Psoriasis is a T cell–mediated inflammatory disease that manifests as erythematous scaling plaques of the skin. In recent decades, our understanding of psoriasis has transformed from a disease isolated to the skin to a systemic disease impacting the overall health of those affected.

With recent elucidation of the pathways driving psoriasis, development of targeted therapies has resulted in an influx of options to the market. Navigating the options can seem overwhelming even to the seasoned clinician. Becoming familiar with a sound treatment approach during residency will create a foundation for biologic use in psoriasis patients throughout your career. Here we offer an approach to choosing biologic treatments based on individual patient characteristics, including disease severity, comorbidities, and ultimate treatment goals.

Immune Pathogenesis

Although the pathogenesis of psoriasis is complex and outside the scope of this article, we do recommend clinicians keep in mind the current understanding of pathways involved and ways our therapies alter them. Briefly, psoriasis is a T cell–mediated disease in which IL-12 and IL-23 released by activated dendritic cells activate T helper cells including TH1, TH17, and TH22. These cells produce additional cytokines, including IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α, IL-17, and IL-22, which propagate the immune response and lead to keratinocyte hyperproliferation. In general, psoriasis medications work by altering T-cell activation, effector cytokines, or cytokine receptors.

Comorbidities

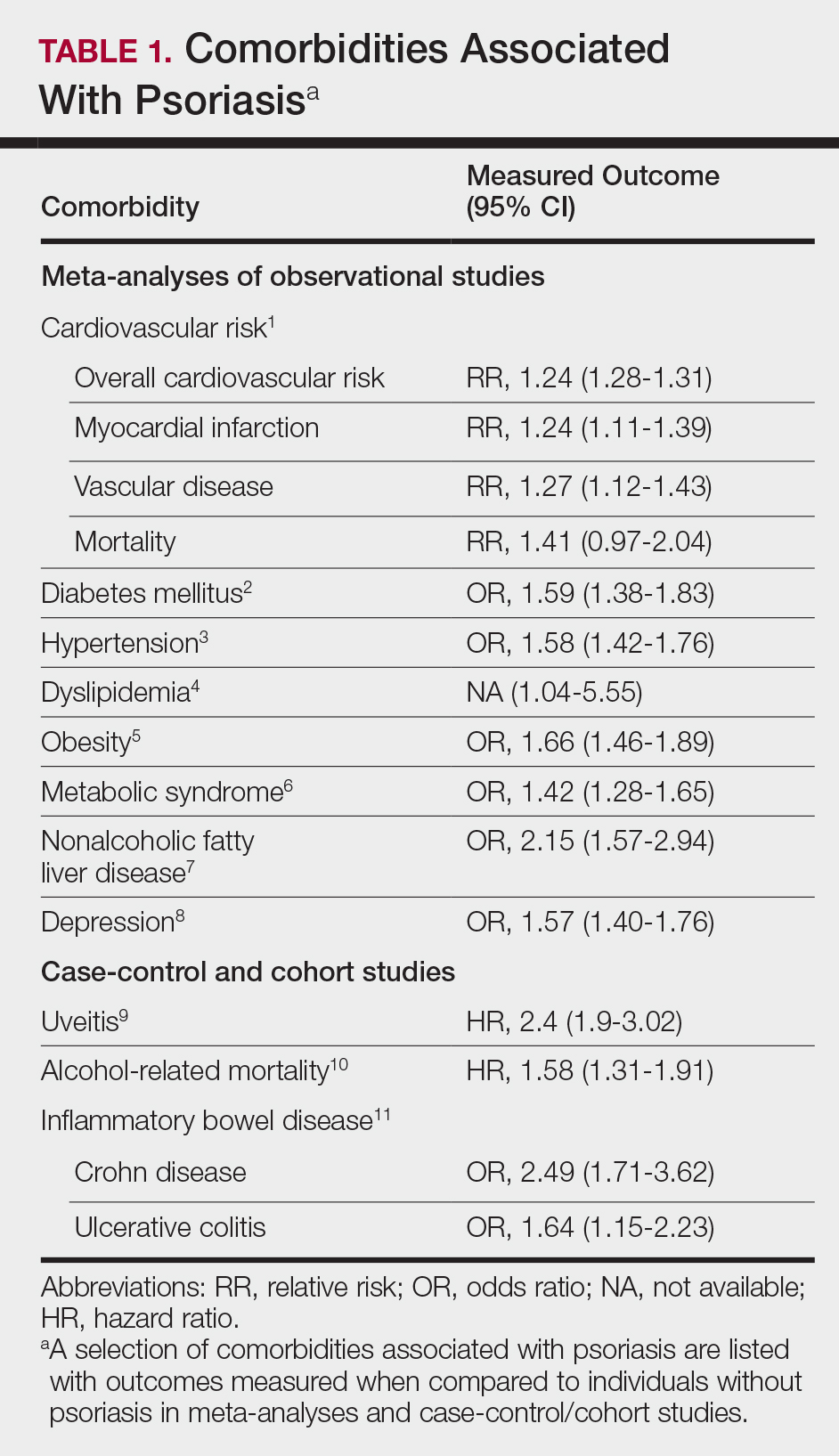

A targeted approach should take into consideration the immune dysregulation shared by psoriasis and associated comorbidities (Table 1). One goal of biologic treatments is to improve comorbidities when possible. At minimum, selected treatments should not exacerbate these conditions.

Treatment Goals

Establishing treatment goals can help shape patient expectations and provide a plan for clinicians. In 2017, the National Psoriasis Foundation published a treat-to-target approach using body surface area (BSA) measurements at baseline, 3 months, and then every 6 months after starting a new treatment.12 The target response is a decrease in psoriasis to 1% or less BSA at 3 months and to maintain this response when evaluated at 6-month intervals. Alternatively, a target of 3% BSA after 3 months is satisfactory if the patient improves by 75% BSA overall. If these targets are not met after 6 months, therapeutic alternatives can be considered.12

Biologic Treatment of Psoriasis

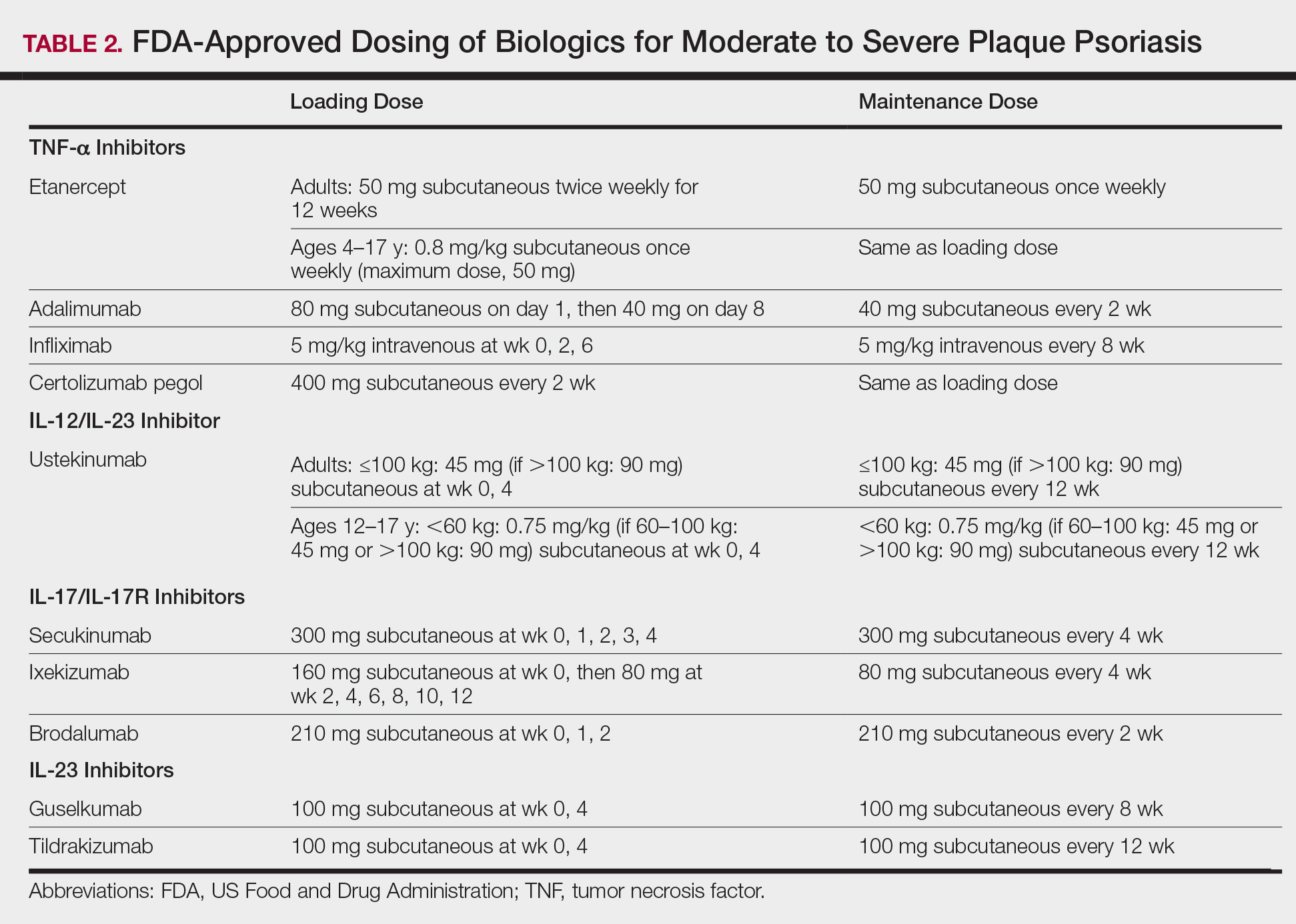

Treatment options for patients with psoriasis depend first on disease severity. Topicals and phototherapy are first line for mild to moderate disease. For moderate to severe disease, addition of systemic agents such as methotrexate, cyclosporine, or acitretin; small-molecular-weight immunomodulators such as apremilast; or biologic medications should be considered. Current biologics available for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis target TNF-α, IL-12/IL-23, IL-23, IL-17A, or IL-17A receptor.

TNF-α Inhibitors

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors have been available for treatment of autoimmune disease for nearly 20 years. These medications block either soluble cytokine or membrane-bound cytokine. All are given as subcutaneous injections, except for infliximab, which is a weight-based infusion.

Efficacy

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors are the first class to demonstrate long-term efficacy and safety in both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Etanercept was approved for adults with PsA in 2002 and psoriasis in 2004, and later for pediatric psoriasis (≥4 years of age) in 2016 (Table 2). Although etanercept has a sustained safety profile, the response rates are not as high as other anti–TNF-α inhibitors. Adalimumab is one of the most prescribed biologics, with a total of 10 indications at present, including PsA. Infliximab is an intravenous infusion that demonstrates a rapid and sustained response in most patients. The dose and dosing interval can be adjusted according to response. Certolizumab pegol was approved for PsA in 2013 and for psoriasis in 2018.

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors maintain efficacy well and work best when dosed continuously. Both neutralizing and nonneutralizing antibodies form with these agents. Neutralizing antibodies may contribute to decreased efficacy, particularly for the chimeric antibody infliximab. One approach to mitigate loss of efficacy is the short-term addition of low-dose methotrexate (eg, 7.5–15 mg weekly) for 3 to 6 months until response is recaptured.

Safety

To evaluate long-term safety, a multicenter prospective registry study (Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry [PSOLAR]) was initiated in 2007 to follow clinical outcomes. Data through 2013 showed no significant increase in rates of infection, malignancy, or major adverse cardiovascular events in more than 12,000 patients.13

Conflicting information exists in the literature regarding risk for malignancy with TNF-α inhibitors. One recent retrospective cohort study suggested a slightly increased risk for malignancies other than nonmelanoma skin cancers in patients on TNF-α inhibitors for more than 12 months (relative risk, 1.54).14 Reports of increased risk for cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas necessitate regular skin checks.15 A potential risk for lymphoma has been noted, though having psoriasis itself imparts an increased risk for Hodgkin and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.16

Reactivation of tuberculosis and hepatitis have been reported with TNF-α inhibition. Data suggest that infliximab may be associated with more serious infections.13

Demyelinating conditions such as multiple sclerosis have occurred de novo or worsened in patients on TNF-α inhibitors.17 Tumor necrosis factor α blockers should be avoided in patients with decompensated heart failure. Rare cases of liver enzyme elevation and cytopenia have been noted. Additionally, lupuslike syndromes, which are generally reversible upon discontinuation, have occurred in some patients.

Patient Selection

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors are the treatment of choice for patients with comorbid PsA. This class halts progression of joint destruction over time.18Select TNF-α inhibitors are indicated for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and are a preferred treatment in this patient population. Specifically, adalimumab and infliximab are approved for both Crohn disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis. Certolizumab pegol is approved for CD.

Tumor necrosis factor α is upregulated in obesity, cardiovascular disease, and atherosclerotic plaques. Evidence suggests that TNF-α blockers may lower cardiovascular risk over time.19 For patients with obesity, infliximab is a good option, as it is the only TNF-α inhibitor with weight-based dosing.

In patients with frequent infections or history of hepatitis C, etanercept has been the biologic most commonly used when no alternatives exist, in part due to its shorter half-life.