To the Editor:

A 40-year-old white woman presented with a waxing and waning erythematous pruritic rash on the chest, back, and axillae of 3 years’ duration. The appearance of the rash coincided with an intentional weight loss of more than 100 lb, achieved through various diets, most recently a Paleolithic (paleo) diet that was high in protein; low in carbohydrates; and specifically restricted dairy, cereal grains, refined sugars, processed foods, white potatoes, salt, refined oils, and legumes.1 The patient had been monitoring blood glucose and ketone levels. Prior to presentation, she received various treatments including clotrimazole cream and topical steroids with no improvement.

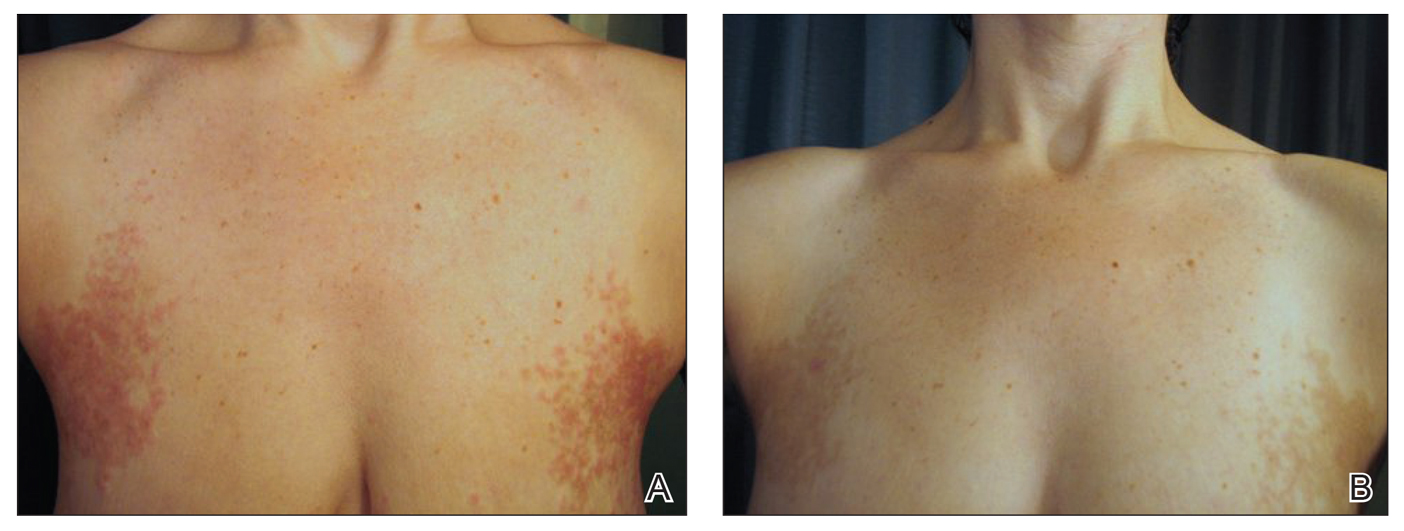

On physical examination, there were scaly, pink-red, reticulated papules and plaques coexisting with tan reticulated patches that were symmetrically distributed on the central back, lateral and central chest (Figure 1A), breasts, and inframammary areas. During the most severe flare-up, the blood ketones measured 1 mmol/L. There was no relevant medical history. She was of Spanish and Italian descent.

