Risk Factors

Quadriceps and thigh injuries comprise approximately 4.5% of injuries among NFL players.7 Several risk factors for quadriceps strains have been described. In a study of Australian Rules football players, Orchard35 demonstrated that for all muscle strains, the strongest risk factor was a recent history of the same injury, with the next strongest risk factor being a past history of the same injury. Increasing age was found to be a risk factor for hamstring strains but not quadriceps strains. Muscle fatigue may also contribute to injury susceptibility.36

History and Physical Examination

Injuries typically occur during kicking, jumping, or a sudden change in direction while running.30 Athletes may localize pain anywhere along the quadriceps muscle, although strains most commonly occur at the proximal to mid portion of the rectus femoris.30,33 The grading system for quadriceps strains described by Kary30 is based on level of pain, quadriceps strength, and the presence or absence of a palpable defect (Table 2).

In high-grade strains, a sharp pain occurs immediately following the injury and often causes variable degrees of functional loss to the quadriceps.30The athlete typically walks with an antalgic gait. Visible swelling and/or ecchymosis may be present depending on when the athlete is seen, as ecchymosis may develop within the first 24 hours of injury. The examiner should palpate along the entire length of the injured muscle. High-grade strains or complete tears may present with a bulge or defect in the muscle belly, but in most cases no defect will be palpable. There may be loss of knee flexion similar to a quadriceps contusion. Strength testing should be performed in both the sitting and prone position with the hip both flexed and extended to assess resisted knee extension strength.30 Loss of strength is proportional to the degree of injury.

Imaging

While most quadriceps strains are adequately diagnosed clinically without the need for imaging studies, ultrasound or MRI can be used to evaluate for partial or complete rupture.30,33 In milder cases, MRI usually demonstrates interstitial edema and hemorrhage with a feathery appearance on STIR and T2-weighted imaging (Figures 3A-3C).11

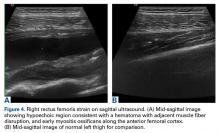

Myotendinous strains can be classified based on the extent of fiber disruption.11,32 Cross and colleagues33 demonstrated that strains of the central tendon of the rectus femoris seen on MRI correlated with a significantly longer rehabilitation period than those occurring at the periphery of the rectus or within other quadriceps muscles. Ultrasound is a more economical imaging modality that can dynamically assess the quadriceps musculature for fiber disruption and hematoma formation but is user-dependent, requiring a skilled technician (Figures 4A, 4B).30Treatment

Acute treatment of quadriceps strains focuses on minimizing bleeding using the principles of RICE treatment.37 NSAIDs may be used immediately to assist with pain control.30 COX-2-specific NSAIDs are preferred due to their lack of any inhibitory effect on platelet function in order to reduce the risk of further bleeding within the muscle compartment. For the first 24 to 72 hours following injury, the quadriceps should be maintained relatively immobilized to prevent further injury.38 High-grade injuries might necessitate crutches for ambulatory assistance.

Depending on injury severity, the active phase of treatment usually begins within 5 days of injury and consists of stretching and knee/hip range of motion. An active warm-up should precede rehabilitation exercises to activate neural pathways within the muscle and improve muscle elasticity.38 Ballistic stretching should be avoided to prevent additional injury to the muscle fibers. Strengthening should proceed when the athlete recovers a pain-free range of motion. When isometric exercises can be completed at increasing degrees of knee flexion, isotonic exercises may be implemented into the rehabilitation program.30 Return to football can be considered when the athlete has recovered knee and hip range of motion, is pain-free, and has near-normal strength compared to the contralateral side. The athlete should also perform satisfactorily in simulated position-specific activities in a noncontact fashion prior to return to full competition.30

Hamstring Strain

Pathophysiology

Hamstring strains are the most common noncontact injuries in football resulting from excessive muscle stretching during eccentric contraction generally occurring at the musculotendinous junction.5,39 Because the hamstrings cross both the hip and knee, simultaneous hip flexion and knee extension results in maximal lengthening, making them most vulnerable to injury at the terminal swing phase of gait just prior to heel strike.39-42 The long head of the biceps femoris undergoes the greatest stretch, reaching 110% of resting length during terminal swing phase and is the most commonly injured hamstring muscle.43,44 Injury occurs when the force of eccentric contraction, and resulting muscle strain, exceeds the mechanical limits of the tissue.42,45 It remains to be shown whether hamstring strains occur as a result of accumulated microscopic muscle damage or secondary to a single event that exceeds the mechanical limits of the muscle.42