Photo Challenge

Dr. Shaigany is from the Department of Dermatology, New York University Hospital, New York. Drs. Simpson and Micheletti are from the Department of Dermatology, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Micheletti also is from the Department of Medicine.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Correspondence: Robert G. Micheletti, MD, Department of Dermatology, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, 3600 Spruce St, 2 Maloney Bldg, Philadelphia, PA 19104 (Robert.Micheletti@uphs.upenn.edu).

A man in his 60s presented with a subcutaneous nodule on the right side of the chest. Due to impaired mental status, he was unable to describe the precise age of the lesion, but his wife reported it had been present at least several weeks. She recently noted a new, bright red growth on top of the nodule. The lesion was asymptomatic but seemed to be growing in size. Physical examination revealed a 3-cm firm fixed nodule on the right side of the chest with an overlying, exophytic bright red papule. No similar lesions were found elsewhere on physical examination. A punch biopsy of the lesion was performed.

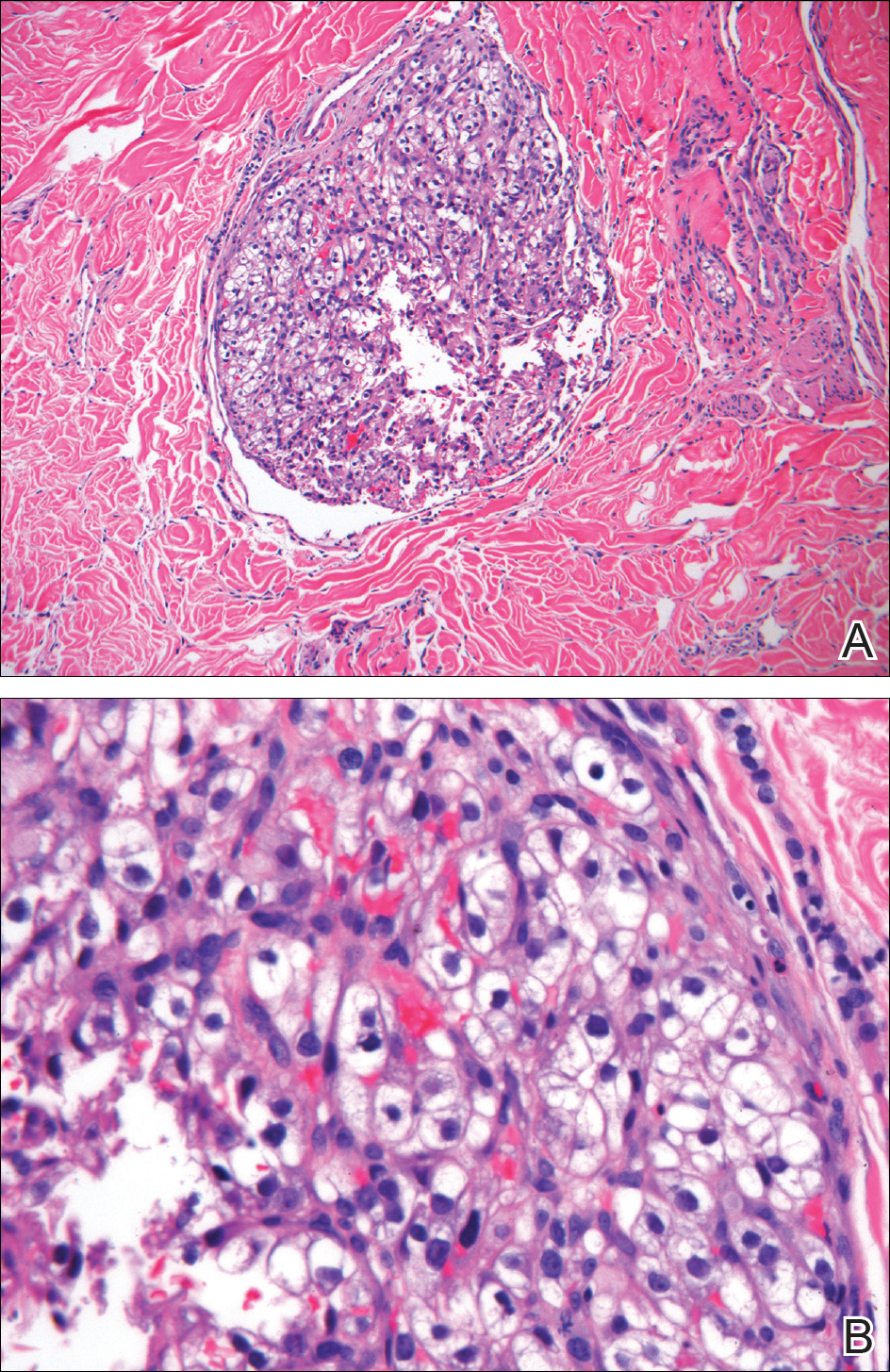

Histopathologic examination of the punch biopsy demonstrated epithelioid cells with abundant clear cytoplasm and numerous chicken wire-like vascular channels consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of renal cell carcinoma (RCC)(Figure). Collateral history revealed that 8 years prior, the patient had been diagnosed with clear cell RCC, stage III (T3aN0M0). At that time, he was treated with radical nephrectomy, which was considered curative. He remained disease free until several months prior to the development of the cutaneous lesion when he was found to have pulmonary and cerebral metastases with biopsies showing metastatic RCC. He was treated with lobectomy and Gamma Knife radiation for the lung and cerebral metastases, respectively. His oncologist planned to initiate therapy with the multikinase inhibitor sunitinib, which inhibits vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling. Unfortunately, the patient died prior to treatment due to overwhelming tumor burden.

Punch biopsy of the lesion revealed a mass of clear epithelioid cells filling the lumen of a lymphatic vessel within the dermis (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10). Tumor histology demonstrated epithelioid cells with abundant clear cytoplasm and numerous vascular channels (B)(H&E, original magnification ×40).

Clear cell RCC, the most common renal malignancy, presents with metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis in 21% of patients. 1 An additional 20% of patients with localized disease develop metastases within several years of receiving a nephrectomy without adjuvant therapy, which is standard treatment for stage I to stage III disease. 1,2 Metastatic RCC most frequently targets the lungs, bone, liver, and brain, though virtually any organ can be involved. Cutaneous involvement is estimated to occur in 3.3% of RCC cases, 3 accounting for only 1.4% of cutaneous metastases overall. 4 The risk for developing cutaneous metastases is greatest within 3 years following nephrectomy. 3 However, our patient demonstrates that metastasis of RCC to skin can be long delayed (>5 years) despite an initial diagnosis of localized disease.

