Whenever a bowel injury is visualized intraoperatively, assume that it is transmural until it is proved otherwise.

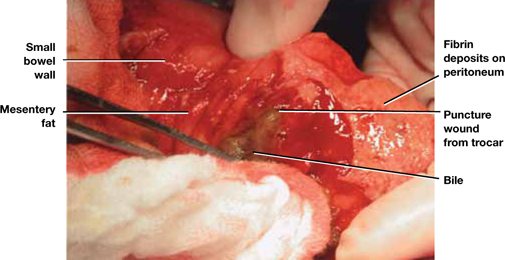

FIGURE 2 Meticulous bowel inspection can identify perforation

It is vital to inspect the bowel after any dissection that involves the intestine, being especially alert for puncture wounds caused by a trocar and small tears associated with adhesiolysis.

SOURCE: Baggish MS, Karram MM. Atlas of Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2011:1142.

How to avoid urinary tract injuries

Along with major vessel injury and intestinal perforation, bladder and ureteral injuries are the most common complications of laparoscopic surgery. Although urinary tract injuries are rarely fatal, they can cause a range of sequelae, including urinoma, vesicovaginal and ureterovaginal fistulas, hydroureter, hydronephrosis, renal damage, and kidney atrophy.

The incidence of ureteral injury during laparoscopy ranges from less than 0.1% to 1.0%, and the incidence of bladder injury ranges from less than 0.8% to 2.0%.23-26 Investigators in Singapore described eight urologic injuries among 485 laparoscopic hysterectomies and identified several risk factors:

- previous cesarean delivery

- multiple fibroids

- severe endometriosis.27

Another set of investigators found a history of laparotomy to be a risk factor for bladder injury during laparoscopic hysterectomy.28

Rooney and colleagues studied the effect of previous cesarean delivery on the risk of injury during hysterectomy.29 Among 5,092 hysterectomies—including 433 laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomies, 3,140 abdominal procedures, and 1,539 vaginal operations—the rate of bladder injury varied by approach. Cystotomy was observed in 0.76% of abdominal hysterectomies (33% had a previous cesarean delivery), 1.3% of vaginal procedures (21% had a previous cesarean), and 1.8% of laparoscopic operations (62.5% had a previous cesarean). The odds ratio for cystotomy during hysterectomy among women with a previous cesarean delivery was 1.26 for the abdominal approach, 3.00 for the vaginal route, and 7.50 for laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy.29

Two studies highlight common aspects of injury

In a recent report of 75 urinary tract injuries associated with laparoscopic surgery, Baggish identified a total of 33 injuries involving the bladder and 42 of ureteral origin. Twelve of the bladder injuries were associated with the approach, and 21 were related to the surgery. In contrast, only one of the 42 ureteral injuries was related to the approach.30

Baggish also found that just under 50% of urinary tract injuries were related to the use of thermal energy, including all three vesicovaginal fistulas. Fourteen bladder lacerations occurred during separation of the bladder from the uterus during laparoscopic hysterectomy.30

Common sites of injury were at the infundibulopelvic ligament, between the infundibulopelvic ligament and the uterine vessels, and at or below the uterine vessels.30

None of the 42 ureteral injuries were diagnosed intraoperatively. In fact, 37 of these injuries were not correctly diagnosed until more than 48 hours after surgery. Two uterovaginal fistulas were also diagnosed in the late postoperative period.30

Bladder injuries were identified via cystoscopy or cystometrogram or by the instillation of methylene blue into the bladder, with observation from above for leakage. Ureteral injuries were identified by IV pyelogram, retrograde pyelogram, or attempted passage of a stent. Every ureteral injury showed up as hydroureter and hydronephrosis via pyelography.30

Grainger and colleagues reported five ureteral injuries associated with laparoscopic procedures.31 The principal symptoms were low back pain, abdominal pain, leukocytosis, and peritonitis. All five injuries were associated with endometriosis surgery, most commonly near the uterosacral ligaments.

Grainger and colleagues cited eight additional cases of injury. Three patients among the 13 total cases lost renal function, and two eventually required nephrectomy.31

How to prevent, identify, and manage urinary tract injuries

Thorough knowledge of anatomy and meticulous technique are imperative to prevent urinary tract injuries. Strategies include:

- Use sharp rather than blunt dissection.

- Know the risk factors for urinary tract injury, which include previous cesarean delivery or intra-abdominal surgery, presence of adhesions, and deep endometriosis.

- Be aware of the dangers posed by energy devices when they are used near the bladder and ureter. Even bipolar devices can cause thermal injury.

- Employ hydrodissection when there are bladder adhesions, and work nearer the uterus or vagina than the bladder, leaving a margin of tissue.

- When the ureter’s location is unclear relative to the operative site, do not hesitate to open the retroperitoneal space to observe the ureter. If necessary, dissect the ureter distally.

- Perform cystoscopy with IV indigo carmine injection at the conclusion of surgery to ensure that the ureter is not occluded.

- Be aware that peristalsis is not an indication of ureteral integrity. In fact, an obstructed ureter will pulsate more vigorously than a normal one.

- Consider preoperative ureteral catheterization, which may avert injury without increasing operative time, blood loss, and hospital stay,32 although the data are not definitive.33

- Be vigilant. Early identification of injuries reduces morbidity. In the case of ureteral obstruction, immediate stenting will usually obviate the need for ureteral implantation and nephrostomy if the obstruction is not complete.

- Intervene early to cut an obstructing suture or relieve ureteral bowing. Doing so may eliminate the obstruction altogether in many cases.

- If a laceration is found in the bladder trigone or its vicinity, always perform ureteral catheterization to help prevent the inadvertent suturing of the intravesical ureter into the repair.

- After repair of a bladder laceration, perform cystoscopy with IV injection of indigo carmine to ensure ureteral integrity.

- Use only absorbable suture in bladder repairs. I recommend 2-0 chromic catgut for the first layer, which should encompass muscularis and mucosa. Place a second layer of sutures using 3-0 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl), imbricating the first layer.

- After completion of a bladder repair, instill a solution of diluted methylene blue (1 part methylene blue to 100 parts sterile water or saline) to distend the bladder, and carefully inspect the closure to ensure that it is watertight. Then place a Foley catheter for a minimum of 2 weeks. Four to 6 weeks after repair, perform a cystogram to ensure that healing is complete, with no leakage.

- Call a urologist if you are not well-versed in bladder repair, or if the ureter is injured (or injury is suspected).

- Watch for fistula formation, an inevitable outcome of untreated bladder and ureteral injury, which may occur early or late in the postoperative course.