Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis (IGM) is rare during pregnancy; it typically is seen in women of childbearing potential from 6 months to 6 years postpartum.1 Because of a temporal association with breastfeeding, it is believed that hyperprolactinemia2 or an immune response to local lobular secretions might play a role in pathogenesis. Early misdiagnosis as bacterial mastitis is common, prompting multiple antibiotic regimens. When antibiotics fail, patients are worked up for inflammatory breast cancer, given the nonhealing breast nodules. Mammography, ultrasonography, and fine-needle aspiration often are unable to rule out carcinoma, warranting excisional biopsies of nodules. The patient is then referred to rheumatology for potential sarcoidosis or to dermatology for IGM. In either case, the workup should be similar, but additional history focused on behavior and medications is essential in suspected IGM, given the association with hyperprolactinemia.

Because IGM is rare, there are no randomized, placebo-controlled trials of treatment efficacy. In many cases, patients undergo complete mastectomy, which is curative but may be psychologically and physically impactful in young women. In some cases, high-dose corticosteroids have been successful; however, because the IGM process can last longer than 2 years, patients treated in this manner are exposed to steroid morbidities.1

We report 3 cases of IGM that add to the literature on possible contributing factors, clinical presentations, and treatments for this disease. We also demonstrate that appropriate trigger identification and steroid-sparing agents, specifically methotrexate, can be breast-saving as they can alleviate this debilitating condition, obviating the need for radical surgical intervention.

CASE REPORTS

Patient 1

A 40-year-old woman with a 4-year history of breastfeeding noted a grape-sized nodule on the left breast that grew to the size of a grapefruit after 2 weeks. Ulceration and drainage periodically occurred, forming pink plaques along the lateral aspects of the breast after healing. Her primary care provider suspected infectious mastitis; she was given an oral antibiotic (cephalexin) and intravenous antibiotics without improvement.

Imaging

Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging revealed a large, irregular, enhancing mass within the outer left breast (6.5 cm at greatest dimension) with additional surrounding amorphous enhancement highly suspicious for malignancy. There also were multiple prominent left axillary lymph nodes, with the largest demonstrating a cortical thickness of 8 mm.

Biopsy

Core breast biopsy showed benign tissue with fat necrosis. Fine-needle aspiration revealed few benign ductal cells and rare histiocytes; because these findings were nondiagnostic and cancer was still a consideration, the patient underwent excisional biopsy.

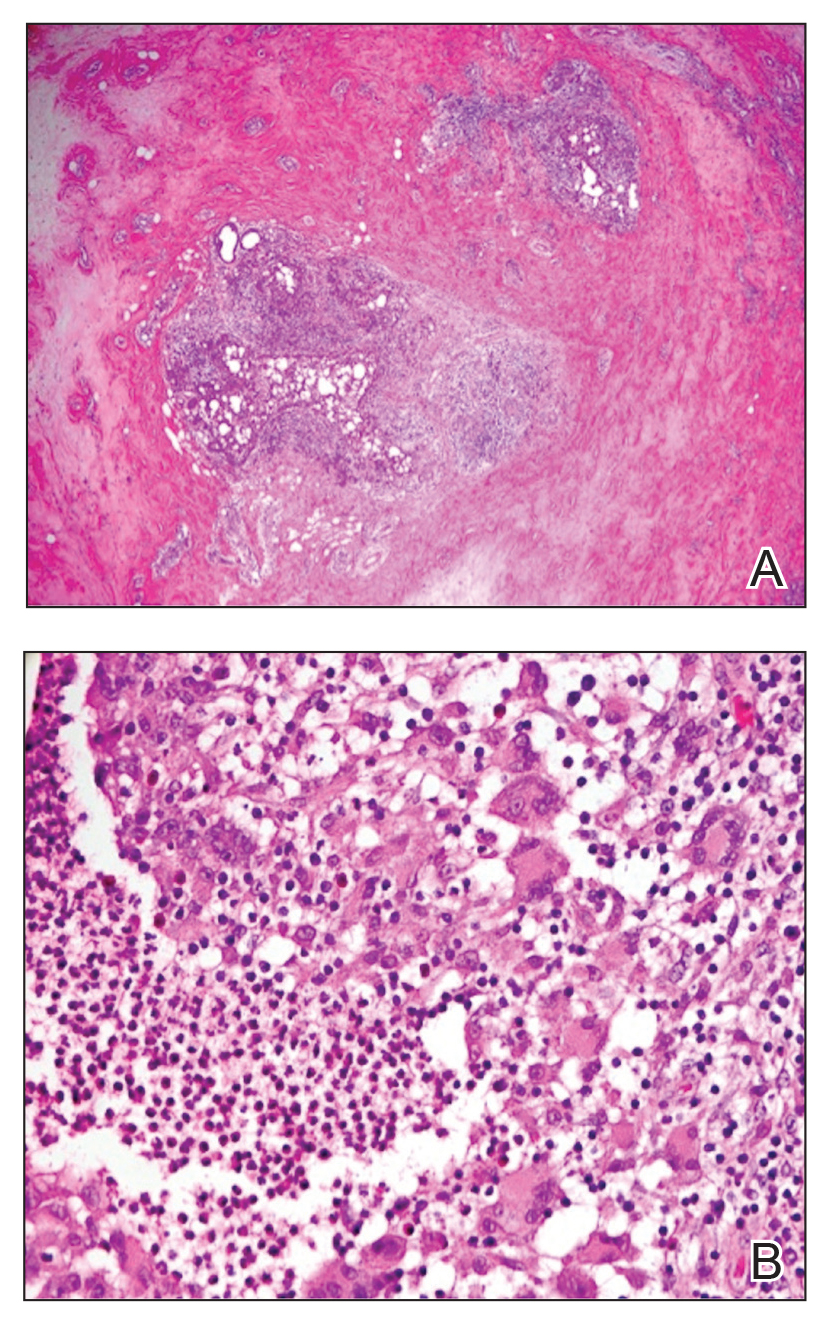

Histologic sections of breast tissue showed extensive lobulocentric inflammation comprising histiocytes and lymphocytes, with neutrophils admixed and forming microabscesses (Figure 1A). Multinucleated giant cells and single-cell necrosis were seen, but true caseous necrosis was absent (Figure 1B). Duct spaces often contained inflammatory cells or secretions. Special stains for fungal and acid-fast bacterial microorganisms were negative.

Referral to Dermatology

Granulomatous lobular mastitis was diagnosed, and the patient was referred to dermatology. On presentation to dermatology, the left breast showed a 6-cm area of firm induration and overlying peau d’orange change to the epidermis (Figure 2A). Based on pathologic analysis, she was worked up for a possible granulomatous etiology. Negative purified protein derivative (tuberculin)(PPD) and a normal chest radiograph ruled out tuberculosis. Normal chest radiography, serum Ca2+ and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) levels, and ophthalmology examination ruled out sarcoidosis.

The patient reported she continued breastfeeding her 4-year-old son. Additionally, she had been started on trazadone and buspirone for alcohol abuse recovery, then switched to and maintained on fluoxetine 1 year before developing these symptoms.

Buspirone, fluoxetine, and prolonged breastfeeding all contribute to hyperprolactinemia, a possible trigger of IGM. The patient was therefore advised to stop breastfeeding and to be switched from fluoxetine to a medication that would not increase the prolactin level. She did not require methotrexate treatment because her condition resolved rapidly after breastfeeding and fluoxetine were discontinued (Figure 2B).