patients who had symptomatic endometriosis underwent laparoscopic conservative surgery. Endometrial ablation was performed in 14 of the 28. Two years later, all patients underwent second-look laparoscopy; recurrence of endometriosis was found in 9 of the 14 non-ablation patients but in none in the ablation group. Resolution or significant improvement of symptoms were reported in 13 of 14 women in the ablation group but only in 3 of 14 in the non-ablation group—supporting the premise that amenorrhea or hypomenorrhea by itself, without suppressing ovulation, significantly reduces the risk that endometriosis will recur.

Similar beneficial results from hypomenorrhea/amenorrhea on the risk of recurrence of symptoms have been reported when the LNG-IUS is inserted following conservative surgery for endometriosis. In a prospective study by Vercellini and colleagues,25 40 symptomatic patients who had stage-III or stage-IV disease were randomized to either insertion of the LNG-IUS or a control group after conservative laparoscopic surgery. Recurrence of pain was significantly (P = .012) reduced in the LNG-IUS group (45%), compared with the control group (10%). Control subjects were also much less satisfied with their treatment than those who were treated with the LNG-IUS.