Your patient who has schizophrenia, Mr. W, age 48, requests that you switch him from olanzapine, 10 mg/d, to another antipsychotic because he gained 25 lb over 1 month taking the drug. He now weighs 275 lb. Mr. W reports smoking at least 2 packs of cigarettes a day and takes lisinopril, 20 mg/d, for hypertension. You decide to start risperidone, 1 mg/d. First, however, your initial work-up includes:

- high-density lipoprotein (HDL), 24 mg/dL

- total cholesterol, 220 mg/dL

- blood pressure, 154/80 mm Hgwaist circumference, 39 in

- body mass index (BMI), 29

- hemoglobin A1c, of 5.6%.

A prolactin level is pending.

How do you interpret these values?

Metabolic syndrome is defined as the cluster of central obesity, insulin resistance, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. Metabolic syndrome increases a patient's risk of diabetes 5-fold and cardiovascular disease 3-fold.1 Physical inactivity and eating high-fat foods typically precede weight gain and obesity that, in turn, develop into insulin resistance, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.1

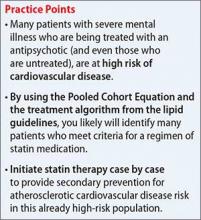

Patients with severe psychiatric illness have an increased rate of mortality from cardiovascular disease, compared with the general population.2-4 The cause of this phenomenon is multifactorial: In general, patients with severe mental illness receive insufficient preventive health care, do not eat a balanced diet, and are more likely to smoke cigarettes than other people.2-4

Also, compared with the general population, the diet of men with schizophrenia contains less vegetables and grains and women with schizophrenia consume less grains. An estimated 70% of patients with schizophrenia smoke.4 As measured by BMI, 86% of women with schizophrenia and 70% of men with schizophrenia are overweight or obese.4

Antipsychotics used to treat severe mental illness also have been implicated in metabolic syndrome, specifically second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs).5 Several theories aim to explain how antipsychotics lead to metabolic alterations.

Oxidative stress. One theory centers on the production of oxidative stress and the consequent reactive oxygen species that form after SGA treatment.6

Mitochondrial function. Another theory assesses the impact of antipsychotic treatment on mitochondrial function. Mitochondrial dysfunction causes decreased fatty acid oxidation, leading to lipid accumulation.7

The culminating affect of severe mental illness alone as well as treatment-emergent side effects of antipsychotics raises the question of how to best treat the dyslipidemia component of metabolic syndrome. This article will:

- review which antipsychotics impact lipids the most

- provide an overview of the most recent lipid guidelines

- describe how to best manage patients to prevent and treat dyslipidemia.

Impact of antipsychotics on lipids

Antipsychotic treatment can lead to metabolic syndrome; SGAs are implicated in most cases.8 A study by Liao et al9 investigated the risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia in patients with schizophrenia who received treatment with a first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) compared with patients who received a SGA. The significance-adjusted hazard ratio for the development of hyperlipidemia in patients treated with a SGA was statistically significant compared with the general population (1.41; 95% CI, 1.09-1.83). The risk of hyperlipidemia in patients treated with a FGA was not significant.

Studies have aimed to describe which SGAs carry the greatest risk of hyperlipidemia.10,11 To summarize findings, in 2004 the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and American Psychiatric Association released a consensus statement on the impact of antipsychotic medications on obesity and diabetes.12 The statement listed the following antipsychotics in order of greatest to least impact on hyperlipidemia:

- clozapine

- olanzapine

- quetiapine

- risperidone

- ziprasidone

- aripiprazole.

To evaluate newer SGAs, a systematic review and meta-analysis by De Hert et al13 aimed to assess the metabolic risks associated with asenapine, iloperidone, lurasidone, and paliperidone. In general, the studies included in the meta-analysis showed little or no clinically meaningful differences among these newer agents in terms of total cholesterol in short-term trials, except for asenapine and iloperidone.

Asenapine was found to increase the total cholesterol level in long-term trials (>12 weeks) by an average of 6.53 mg/dL. These trials also demonstrated a decrease in HDL cholesterol (−0.13 mg/dL) and a decrease in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) (−1.72 mg/dL to −0.86 mg/dL). The impact of asenapine on these lab results does not appear to be clinically significant.13,14

Iloperidone. A study evaluating the impact iloperidone on lipid values showed a statistically significant increase in total cholesterol, HDL, and LDL-C levels after 12 weeks.13,15

Overview: Latest lipid guidelines

Current literature lacks information regarding statin use for overall prevention of metabolic syndrome. However, the most recent update to the American Heart Association's guideline on treating blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults describes the role of statin therapy to address dyslipidemia, which is one component of metabolic syndrome.16,17

Some of the greatest changes seen with the latest blood cholesterol guidelines include: