History: Initial symptoms

Ms. G, 17, has battled attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) since age 6, and within the past 2 years was also diagnosed as having schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. An outpatient child psychiatrist and a therapist have helped keep her symptoms in control through much of her life.

During one recent visit to her psychiatrist, however, she complained of decreased energy, increased crying spells, broken sleep, and a depressed mood. She reported that these symptoms began approximately 2 months before the visit, and neither she nor her parents could identify a clear-cut cause.

Throughout her life she has complied with her drug regimens. For 2 years she has been taking divalproex sodium, 500 mg twice daily to manage her manic and depressive episodes, dextroamphetamine sulfate, 30 mg in the morning for her ADHD; risperidone, 2 mg at bedtime for her psychotic symptoms; and mestranol, 60 mcg/d, plus norethindrone, 1 mg/d, for contraception. A recent valproic acid reading of 62 μg/ml is consistent with levels over the last 2 years.

During previous psychotic episodes, Ms. G often became delusional and paranoid with command-type hallucinations. She destroyed her room during her most recent episode.

Ms. G’s adoptive mother accompanied her during this visit. She is concerned for her daughter, especially with the start of school about 1 month away.

Which would you address first: the depression or the psychosis? Would you change Ms. G’s medication and if so, how?

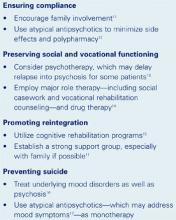

Figure 1 DEPRESSION IN SCHIZOPHRENIA: IMPROVING OUTCOMES

Drs. Yu’s and Maguire’s observations

Complaints of depression in a patient with schizoaffective disorder are especially concerning because multiple domains could be affected (Figure 1). For patients with schizophrenia, the 60% lifetime incidence of major depressive disorder substantially exceeds the 8 to 26% risk in the general population. Ms. G’s comorbid depression also may predispose her to an increased rate of relapse into schizoaffective psychosis, poor treatment response, and a longer duration of psychotic illness that could require hospitalization.1

Although Ms. G’s divalproex level was therapeutic (between 50 and 100 μg/ml), some data indicate that valproic acid may be less effective in schizoaffective disorder than in bipolar I disorder. Still, treatment of schizoaffective disorder often follows antimanic and antidepressant protocols.2

Treatment: An agent is added

The outpatient psychiatrist adds fluoxetine, 20 mg each morning, to address Ms. G’s depressive symptoms. She reports no improvement after 1 month, and her fluoxetine is increased to 30 mg/d.

Three weeks later, Ms. G’s parents bring her to the psychiatrist for an emergency visit. She reports suicidal ideation over the previous month. Rolling up both sleeves, she reveals several superficial cuts on her forearms and wrists that she inflicted after breaking up with her boyfriend.

Her mother, appearing anxious and overwhelmed, reports that her daughter pushed her because she had refused to give Ms. G her calling card. She had told her mother that she wanted to call a boy in Utah that she had met over the Internet.

Ms. G’s speech is noticeably pressured and she is extremely distractible. Her mother notes that her daughter is sleeping only 2 to 3 hours a night, yet exhibits no decrease in energy. Still depressed, her affect is markedly labile, crying at one moment when discussing her suicidality, then railing at her mother when she tries to explain Ms. G’s aggressiveness. When the psychiatrist recommends hospitalization to stabilize her symptoms, she vehemently demands to be let out so that she can run in front of a moving car. The police are called, and she is restrained and brought into the hospital.

What caused Ms. G’s sudden decline? How would you address it?

Drs. Yu’s and Maguire’s observations

Although antidepressants can effectively treat depression in schizoaffective disorder, many of these medications can trigger a manic episode,3 which can include mania, mixed mania with depression, or rapid cycling every few days or hours. In Ms. G’s case, an increase in serotonin due to the fluoxetine may have caused her mania.

We would stop the fluoxetine and see if her manic symptoms resolve. Fluoxetine’s long half-life (4 to 16 days) cuts down the odds of a serotonin-discontinuation syndrome, making immediate discontinuation feasible.

Still, the cause of Ms. G’s depressive symptoms remains unknown. At this stage, observation in the adolescent inpatient ward holds our best hope of reaching a definitive diagnosis.

Treatment: A diagnostic clue surfaces

Blood tests on admission (including a negative drug screen for narcotics or other depressogenic substances) are normal, and her valproic acid level is 61 μg/ml. Her divalproex is increased to 500 mg in the morning and 750 mg at bedtime, and she is tapered off fluoxetine. Her symptoms gradually improve with the change in the medications and her attendance in milieu and group therapy on the ward. A second valproic acid reading on day three of hospitalization is 67 μg/ml.