Clinical Review

UPDATE: CONTRACEPTION

Unpredictable bleeding with progestin-only contraceptives can lead to dissatisfaction and discontinuation. The authors scrutinize the reported...

The pendulum swung in the next decade to broader networks in which consumers had much greater access, but premiums increased by an average of 11% per year.6 Employers then pushed insurers to reduce premium costs, leading back to narrow networks in the years just before the ACA. Narrow network plans accounted for 23% of all employer-sponsored plans in 2012, up from 15% in 2007.6

Increasing consolidation contributes to narrow networks

The trend toward narrower networks is also linked to increasing consolidation in health care. As health systems grow and individual or small group practices disappear, insurers rely on being able to credibly threaten to exclude systems and big groups from their networks as leverage in payment negotiations. By restricting the choice of providers in a plan, the insurer can promise more customers for the doctors and hospitals that are included, and negotiate lower payments to those providers.

The downside for physicians is clear:

The insurance industry’s position is that patients have choices. Plans with access to more hospitals and specialists are available but usually at a higher price.

Narrow networks are one way to achieve low premiums

In the months leading up to ACA enactment, insurers got to work developing plans designed to be sold on the exchanges that would attract consumers through low-cost premiums and still maximize profits, especially now that insurers, under the ACA, are barred from excluding sick enrollees or increasing premiums for women, in addition to other important protections.

In previous articles, we’ve explored these landmark protections. Insurers in the individual market used to be able to keep premiums relatively low, and profits up, through use of preexisting coverage exclusions, benefit exclusions including noncoverage for maternity care or prescription drugs, and high cost sharing. Not anymore.

Since enactment of the ACA, narrow networks seem to be the preferred, and most effective, payment negotiation tool of many insurers offering plans through the exchanges, reflecting the trend we’re already seeing in the private health insurance marketplace.

NPR spotlights the difficulty of finding a specialist

The consumer and provider problems of narrow networks have been gaining attention in the media. In July, the National Public Radio (NPR) Web site carried an article entitled, “Patients with low-cost insurance struggle to find specialists,” with a key subtitle: “So you found an exchange plan. But can you find a provider?”7

In the NPR article, author Carrie Feibel reported on the situation in a majority-immigrant area of southwest Houston.

There, many patients at the local clinic have health insurance coverage for the first time, an important step toward healthier lives for themselves and their families. But many people in need of a specialist are learning that their insurance card doesn’t guarantee them access to a needed surgeon or hospital. They’ve purchased a narrow-network insurance plan, with a low premium but few specialists who accept that insurance.7

The two largest hospital chains in Houston—Houston Methodist and Memorial Hermann—as well as Houston’s MD Anderson Cancer Center, don’t participate in the Blue Cross Blue Shield HMO Silver plan, a plan popular with low-income consumers because of its low premium.7

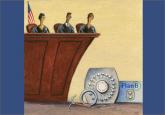

Will the government take action?

The ACA actually guards against overly narrow networks and established the first national standard for network adequacy—a standard that needs fuller development, for sure. Plans sold on the exchanges are required to establish networks that include, among other providers, essential community providers, who typically care for mostly low-income and medically underserved populations. Networks also must include sufficient numbers and types of providers, including “providers that specialize in mental health and substance abuse services, to assure that all services will be accessible without unreasonable delay.”8

Insurers also must provide people who are considering purchasing their products with an accurate directory—both online and a hard copy—identifying providers not accepting new patients in the network. And plans are prohibited from charging out-of-network cost-sharing for emergency services.

Much of the oversight and many of the details—how much is adequate? what is unreasonable?—are left to the states, many of which have years of experience grappling with the downsides and delicate balance of networks.

The Urban Institute points out that Vermont and Delaware set standards for maximum geographic distance and drive times for primary care services. In California, plans must make it easy for consumers to reach urban providers on public transportation.6

Unpredictable bleeding with progestin-only contraceptives can lead to dissatisfaction and discontinuation. The authors scrutinize the reported...

Know the facts behind the accusations and counter-claims so you can point your patients toward cost-effective coverage

Drugs such as tamoxifen and raloxifene are now covered without co-pays or co-insurance

Federal and state legislators have made numerous attempts to interfere in the patient-doctor relationship in recent years, and ACOG has stepped up...

Contraception now is covered for most insured patients, but two cases before the Supreme Court could unravel this new guarantee