Dear Dr. Mossman:

My patient, Ms. X, returned to see me after she had spent 3 months in jail. When I accessed her medication history in our state’s prescription registry, I discovered that, during her incarceration, a local pharmacy continued to fill her prescription for clonazepam. After anxiously explaining that her roommate had filled the prescriptions, Ms. X pleaded with me not to tell anyone. Do I have to report this to legal authorities? If I do, will I be breaching confidentiality?

Submitted by Dr. L

Preserving the confidentiality of patient encounters is an ethical responsibility as old as the Hippocratic Oath,1 but protecting privacy is not an absolute duty. As psychiatrists familiar with the Tarasoff case2 know, clinical events sometimes create moral and legal obligations that outweigh our confidentiality obligations.

What Dr. L should do may hinge on specific details of Ms. X’s previous and current treatment, but in this article, we’ll examine some general issues that affect Dr. L’s choices. These include:

• reporting a past crime

• liability risks associated with violating confidentiality.

Monitoring controlled substances

Dr. L’s clinical situation probably would not have arisen 10 years ago because until recently, she would have had no easy way to learn that Ms. X’s prescription had been filled. In 2002, Congress responded to increasing concern about “epidemic” abuse of controlled substances—especially opioids—by authorizing state grants for prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs).3

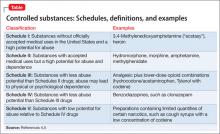

PDMPs are internet-based registries that let physicians quickly find out when and where their patients have filled prescriptions for controlled substances (defined in the Table).4,5 As the rate of opioid-related deaths has risen,6 at least 43 states have initiated PDMPs; soon, all U.S. jurisdictions likely will have such programs.7 Data about the impact of PDMPs, although limited, suggest that PDMPs reduce “doctor shopping” and prescription drug abuse.8

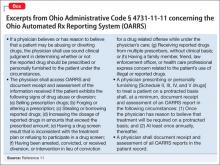

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is promoting the development of electronic architecture standards to facilitate information exchange across jurisdictions,9 but states currently run their own PDMPs independently and have varying regulations about how physicians should use PDMPs.10 Excerpts from the rules used in Ohio’s prescription reporting system appear in the Box.11

Reporting past crimes

What Ms. X told Dr. L implies that someone—the patient, her roommate, or both—misused a prescription to obtain a controlled substance. Simple improper possession of a scheduled drug is a federal misdemeanor offense,12 and deception and conspiracy to obtain a scheduled drug are federal-level felonies.13 Such actions also violate state laws. Dr. L therefore knows that a crime has occurred.

Are doctors obligated or legally required to breach confidentiality and tell authorities about a patient’s past criminal acts? Writing several years ago, Appelbaum and Meisel14 and Goldman and Gutheil15 said the answer, in general, is “no.”

In recent years, state legislatures have modified criminal codes to encourage people to disclose their knowledge of certain crimes to police. For example, failures to report environmental offenses and financial misdealings have become criminal acts.16 A minority of states now punish failure to report other kinds of illegal behavior, but these laws focus mainly on violent crimes (often involving harm to vulnerable persons).17 Although Ohio has a law that obligates everyone to report knowledge of any felony, it makes exceptions when the information is learned during a customarily confidential relationship—including a physician’s treatment of a patient.18 Unless Dr. L herself has aided or concealed a crime (both illegal acts19), concerns about possible prosecution should not affect her decision to report what she has learned thus far.14

Deciding how to proceed

If Dr. L still feels inclined to do something about the misused prescription, what are her options? What clinical, legal, and moral obligations to act should she consider?

Obtain the facts. First, Dr. L should try to learn more about what happened. Jails are reluctant to give inmates benzodiazepines20; did Ms. X receive clonazepam while in jail? When and how did Ms. X learn about her roommate’s actions? Did Ms. X obtain previous prescriptions from Dr. L with the intention of letting her roommate use them? Answers to these questions can help Dr. L determine whether her patient participated in prescription misuse, an important factor in deciding what clinical or legal actions to take.