Morel-Lavallée Lesion

Pathophysiology

Morel-Lavallée lesions (MLLs) are uncommon football injuries, but often occur in the thigh.57,58 An MLL is a posttraumatic soft tissue injury in which deforming forces of pressure and shear cause a closed, soft tissue degloving injury; in this injury, the skin and subcutaneous tissues are separated from the underlying fascia, disrupting perforating blood vessels. The resulting space between the fascia and subcutaneous tissue fills with blood, lymphatics, and necrotic fat, resulting in a hematoma/seroma that can be a nidus for bacterial infection.58 The most common anatomic regions are the anterior distal thigh and lateral hip. Both of these areas are commonly involved in both direct contact and shear forces following a fall to the ground.

History and Physical Examination

Athletes with MLLs typically present with the insidious onset of a fluid collection within the thigh following a fall to the ground, usually while sliding or diving on the playing surface.57,58 The fluid collection can be associated with thigh tightness and may extend distally into the suprapatellar region or proximally over the greater trochanter. Thigh swelling, ecchymosis, and palpable fluctuance are seen in most cases. Progressive increases in pain and thigh swelling may be seen in severe injuries, but thigh compartments generally remain soft and nontender. Signs and symptoms of an MLL do not typically manifest immediately following the athletic event. Tejwani and colleagues58 reported a case series of MLLs of the knee in 27 NFL players from a single team over a 14-year period, with an average of 3 days between injury and evaluation by the medical staff. The mechanism of injury was a shearing blow from the knee striking the playing surface in 81% of cases and direct contact to the knee from another player in 19% of cases; all cases occurred in game situations. No affected players were wearing kneepads at the time of injury.

Imaging

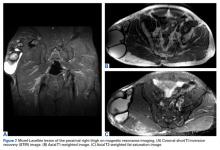

Plain radiography may reveal a noncalcified soft tissue mass over the involved area and is not usually helpful except to rule out an underlying fracture. The appearance of an MLL on ultrasound is nonspecific and variable, often described as anechoic, hypoechoic, or hyperechoic depending on the presence of hemolymphatic fluid sedimentation and varying amounts of internal fat debris. MRI is the imaging modality of choice and typically shows a well-defined oval or fusiform, fluid-filled mass with tapering margins blending with adjacent fascial planes.

These lesions may show fluid-fluid levels, septations, and variable internal signal intensity depending on the acuity of the lesion (Figures 7A-7C).59Treatment

Similar to quadriceps contusions, treatment goals for MLLs are evacuation of the fluid collection, prevention of fluid recurrence, a full range of active knee flexion, and prompt return to play.57,58 Initial treatment for smaller lesions consists of cryotherapy, compression wrapping of the involved area, and immediate active and passive range of motion of the hip and knee. While MLLs were traditionally treated with serial open debridements, less invasive approaches—including elastic compression, aspiration, percutaneous irrigation with debridement and suction drainage, or liposuction and drainage followed by suction therapy—have been recently described.57,58,60,61 Less invasive approaches aim to minimize soft tissue dissection and disruption of the vascular supply while accelerating rehabilitation. The presence of a surrounding capsule on MRI makes conservative or minimally invasive approaches less likely to be successful and may necessitate an open procedure.62 Antibiotics should be used preoperatively due to the presence of a dead space containing necrotic debris that makes infection a potential complication. While elite contact athletes can expect to return to competition long before complete resolution of an MLL, there is a risk of further delamination and lesion expansion due to re-injury prior to compete healing.

Tejwani and colleagues58 performed aspiration at the area of palpable fluctuance in the thigh or suprapatellar region using a 14-gauge needle in those athletes who failed to improve with conservative treatments alone. Mean time to resolution of the fluid collection was 16 days following aspiration. Fifty-two percent of the athletes were successfully treated with cryotherapy, compression, and motion exercises alone; 48% were treated with at least one aspiration, with a mean of 2.7 aspirations per knee. In 11% of cases that failed to resolve after multiple aspirations, doxycycline sclerodesis was performed immediately following an aspiration. Patients treated with sclerodesis had no return of the fluid collection and returned to play the following day.

Matava and colleagues57 described the case of an NFL player who sustained a closed MLL of the lateral hip while diving onto an artificial turf surface attempting to catch a pass. Despite immediate thigh pain and swelling, he was able to continue play. Immediately following the game, the player was examined and had a tense thigh with ecchymosis extending into the trochanteric region. Aspiration of the fluctuant area was unsuccessful. Progressive increases in pain and thigh swelling prompted hospital admission. Percutaneous irrigation and debridement was performed as described by Tseng and Tornetta.61 A suction drain was placed within the residual dead space, and constant wall suction was applied in addition to hip compression using a spica wrap. The player returned to practice 22 days after the injury and missed a total of 3 games without any residual deficit.