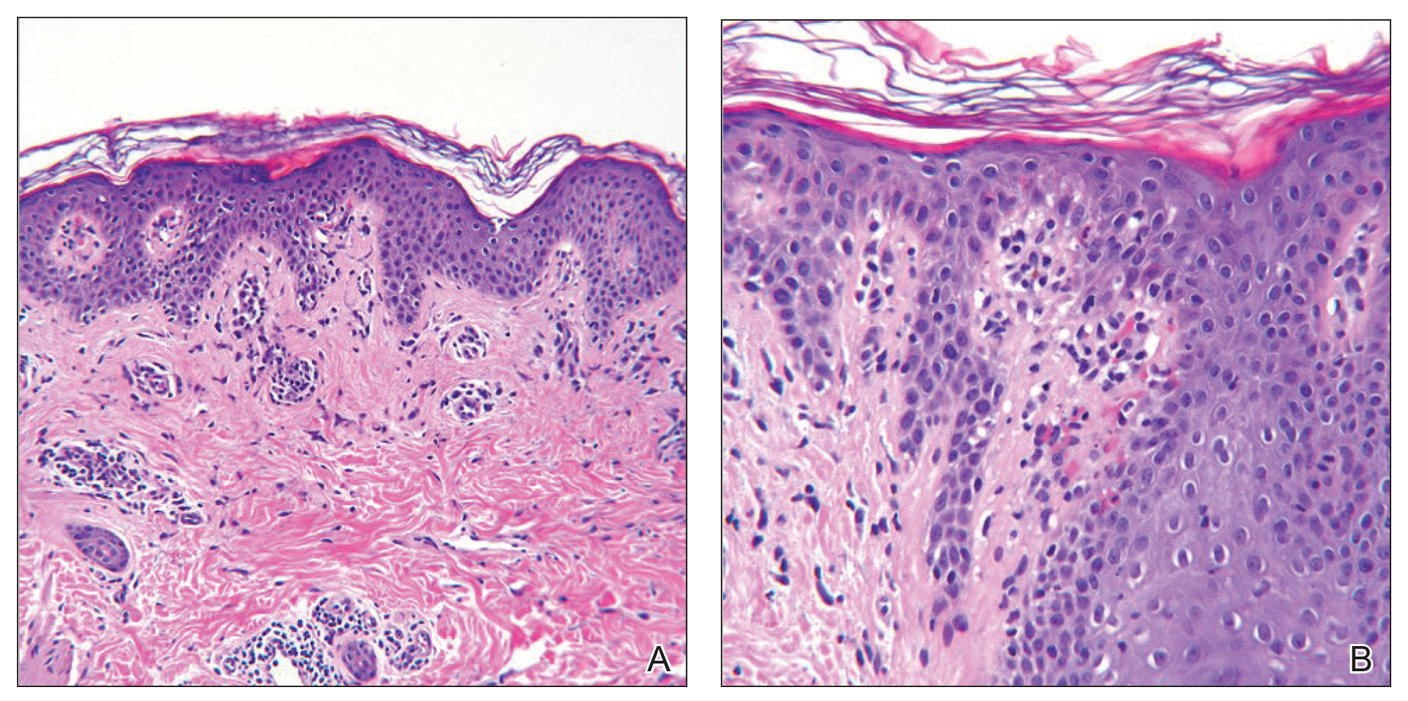

Histologic sections showed a sparse infiltrate of lymphocytes surrounding superficial dermal vessels and a mildly acanthotic epidermis with a focally parakeratotic stratum corneum (Figure 2A). Pigmentary incontinence and subtle interface changes were apparent, including rare necrotic keratinocytes (Figure 2B). No eosinophils or neutrophils were present.

Figure 2. A, Histopathology showed a lymphocytic perivascular infiltrate within the superficial dermis as well as an acanthotic and parakeratotic epidermis (H&E, original magnification ×100). B, Pigmentary incontinence and subtle interface changes were apparent, including rare necrotic keratinocytes (H&E, original magnification ×200).

After the initial presentation, carbohydrates were added back into her diet and both the ketosis and eruption remarkably resolved. When carbohydrate restriction was rechallenged, she again entered ketosis (0.5 mmol/L), followed by subsequent recurrence of the pruritic lesions. With re-introduction of carbohydrates, the eruption and ketosis once more resolved, leaving only postinflammatory reticulated hyperpigmentation (Figure 1B). Based on the clinical presentation, supportive histopathologic findings, and interesting response to ketones and diet modification, the patient was diagnosed with prurigo pigmentosa (PP).

Prurigo pigmentosa is a rare inflammatory dermatosis that was initially described in 1971 as “a peculiar pruriginous dermatosis with gross reticular pigmentation” by Nagashima et al.2 Prurigo pigmentosa is most frequently diagnosed in Japan, and since its discovery, it has been reported in more than 300 cases worldwide.2-4

Fewer than 50 non-Japanese cases have been reported, with the possibility of an additional ethnic predisposition among the Turkish and Sicilian populations, though only 6 cases have been reported in the United States.3-6 Prurigo pigmentosa tends to occur in the spring and summer months and is most common among young females, with a mean age of 24 years. The typical lesions of PP are symmetrically distributed on the trunk with a tendency to localize on the upper back, nape of the neck, and intermammary and inframammary regions. Eruptions have been reported to occur on additional areas; however, mucus membranes are always spared.6

Individual lesions differ in appearance depending on the stage of presentation and are categorized as early, fully developed, resolving, and late lesions.6 Pruritic macules and papules are present early in the disease state and resolve into crusted and/or scaly papules followed by pigmented macules. Early lesions tend to be intensely pruritic with signs of excoriation, while resolving lesions lack symptoms. Lesions last approximately 1 week but tend to reappear at the site where they were previously present, which allows for lesions of different ages to coexist, appearing in a reticular arrangement with hyperpigmented mottling lasting from a few weeks to months.6

Just as the clinical picture transpires rapidly within 1 week, so do the histopathologic findings.6 Early lesions are categorized by a superficial perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of neutrophils, spongiosis, ballooning, and necrotic keratinocytes. These early lesions are present for less than 48 hours, and these histopathologic findings are diagnostic of PP. Within 2 days, lymphocytes predominate in the dermal infiltrate, and a patchy lichenoid aspect is established in the fully developed lesion along with reticular and vacuolar alterations. Late lesions show a parakeratotic and hyperpigmented epidermis with melanophages present in the papillary and reticular dermis. At this last stage, the histopathologic features of PP are indistinguishable from any other disease that results in postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, making diagnosis difficult.6