Weight gain is a potential problem for all patients who require treatment with antipsychotics. Those with schizophrenia face double jeopardy. Both the disorder and the use of virtually any available antipsychotic drug may be associated with weight gain, new-onset glucose intolerance, and type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Because of the cardiovascular risks and other morbidity associated with weight gain and glucose dysregulation,1 the psychiatrist must remain vigilant and manage these complications aggressively. In this article, we offer insights into the prevention and management of metabolic complications associated with the use of antipsychotic agents in patients with schizophrenia.

Weight gain and antipsychotics

Weight change was recognized as a feature of schizophrenia even before antipsychotic drugs were introduced in the 1950s.2 Schizophrenia—independent of drug treatment—also is a risk factor for the development of type 2 diabetes. In persons with schizophrenia, serum glucose levels increase more slowly, decline more gradually, and represent higher-than-normal reference values.3

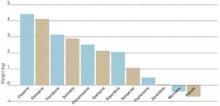

Figure 1 WEIGHT GAIN ASSOCIATED WITH ANTIPSYCHOTIC DRUG ADMINISTRATION

Values represent estimates of drug-induced weight gain after 10 weeks of drug administration.

Source: Allison et al. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1686-96; Brecher et al. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract 2000;4:287-92.In 1999, Allison et al assessed the effects of conventional and atypical antipsychotics on body weight. Using 81 published articles, they estimated and compared weight changes associated with 10 antipsychotic agents and a placebo when given at standard dosages for 10 weeks.4 Comparative data on quetiapine, which were insufficient in 1999, have since been added (Figure 1).5

Patients who received a placebo lost 0.74 kg across 10 weeks. Weight changes with the conventional agents ranged from a reduction of 0.39 kg with molindone to an increase of 3.19 kg with thioridazine. Weight gains also were seen with all of the newer atypical agents, including clozapine (+4.45 kg), olanzapine (+4.15 kg), risperidone (+2.10 kg), and ziprasidone (+0.04 kg).

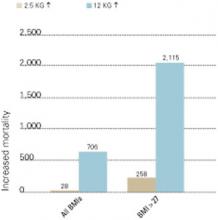

Fontaine et al have estimated that weight gain in patients with schizophrenia has its greatest impact on mortality in two scenarios:

- when patients are overweight before they start antipsychotic medication

- with greater degrees of weight gain across 10 years (Figure 2).

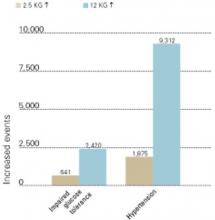

Whatever a patient’s starting weight, substantial weight gain with antipsychotic therapy increases the risk of impaired glucose tolerance and hypertension (Figure 3).6

Schizophrenia and diabetes

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes in patients with schizophrenia increased from 4.2% in 1956 to 17.2% in 1968, related in part to the introduction of phenothiazines.7 A recent study of data collected by the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT)2 found higher rates of diabetes in persons with schizophrenia (lifetime prevalence, 14.9%) than in the general population (approximately 7.3%).1 Most patients in the PORT study were taking older antipsychotics, the use of which has occasionally been associated with carbohydrate dysregulation.

Figure 2 INCREASED MORTALITY ASSOCIATED WITH WEIGHT GAIN

Number of deaths associated with weight gains of 2.5 and 12 kg over 10 years, as related to all body mass index measurements (BMIs) and BMIs >27 (per 100,000 persons in U.S. population).

Source: Fontaine et al. Psychiatry Res 2001;101:277-88.The prevalence of new-onset diabetes with use of specific antipsychotics is unknown. Most information is contained in case reports, and proper epidemiologic studies await publication.

The most detailed report—a pooled study of published cases related to clozapine use—comes from the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.8 In this study, the authors identified 384 reports of diabetes that developed (in 242 patients) or was exacerbated (in 54 patients) in association with clozapine. Patient mean age was 40, and diabetes occurred more commonly in women than in men.

Diabetes developed most commonly within 6 months of starting treatment with clozapine, and one patient developed diabetes after a single 500-mg dose. Metabolic acidosis or ketosis occurred in 80 cases, and 25 subjects died during hyperglycemic episodes. Stopping clozapine or reducing the dosage improved glycemic control in 46 patients.8

Figure 3 INCREASED MORBIDITY ASSOCIATED WITH WEIGHT GAIN

New cases of impaired glucose tolerance and hypertension that developed with weight gains of 2.5 and 12 kg over 10 years (per 100,000 persons in U.S. population).

Source: Fontaine et al. Psychiatry Res 2001;101:277-88.During antipsychotic therapy, it is important to measure patients’ fasting plasma glucose at least annually—and more often for high-risk patients (Table 1). The American Diabetes Association defines diabetes as a fasting serum or plasma glucose 126 mg/dl or a 2-hour postprandial serum or plasma glucose 200 mg/dl. In all patients, these tests should be repeated to confirm the diagnosis. Oral glucose tolerance testing is less convenient than fasting plasma glucose testing but more sensitive in identifying changes in carbohydrate metabolism.