Mr. N, age 48, has chronic mental illness and has been in and out of psychiatric hospitals for 30 years, with diagnoses of bipolar disorder, not otherwise specified, without psychotic features and schizophrenia. He often is delusional and disorganized and does not adhere to treatment. Since age 18, his psychiatric care has been sporadic; during his last admission 3 years ago, he refused treatment and left the hospital against medical advice. Mr. N is homeless and often eats out of a dumpster.

Recently, Mr. N was arrested for cocaine possession, for which he was held in custody. His mental status continued to deteriorate while in jail, where he was evaluated by a forensics examiner.

Mr. N was declared incompetent to stand trial and was transferred to a state psychiatric hospital.

In the hospital, the treatment team finds that Mr. N is disorganized and preoccupied with thoughts of not wanting to “lose control” to the physicians. He shows no evidence of suicidal or homicidal ideation or perceptual disturbance. Mr. N has difficulty grasping concepts, making plans, and following through with them. He has poor insight and impulse control and impaired judgment.

Mr. N’s past and present diagnoses include bipolar disorder without psychotic features, schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, paranoid personality traits, borderline intelligence, cellulitis of both legs, and chronic venous stasis. Although he was arrested for cocaine possession, we are not able to obtain much information about his history of substance abuse because of his poor mental status.

What could be causing Mr. N’s deteriorating mental status?

a) substance withdrawal

b) malnutrition

c) worsening schizophrenia

d) untreated infection due to cellulitis

HISTORY Sporadic care

Mr. N can provide few details of his early life. He was adopted as a child. He spent time in juvenile detention center. He completed 10th grade but did not graduate from high school. Symptoms of mental illness emerged at age 18. His employment history is consistent with chronic mental illness: His longest job, at a grocery store, lasted only 6 months. He has had multiple admissions to psychiatric hospitals. Over the years his treatment has included divalproex sodium, risperidone, paroxetine, chlorpromazine, thioridazine, amitriptyline, methylphenidate, and a multivitamin; however, he often is noncompliant with treatment and was not taking any medications when he arrived at the hospital.

EVALUATION Possible deficiency

The treatment team discusses guardianship, but the public administrator’s office provides little support because of Mr. N’s refusal to stay in one place. He was evicted from his last apartment because of hoarding behavior, which created a fire hazard. He has been homeless most of his adult life, which might have significantly restricted his diet.

A routine laboratory workup—complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, liver function test, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and lipids—is ordered, revealing an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) in the low range at 1,200/μL (normal range, 1,500 to 8,000/μL). Mr. N is offered treatment with a long-acting IM injection of risperidone because of his history of noncompliance, but he refuses the medication. Instead, he is started on oral risperidone, 2 mg/d.

The cellulitis of both lower limbs and chronic venous stasis are of concern; the medical team is consulted. Review of Mr. N’s medical records from an affiliated hospital reveals a history of vitamin B12 deficiency. Further tests show that the vitamin B12 level is low at <50 pg/mL (normal range, 160 to 950 pg/mL). Pernicious anemia had been ruled out after Mr. N tested negative for antibodies to intrinsic factor (a glycoprotein secreted in the stomach that is necessary for absorption of vitamin B12). Suspicion is that vitamin B12 deficiency is caused by Mr. N’s restricted diet in the context of chronic homelessness.

The authors’ observations

A review of the literature on vitamin B12 deficiency describes tingling or numbness, ataxia, and dementia; however, in rare cases, vitamin B12 deficiency presents with psychiatric symptoms, such as depression, mania, psychosis, dementia, and catatonia.1-13

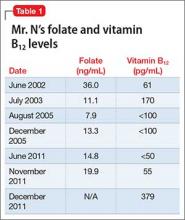

We suspected that Mr. N’s vitamin B12 deficiency could have been affecting his mental status; consequently, we ordered routine laboratory work-up that included a complete blood count with differential and peripheral smear, which showed macrocytic anemia and ovalocytes. We also tested his vitamin B12 level, which was very low at 55 pg/mL. These results, combined with his previously recorded vitamin B12 level (Table 1), suggested deficiency.

TREATMENT Oral medication

Two months after starting risperidone, the medical team recommends IM vitamin B12 as first-line treatment, but Mr. N refuses. We considered guardianship ex parte for involuntary administration of IM B12 injection to prevent life-threatening consequences of a non-healing ulcer on his leg that was related to his cellulitis. Meanwhile, we reviewed the literature on vitamin B12 therapy, including route, dosage, and outcome.14-23 Mr. N agrees to oral vitamin B12, 1,000 μg/d,21 and we no longer consider guardianship ex parte. Mr. N’s vitamin B12 level and clinical picture improve 1 month after oral vitamin B12 is added to oral risperidone. His thought process is more organized, he is no longer paranoid, and he shows improved insight and judgement. ANC and neutrophil count improve as well (Table 2). Mr. N’s ulcer begins to heal despite his noncompliance with wound care.