First-episode psychosis (FEP) in schizophrenia is characterized by high response rates to antipsychotic therapy, followed by frequent antipsychotic discontinuation and elevated relapse rates soon after maintenance treatment begins.1,2 With subsequent episodes, time to response progressively increases and likelihood of response decreases.3,4

To address these issues, this article—the second of 2 parts5—describes the rationale and evidence for using nonstandard first-line antipsychotic therapies to manage FEP. Specifically, we discuss when clinicians might consider monotherapy exceeding FDA-approved maximum dosages, combination therapy, long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIA), or clozapine.

Monotherapy beyond FDA-approved dosages

Treatment guidelines for FEP recommend oral antipsychotic dosages in the lower half of the treatment range and lower than those that are required for multi-episode schizophrenia.6-16 Ultimately, clinicians prescribe individualized dosages for their patients based on symptom improvement and tolerability. The optimal dosage at which to achieve a favorable D2 receptor occupancy likely will vary from patient to patient.17

To control symptoms, higher dosages may be needed than those used in FEP clinical trials, recommended by guidelines for FEP or multi-episode patients, or approved by the FDA. Patients seen in everyday practice may be more complicated (eg, have a comorbid condition or history of nonresponse) than study populations. Higher dosages also may be reasonable to overcome drug−drug interactions (eg, cigarette smoking-mediated cytochrome P450 1A2 induction, resulting in increased olanzapine metabolism),18 or to establish antipsychotic failure if adequate trials at lower dosages have resulted in a suboptimal response and the patient is not experiencing tolerability or safety concerns.

In a study of low-, full-, and high-dosage antipsychotic therapy in FEP, an additional 15% of patients responded to higher dosages of olanzapine and risperidone after failing to respond to a standard dosage.19 A study of data from the Recovery After an Initial Schizophrenia Episode Project’s Early Treatment Program (RAISE-ETP) found that, of participants identified who may benefit from therapy modification, 8.8% were prescribed an antipsychotic (often, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol) at a higher-than-recommended dosage.20 Of note, only olanzapine was prescribed at higher than FDA-approved dosages.

Antipsychotic combination therapy

Prescribing combinations of antipsychotics—antipsychotic polypharmacy (APP)— has a negative connotation because of limited efficacy and safety data,21 and limited endorsement in schizophrenia treatment guidelines.9,13 Caution with APP is warranted; a complex medication regimen may increase the potential for adverse effects, poorer adherence, and adverse drug-drug interactions.9 APP has been shown to independently predict both shorter treatment duration and discontinuation before 1 year.22

Nonetheless, the clinician and patient may share the decision to implement APP and observe whether benefits outweigh risks in situations such as:

• to optimize neuroreceptor occupancy and targets (eg, attempting to achieve adequate D2 receptor blockade while minimizing side effects secondary to binding other receptors)

• to manage co-existing symptom domains (eg, mood changes, aggression, negative symptoms, disorganization, and cognitive deficits)

• to mitigate antipsychotic-induced side effects (eg, initiating aripiprazole to treat hyperprolactinemia induced by another antipsychotic to which the patient has achieved a favorable response).23

Clinicians report using APP to treat as many as 50% of patients with a history of multiple psychotic episodes.23 For FEP patients, 23% of participants in the RAISE-ETP trial who were identified as possibly benefiting from therapy modification were prescribed APP.20 Regrettably, researchers have not found evidence to support a reported rationale for using APP—that lower dosages of individual antipsychotics when used in combination may avoid high-dosage prescriptions.24

Before implementing APP, thoroughly explore and manage reasons for a patient’s suboptimal response to monotherapy.25 An adequate trial with any antipsychotic should be at the highest tolerated dosage for 12 to 16 weeks. Be mindful that response to an APP trial may be the result of additional time on the original antipsychotic.

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics in FEP

Guideline recommendations. Most older guidelines for schizophrenia treatment suggest LAIA after multiple relapses related to medication nonadherence or when a patient prefers injected medication (Table 1).6-13 Expert consensus guidelines also recommend considering LAIA in patients who lack insight into their illness. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) guidelines7 state LAIA can be considered for inadequate adherence at any stage, whereas the 2010 British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP) guidelines9 express uncertainty about their use in FEP, because of limited evidence. Both the BAP and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines13 urge clinicians to consider LAIA when avoiding nonadherence is a treatment priority.

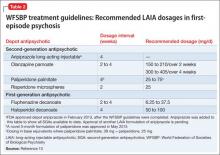

Recently, the French Association for Biological Psychiatry and Neuro-psychopharmacology (AFPBN) created expert consensus guidelines12 on using LAIA in practice. They recommend long-acting injectable second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) as first-line maintenance treatment for schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder and for individuals experiencing a first recurrent episode. The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry guidelines contain LAIA dosage recommendations for FEP (Table 2).10

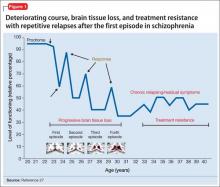

Advances have been made in understanding the serious neurobiological adverse effects of psychotic relapses, including neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, that may explain the atrophic changes observed with psychotic episodes starting with the FEP. Protecting the patient from a second episode has become a vital therapeutic management goal26 (Figure 127).

Concerns. Compared with oral antipsychotics, LAIA offers clinical advantages:

• improved pharmacokinetic profile (lower “peaks” and higher “valleys”)

• more consistent plasma concentrations (no variability related to administration timing or food effects)

• no first-pass metabolism, which can ease the process of finding the lowest effective and safe dosage

• reduced administration burden and objective tracking of adherence with typical dosing every 2 to 4 weeks

• less stigmatizing than oral medication for FEP patients, such as college students living in a dormitory.28,29