As the Food and Drug Administration focuses on other issues, companies, both big and small, are looking to boost physician and consumer interest in their “medical foods” – products that fall somewhere between drugs and supplements and promise to mitigate symptoms, or even address underlying pathologies, of a range of diseases.

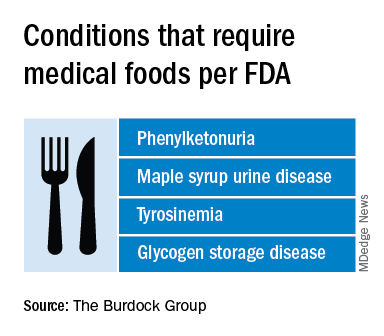

Manufacturers now market an array of medical foods, ranging from powders and capsules for Alzheimer disease to low-protein spaghetti for chronic kidney disease (CKD). The FDA has not been completely absent; it takes a narrow view of what medical conditions qualify for treatment with food products and has warned some manufacturers that their misbranded products are acting more like unapproved drugs.

By the FDA’s definition, medical food is limited to products that provide crucial therapy for patients with inborn errors of metabolism (IEM). An example is specialized baby formula for infants with phenylketonuria. Unlike supplements, medical foods are supposed to be used under the supervision of a physician. This has prompted some sales reps to turn up in the clinic, and most manufacturers have online approval forms for doctors to sign. Manufacturers, advisers, and regulators were interviewed for a closer look at this burgeoning industry.

The market

The global market for medical foods – about $18 billion in 2019 – is expected to grow steadily in the near future. It is drawing more interest, especially in Europe, where medical foods are more accepted by physicians and consumers, Meghan Donnelly, MS, RDN, said in an interview. She is a registered dietitian who conducts physician outreach in the United States for Flavis, a division of Dr. Schär. That company, based in northern Italy, started out targeting IEMs but now also sells gluten-free foods for celiac disease and low-protein foods for CKD.

It is still a niche market in the United States – and isn’t likely to ever approach the size of the supplement market, according to Marcus Charuvastra, the managing director of Targeted Medical Pharma, which markets Theramine capsules for pain management, among many other products. But it could still be a big win for a manufacturer if they get a small slice of a big market, such as for Alzheimer disease.

Defining medical food

According to an update of the Orphan Drug Act in 1988, a medical food is “a food which is formulated to be consumed or administered enterally under the supervision of a physician and which is intended for the specific dietary management of a disease or condition for which distinctive nutritional requirements, based on recognized scientific principles, are established by medical evaluation.” The FDA issued regulations to accompany that law in 1993 but has since only issued a guidance document that is not legally binding.

Medical foods are not drugs and they are not supplements (the latter are intended only for healthy people). The FDA doesn’t require formal approval of a medical food, but, by law, the ingredients must be generally recognized as safe, and manufacturers must follow good manufacturing practices. However, the agency has taken a narrow view of what conditions require medical foods.

Policing medical foods hasn’t been a priority for the FDA, which is why there has been a proliferation of products that don’t meet the FDA’s view of the statutory definition of medical foods, according to Miriam Guggenheim, a food and drug law attorney in Washington, D.C. The FDA usually takes enforcement action when it sees a risk to the public’s health.

The agency’s stance has led to confusion – among manufacturers, physicians, consumers, and even regulators – making the market a kind of Wild West, according to Paul Hyman, a Washington, D.C.–based attorney who has represented medical food companies.

George A. Burdock, PhD, an Orlando-based regulatory consultant who has worked with medical food makers, believes the FDA will be forced to expand their narrow definition. He foresees a reconsideration of many medical food products in light of an October 2019 White House executive order prohibiting federal agencies from issuing guidance in lieu of rules.