Cutaneous RCC classically presents as a painless firm papulonodule with a deep red or purple color due to its high vascularity. 4 Several retrospective studies have identified the scalp as the most frequent site of cutaneous involvement, followed by the chest, abdomen, and nephrectomy scar. 3,4 The differential diagnosis includes other vascular lesions such as pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, angiosarcoma, bacillary angiomatosis, and Kaposi sarcoma. Diagnosis usually is easily confirmed histologically. Proliferative nests of epithelioid cells with clear cell morphology are surrounded by delicately branching vessels referred to as chicken wire-like vasculature. Immunohistochemical studies demonstrate positivity for pan-cytokeratin, vimentin, and CD-10, and negativity for p63 and cytokeratins 5 and 6, helping to confirm the diagnosis in more challenging cases, especially when there is no known history of primary RCC. 5

If cutaneous metastasis of RCC is diagnosed, a chest and abdominal computed tomography scan as well as serum alkaline phosphatase test are warranted, as up to 90% of patients with RCC in the skin have additional lesions in at least 1 other site such as the lungs, bones, or liver. 3 Management of metastatic RCC includes surgical excision if a single metastasis is found and either immunotherapy with high-dose IL-2 or an anti-programmed cell death inhibitor. Patients with progressive disease also may receive targeted anti-VEGF inhibitors (eg, axitinib, pazopanib, sunitinib), which have been shown to increase progression-free survival in metastatic RCC. 6-8 Interestingly, some evidence suggests severely delayed recurrence of RCC (>5 years following nephrectomy) may predict better response to systemic therapy. 9

This case of severely delayed metastasis of RCC 8 years after nephrectomy raises the question of whether routine surveillance for RCC recurrence should continue beyond 5 years. It also underscores the need for further studies to determine the utility of postsurgical adjuvant therapy for localized disease (stages I-III). A randomized clinical trial showed no significant difference in disease-free survival when the multikinase inhibitors sunitinib and sorafenib were used as adjuvant therapy. 10 The randomized, placebo-controlled PROTECT trial showed no significant difference in disease-free survival between the VEGF inhibitor pazopanib and placebo when used as adjuvant therapy. 11 However, trials are ongoing to investigate a potential survival advantage of adjuvant therapy with the VEGF receptor inhibitor axitinib and the mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor everolimus.