Among a sample of 1,410 chronic schizophrenia patients enrolled in the NIMH-sponsored CATIE, 19% were involved in either minor or serious violent behavior in the past 6 months and 3.6% in serious violent behavior.4

Nobody argues that someone with schizophrenia is clearly at higher risk of becoming violent when in a high arousal state with positive symptoms or unpleasant delusions or hallucinations. A person with schizophrenia who is in an agitated, aroused psychotic state with active paranoid delusions and hallucinations is clearly at higher risk for committing violence.5,6 The patient who has been charged in the beating death of Dr. Fenton was a 19-year-old man with severe psychosis.

Dr. Krahn: Are there other disorders, such as bipolar mania, that are high risk for patient violence?

Dr. Battaglia: Acute manic states are higher risk.7 But, again, the diagnosis of bipolar disorder in and of itself does not show an increased incidence of violence. Personality disorders can be higher risk, as can nonspecific neurologic abnormalities, such as abnormal EEGs or neurologic “soft signs” by exam or testing.

Dr. Krahn: What about substance abuse?

Dr. Battaglia: The risk of violence is higher in patients who are under the influence of certain stimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamines, as opposed to marijuana or sedatives.8

Dr. Krahn: How can we predict whether a patient is at high risk for assault?

Dr. Battaglia: The best predictor is a history of violence, especially when the act was unprovoked or resulted in injury.9 A small number of patients is responsible for the majority of aggression. One study showed that recidivists committed 53% of all violent acts in a health care setting.10

Dr. Krahn: What if the patient’s history is unknown?

Dr. Battaglia: Most assaults in health care occur in high arousal states. Planned, methodical assaults are significantly less frequent. So, in the case of patients making threats against staff—let’s say you terminated your relationship with a patient and obtained a restraining order—very commonly that patient’s passion toward the clinic will wane over time.

Dr. Krahn: But not every arousal state results in assault.

Dr. Battaglia: Right. I have a colleague who says, “Risk factors make you worry more, and nothing makes you worry less.” That’s the attitude to have. Nothing should make you lower your antenna.

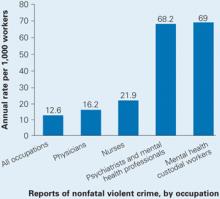

Source: U.S. Department of Justice, National Crime Victimization Survey, 1993 to 1999

Dr. Krahn: Is the risk higher with a new patient, or does it go down as you establish a relationship?

Dr. Battaglia: Clearly, untreated patients in high arousal states are a much greater risk. Does risk go down with somebody you’ve known for a while? I don’t know. My own experiences with assault have sometimes occurred with people I’ve grown to trust and when I let my guard down.

Dr. Krahn: So we might relax once we know the patient, but then we might be more vulnerable. Any clues that should put us on high alert?

Dr. Battaglia: The first clue—and this is going to sound obvious—is our internal, visceral, emotional sense of impending danger. In my experience, psychiatrists have a very good sense of that, but we override or don’t pay attention to it. Part of that inattention is an occupational hazard; we have to turn off our sense of danger again and again so that we can stay in situations that would repulse most people.

For instance, medical students with no psychiatric experience might sit in an interview with an agitated patient and feel an intense need to flee. Their antennae are telling them the situation looks dangerous. Seasoned psychiatrists, however, will calm themselves and stay through the interview. We are so used to being healers and helpers that we often turn off or dampen our sense of danger.

Dr. Krahn: Can you elaborate?

Dr. Battaglia: A nurse and I were with a patient who was highly agitated. He was labile; he was angry; he was spitting as he was speaking. In any other context, people would be keeping their distance because the signals were so powerful. Instead, the nurse leaned in, held his hand, and started telling him, “Come on now (Bob), you need to settle down. This is scaring us.”

That’s what I call the “leaning-in response.” We do that day in and day out. We turn off our danger signals in order to be therapeutic, and that makes us vulnerable.

Dr. Krahn: So, how do we keep our signals tuned?

Dr. Battaglia: When our senses are telling us we’re scared or we’re noticing a feeling of wanting to flee, we have to shift away from the goal of being therapeutic and focus on the goal of harm reduction. In assault cases, two clinician errors I see are: