Vesiculobullous eruptions in neonates can readily generate anxiety from parents/guardians and pediatricians over both infectious and noninfectious causes. The role of the dermatology resident is critical to help diminish fear over common vesicular presentations or to escalate care in rarer situations if a more obscure or ominous diagnosis is clouding the patient’s clinical presentation and well-being. This article summarizes both common and uncommon vesiculobullous neonatal diseases to augment precise and efficient diagnoses in this vulnerable patient population.

Steps for Evaluating a Vesiculopustular Eruption

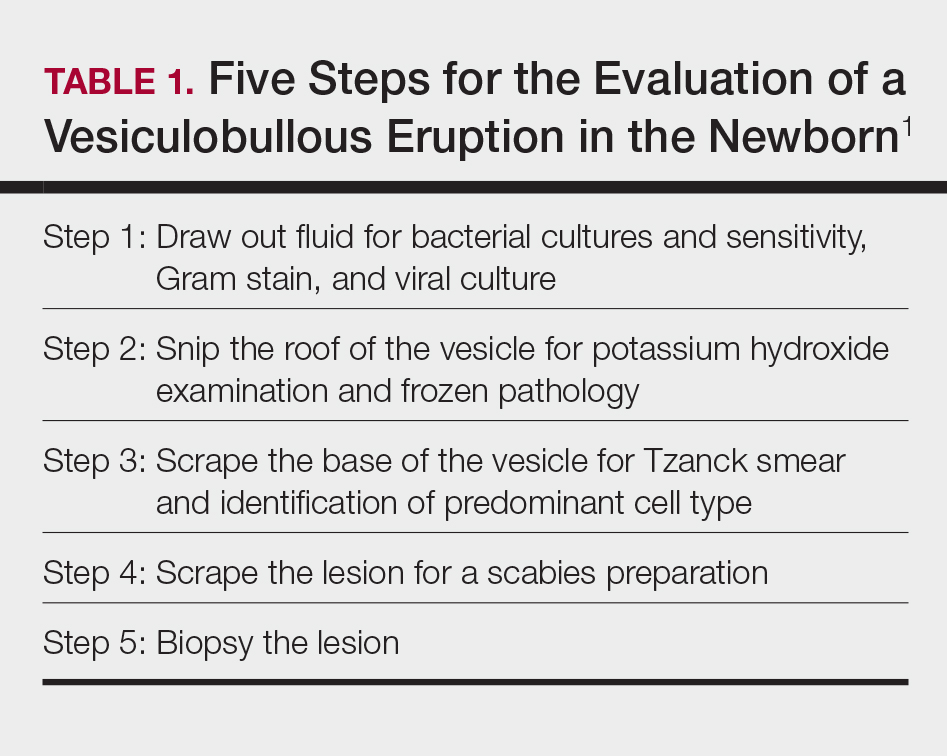

Receiving a consultation for a newborn with widespread vesicles can be a daunting scenario for a dermatology resident. Fear of missing an ominous diagnosis or aggressively treating a newborn for an erroneous infection when the diagnosis is actually a benign presentation can lead to an anxiety-provoking situation. Additionally, performing a procedure on a newborn can cause personal uneasiness. Dr. Lawrence A. Schachner, an eminent pediatric dermatologist at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine (Miami, Florida), recently lectured on 5 key steps (Table 1) for the evaluation of a vesiculobullous eruption in the newborn to maximize the accuracy of diagnosis and patient care.1

First, draw out the fluid from the vesicle to send for bacterial and viral culture as well as Gram stain. Second, snip the roof of the vesicle to perform potassium hydroxide examination for yeast or fungi and frozen pathology when indicated. Third, use the base of the vesicle to obtain cells for a Tzanck smear to identify the predominant cell infiltrate, such as multinucleated giant cells in herpes simplex virus or eosinophils in erythema toxicum neonatorum (ETN). Fourth, a mineral oil preparation can be performed on several lesions, especially if a burrow is observed, to rule out bullous scabies in the appropriate clinical presentation. Lastly, a perilesional or lesional punch biopsy can be performed if the above steps have not yet clinched the diagnosis.2 By utilizing these steps, the resident efficiently utilizes 1 lesion to narrow down a formidable differential list of bullous disorders in the newborn.

Specific Diagnoses

A number of common diagnoses can present during the newborn period and can usually be readily diagnosed by clinical manifestations alone; a summary of these eruptions is provided in Table 2. Erythema toxicum neonatorum is the most common pustular eruption in neonates and presents in up to 50% of full-term infants at days 1 to 2 of life. Inflammatory pustules surrounded by characteristic blotchy erythema are displayed on the face, trunk, arms, and legs, usually sparing the palms and soles.3 Erythema toxicum neonatorum typically is a clinical diagnosis; however, it can be confirmed by demonstrating the predominance of eosinophils on Tzanck smear.

Transient neonatal pustular melanosis (TNPM) also presents in full-term infants; usually favors darkly pigmented neonates; and exhibits either pustules with a collarette of scale that lack surrounding erythema or with residual brown macules on the face, genitals, and acral surfaces. Postinflammatory pigmentary alteration on lesion clearance is another clue to diagnosis. Similarly, it is a clinical diagnosis but can be confirmed with a Tzanck smear demonstrating neutrophils as the major cell infiltrate.

In a prospective 1-year multicenter study performed by Reginatto et al,4 2831 neonates born in southern Brazil underwent a skin examination by a dermatologist within 72 hours of birth to characterize the prevalence and demographics of ETN and TNPM. They found a 21.3% (602 cases) prevalence of ETN compared to a 3.4% (97 cases) prevalence of TNPM, but they noted that most patients were white, and thus the diagnosis of TNPM likely is less prevalent in this group, as it favors darkly pigmented individuals. Additional predisposing factors associated with ETN were male gender, an Apgar score of 8 to 10 at 1 minute, non–neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) patients, and lack of gestational risk factors. The TNPM population was much smaller, though the authors were able to conclude that the disease also was correlated with healthy, non-NICU patients. The authors hypothesized that there may be a role of immune system maturity in the pathogenesis of ETN and thus dermatology residents should be aware of the setting of their consultation.4 A NICU consultation for ETN should raise suspicion, as ETN and TNPM favor healthy infants who likely are not residing in the NICU; we are reminded of the target populations for these disease processes.

Additional common causes of vesicular eruptions in neonates can likewise be diagnosed chiefly with clinical inspection. Miliaria presents with tiny superficial crystalline vesicles on the neck and back of newborns due to elevated temperature and resultant obstruction of the eccrine sweat ducts. Reassurance can be provided, as spontaneous resolution occurs with cooling and limitation of occlusive clothing and swaddling.2