Environmental Dermatology

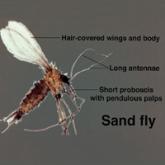

What’s Eating You? Sand Flies

As thousands of Americans descended upon Brazil for the Olympic games in the summer of 2016, the mosquito-borne Zika virus became a source of...

From the Department of Dermatology and Dermatologic Surgery, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

This article is the first of a 3-part series. The next part will appear in the April 2018 issue.

The images are in the public domain.

Correspondence: Dirk M. Elston, MD, Department of Dermatology and Dermatologic Surgery, Medical University of South Carolina, 135 Rutledge Ave, MSC 578, Charleston, SC 29425 (elstond@musc.edu).

The Ixodes tick is an important arthropod vector in the transmission of human disease. This 3-part review highlights the biology of the Ixodes tick and manifestations of related diseases. Part 1 addresses the Ixodes tick biology and life cycle; local reactions; and Lyme disease, the most prevalent of associated diseases. Part 2 will address human granulocytic anaplasmosis, babesiosis, Powassan virus infection, Borrelia miyamotoi disease, tick-borne encephalitis, and tick paralysis. Part 3 will address coinfection with multiple pathogens as well as methods of tick-bite prevention and tick removal.

Practice Points

Ticks are ectoparasitic hemophages that feed on mammals, reptiles, and birds. The Ixodidae family comprises the hard ticks. A hard dorsal plate, scutum, and capitulum that extends outward from the body are features that distinguish the hard tick. 1Ixodes is the largest genus of hard ticks, with more than 250 species localized in temperate climates.2 It has an inornate scutum and lacks festoons (Figure 1).1 The Ixodes ricinus species complex accounts for most species relevant to the spread of human disease (Figure 2), with Ixodes scapularis in the northeastern, north midwestern, and southern United States; Ixodes pacificus in western United States; I ricinus in Europe and North Africa; and Ixodes persulcatus in Russia and Asia. Ixodes holocyclus is endemic to Australia.3,4

Ixodes species progress through 4 life stages—egg, larvae, nymph, and adult—during their 3-host life cycle. Lifespan is 2 to 6 years, varying with environmental factors. A blood meal is required between each stage. Female ticks have a small scutum, allowing the abdomen to engorge during meals (Figure 3).

Larvae hatch in the early summer and remain dormant until the spring, emerging as a nymph. Following a blood meal, the nymph molts and reemerges as an adult in autumn. During autumn and winter, the female lays as many as 2000 eggs that emerge in early summer.5 Nymphs are small and easily undetected for the duration required for pathogen transmission, making nymphs the stage most likely to transmit disease.6

The majority of tick-borne diseases present from May to July, corresponding to nymph activity. Fewer cases present in the autumn and early spring because the adult female feeds during cooler months.7

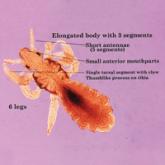

Larvae have 6 legs and are about the size of a sesame seed when engorged. Nymphs are slightly larger with 8 legs. Adults are largest and have 8 legs. Following a blood meal, the tick becomes engorged, increasing in size and lightening in color (Figure 3).1

Ticks are found in low-lying shrubs and tall grass as well as on the forest floor. They search for a host by detecting CO2, warmth, the smell of sweat, and the color white, prompting attachment.8 Habitats hospitable to Ixodes have expanded in the wake of climate, environmental, and socioeconomic changes, potentially contributing to the increasing incidence and expansion of zoonoses associated with this vector.9,10

As thousands of Americans descended upon Brazil for the Olympic games in the summer of 2016, the mosquito-borne Zika virus became a source of...

Dermacentor ticks are hard ticks found throughout most of North America and are easily identified by their large size, ornate scutum, and...

The head louse (Pediculus humanus capitis) is a blood-sucking arthropod of the suborder Anoplura. Infestation continues in epidemic...