Potentially fatal neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS)—though less common than in the past—can happen with either conventional or atypical antipsychotics.1,2 To help you protect patients when prescribing antipsychotics or consulting with other clinicians about these drugs, this article discusses:

- risk factors and clinical features that warn of NMS onset

- differential diagnosis of disease states most often confused with NMS

- management recommendations, including supportive measures and specific interventions such as benzodiazepines, dopamine agonists, dantrolene, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

WHY NMS REMAINS RELEVANT

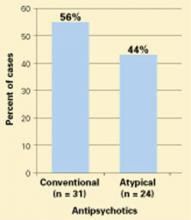

NMS remains a risk in susceptible patients receiving atypical antipsychotics, according to clinical reports and drug adverse event surveys (Figure).2

Moreover, NMS continues to be reported with conventional antipsychotics, which remain in widespread use. Patients who receive long-acting depot conventional antipsychotics are at risk for prolonged NMS episodes.

Figure 55 NMS cases reported with use of antipsychotics, 1998-2002

Probable or definite neuroleptic malignant syndrome cases associated with antipsychotic monotherapy reported to the Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome Information Service.NMS in medical settings. Psychiatrists may be consulted when patients develop NMS while receiving conventional antipsychotics or other dopaminereceptor antagonists used in medical settings.3,4 Haloperidol remains the recommended drug of choice for treating agitation and delirium and continues to be the single most common trigger of NMS. Although often overlooked, antiemetics and sedatives with neuroleptic properties—such as prochlorperazine, metoclopramide, and promethazine—also have triggered NMS.

Other hyperthermic conditions. NMS is often considered in the differential diagnosis of patients who develop fever or encephalopathy while being treated with psychotropics. In these acute, complex, and often grave situations, psychiatrists may be consulted to recommend treatment for behavioral control or to distinguish NMS from other conditions.

NEWER VS. OLDER ANTIPSYCHOTICS

Has NMS incidence declined with the atypical agents? Probably, but providing proof is difficult:

- NMS is uncommon; its incidence in psychiatric patients treated with conventional antipsychotics is approximately 0.2%.5 To demonstrate reduced NMS incidence with atypicals, a very large sample of patients would be required to reach statistical significance.

- As doctors have used lower doses of conventional agents—which reduces the risk of NMS—any beneficial impact from atypicals has become more difficult to detect.5,6

- Reports of NMS frequency with atypicals may be inflated by bias in publishing adverse events with newer versus older agents.

- Patients switched to atypicals may represent a high-risk group that is intolerant or resistant to conventional antipsychotics.

So far, few unequivocal cases of NMS have been attributed to the use of quetiapine, ziprasidone, or aripiprazole, the most recently introduced atypicals. Moreover, case reports of NMS associated with clozapine, risperidone, or olanzapine2 are often difficult to interpret because of incomplete clinical details, varying diagnostic criteria, and concomitant use of more than one antipsychotic.

Milder NMS? Do the newer antipsychotics produce an “atypical” or milder form of NMS? Case reports indicate that extreme temperature elevations and extrapyramidal dysfunction are less frequent in NMS associated with atypical compared with conventional antipsychotics.2 However, case descriptions of NMS were heterogeneous even with conventional agents, and clinicians’ growing awareness of NMS even before atypicals were introduced allowed for earlier diagnosis of mild and partial NMS cases.7

CLINICAL FEATURES OF NMS

Regardless of drug selection, it is important to recognize early and mild signs of NMS. Any case can progress to a fulminant form that is more difficult to treat.

Patients at risk. NMS may be more likely to develop in patients with:5,6,8

- dehydration

- agitation

- low serum iron

- underlying brain damage

- catatonia.

Some patients may have genetic abnormalities in central dopamine systems that increase their susceptibility to NMS.6,9

Fifteen to 20% of patients who develop NMS have experienced a previous episode while taking antipsychotics, which is why taking a careful drug history is important.5,6 Although most often reported with therapeutic antipsychotic doses, NMS has been associated with rapid dose titration, especially when given parenterally.8

On the other hand, the practical value of these risk factors is often limited in individual cases and may lead one to overestimate NMS risk. NMS is rare and idiosyncratic. Risk factors may not outweigh antipsychotics’ benefits when these drugs are indicated for a patient with psychosis.

Incipient NMS. Identifying early signs of NMS may be impossible in fulminant cases, but patients with incipient NMS may show:

- unexpected mental status changes

- new-onset catatonia

- refractory extrapyramidal and bulbar signs such as rigidity, dysphagia, or dysarthria.5,7,10

Other clues to NMS onset include tachycardia, tachypnea, and elevated temperature or serum creatine phosphokinase (CPK). These signs, however, do not precede or progress to NMS in all cases. A high index of suspicion for NMS, tempered by sound clinical judgment, is called for when assessing all patients receiving antipsychotics.