Imagine being able to precisely select the medication with the optimal efficacy, safety, and tolerability at the outset of treatment for every psychiatric patient who needs pharmacotherapy. Imagine how much the patient would appreciate not receiving a series of drugs and suffering multiple adverse effects and unremitting symptoms until the “right medication” is identified. Imagine how gratifying it would be for you as a psychiatrist to watch every one of your patients improve rapidly with minimal complaints or adverse effects.

Precision psychiatry is the indispensable vehicle to achieve personalized medicine for psychiatric patients. Precision psychiatry is a cherished goal, but it remains an aspirational objective. Other medical specialties, especially oncology and cardiology, have made remarkable strides in precision medicine, but the journey to precision psychiatry is still in its early stages. Yet there is every reason to believe that we are making progress toward that cherished goal.

To implement precision psychiatry, we must be able to identify the biosignature of each patient’s psychiatric brain disorder. But there is a formidable challenge to overcome: the complex, extensive heterogeneity of psychiatric disorders, which requires intense and inspired neurobiology research. So, while clinicians go on with the mundane trial-and-error approach of contemporary psychopharmacology, psychiatric neuroscientists are diligently deconstructing major psychiatric disorders into specific biotypes with unique biosignatures that will one day guide accurate and prompt clinical management.

Psychiatric practitioners may be too busy to keep tabs on the progress being made in identifying various biomarkers that are the key ingredients to decoding the biosignature of each psychiatric patient. Take schizophrenia, for example. There are myriad clinical variations that comprise this heterogeneous brain syndrome, including level of premorbid functioning; acute vs gradual onset of psychosis; the type and severity of hallucinations or delusions; the dimensional spectrum of negative symptoms and cognitive impairments; the presence and intensity of suicidal or homicidal urges; and the type of medical and psychiatric comorbidities. No wonder every patient is a unique and fascinating clinical puzzle, and yet, patients with schizophrenia are still being homogenized under a single DSM diagnostic category.

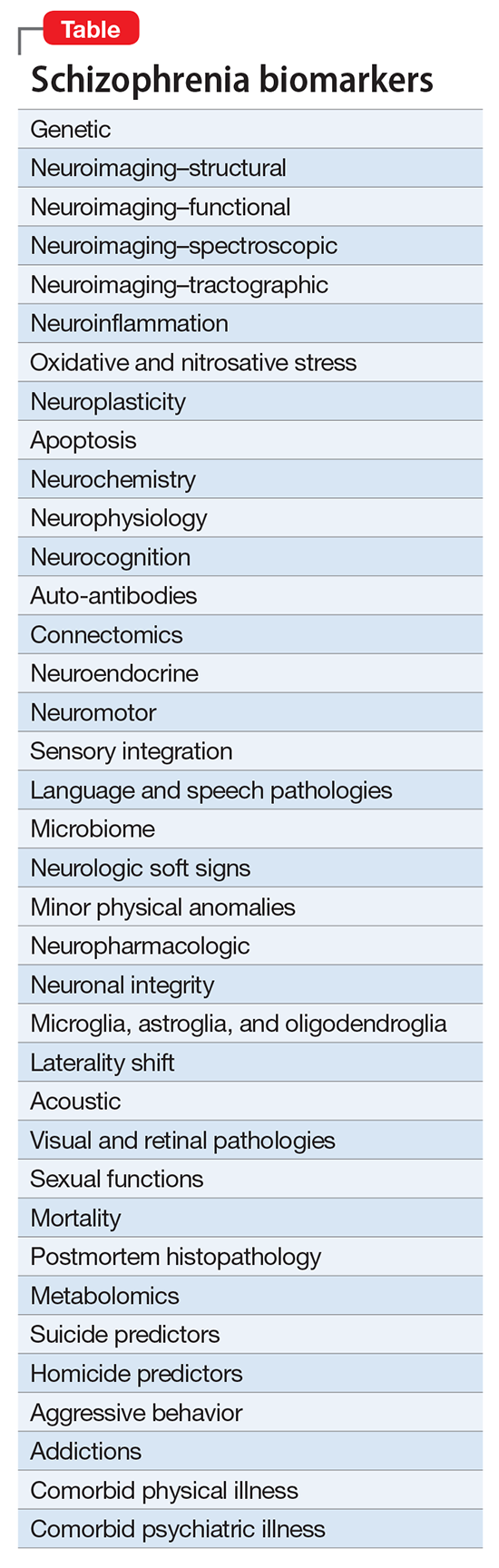

In the meantime, psychiatric investigators are stratifying schizophrenia into its many endophenotypes, and linking hundreds of schizophrenia biotypes to an array of biomarkers (Table) that can be diagnostic, predictive, prognostic, or useful in monitoring efficacy or safety.There are hundreds of biomarkers in schizophrenia,1 but none can be used clinically until the biosignatures of the many diseases within the schizophrenia syndrome are identified. That grueling research quest will take time, given that so far >340 risk genes for schizophrenia have been discovered, along with countless copy number variants representing gene deletions or duplications, plus dozens of de novo mutations that preclude coding for any protein. Add to these the numerous prenatal pregnancy adverse events, delivery complications, and early childhood abuse—all of which are associated with neurodevelopmental disruptions that set up the brain for schizophrenia spectrum disorders in adulthood—and we have a perplexing conundrum to tackle.