“He has always been a negative person,” she adds, and confirms that he has been depressed for most of their marriage.

The conflict between Mr. M’s earlier expressed preference for full care and his current wish to withdraw life-sustaining therapies and experience a “natural death” raises significant concern that depression could explain this change in perspective. When asked about this discrepancy, Mr. M admits that he “wanted everything done” in the past, when he was younger and healthier, but his preferences changed as his chronic medical problems progressed.

OUTCOME Better mood, discharge

We encourage Mr. M to continue discussing his treatment preferences with his family, while meeting with the palliative care team to address medical conditions that could be exacerbating depression and to clarify his goals of care. The medical team and Mr. M report feeling relieved when a palliative care consult is suggested, although his wife and son ask that it be delayed until Mr. M is more medically stable. The treatment team acknowledges the competing risks of proceeding too hastily with Mr. M’s request to withdraw life-sustaining treatments because of depression, and of delaying his decision, which could prolong suffering and violate his right to refuse medical treatment.

Mr. M agrees to increase citalopram to 40 mg/d to target depressive symptoms. We monitor Mr. M for treatment response and side effects, to provide ongoing support, to facilitate communication with the medical team, and to evaluate the influence of depression on treatment preferences and decision-making.

As Mr. M is stabilized over the next 3 weeks, he begins to reply, “I’m alive,” when asked about passive death wish. His renal function improves and RRT is discontinued. Mr. M reports a slight improvement in his mood and is discharged to a skilled nursing facility, with plans for closing his tracheostomy.

The authors’ observations

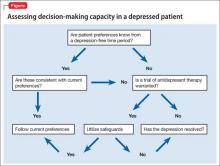

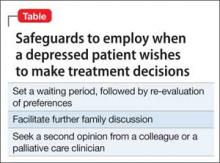

Capacity assessments can be challenging in depressed patients, often because of the uncertain role of features such as hopelessness, anhedonia, and passive death wish in the decision-making process. Depressed patients do not automatically lack DMC, and existing studies suggest that decisions regarding life-saving interventions typically are stable across time. The 4-ability model for capacity assessment is a useful starting point, but additional considerations are warranted in depressed patients with chronic illness (Figure). There is no evidence to date to guide these assessments in chronically depressed or dysthymic patients; therefore additional safeguards may be needed (Table).

In Mr. M’s case, the team’s decision to optimize depression treatment while continuing unwanted life-sustaining therapies led to improved mood and a positive health outcome. In some cases, patients do not respond quickly, if at all, to depression treatment. Also, what constitutes a reasonable attempt to treat depression, or an appropriate delay in decision-making related to life-sustaining therapies, is debatable.

When positive outcomes are not achieved or ethical dilemmas arise, health care providers could experience high moral distress.21 In Mr. M’s case, the consultation team felt moral distress because of the delayed involvement of palliative care, especially because this decision was driven by the family rather than the patient.

Related Resources

• Sessums LL, Zembrzuska H, Jackson JL. Does this patient have medical decision-making capacity? JAMA. 2011;306(4):420-427.

• American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. www. aahpm.org.

Drug Brand Names

Buspirone • Buspar Citalopram • Celexa

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.