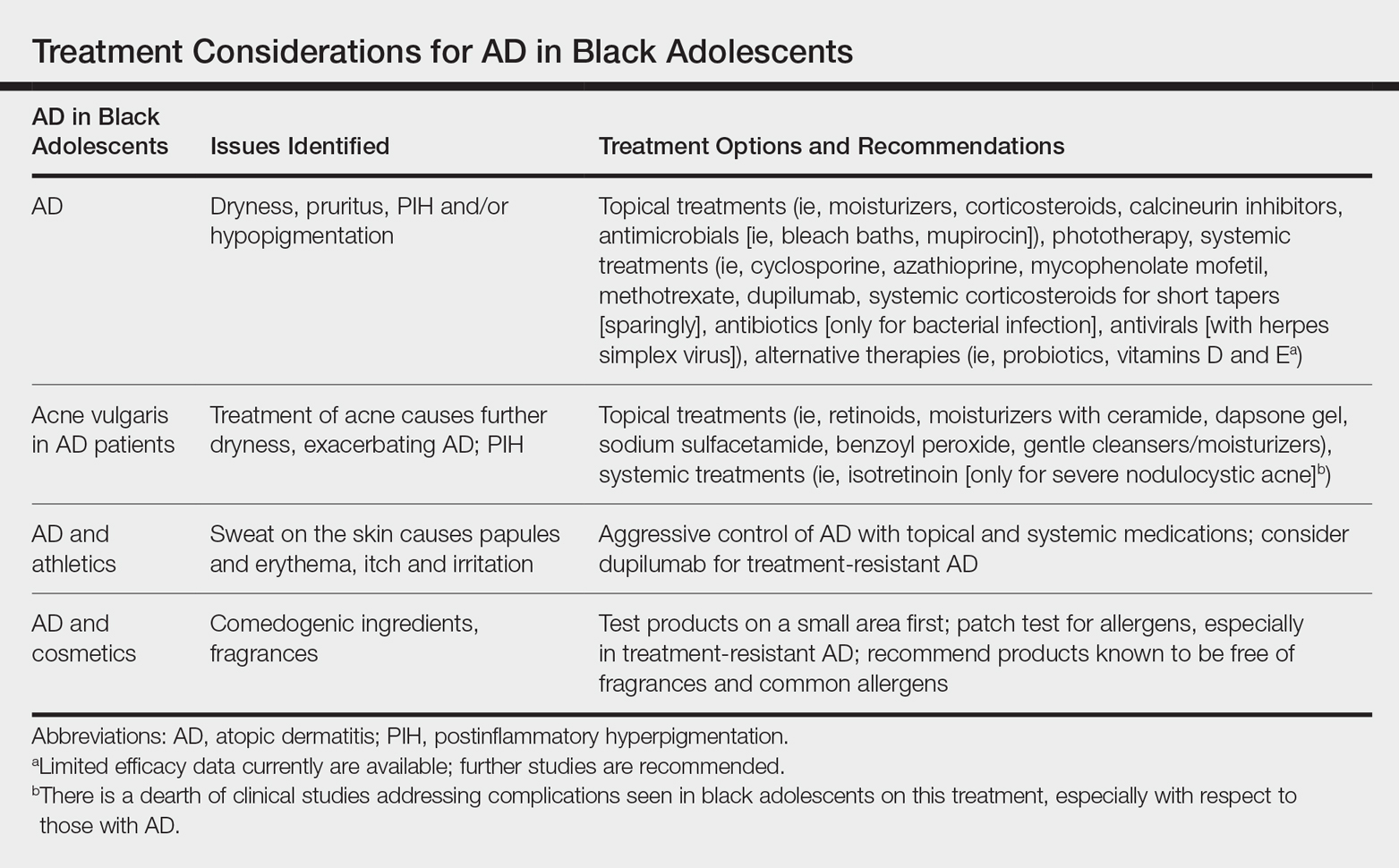

Data are limited on the management of atopic dermatitis (AD) in adolescents, particularly in patients with skin of color, making it important to identify factors that may improve AD management in this population. Comorbid conditions (eg, acne, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation [PIH]), extracurricular activities (eg, athletics), and experimentation with cosmetics in adolescents, all of which can undermine treatment efficacy and medication adherence, make it particularly challenging to devise a therapeutic regimen in this patient population. We review the management of AD in black adolescents, with special consideration of concomitant treatment of acne vulgaris (AV) as well as lifestyle and social choices (Table).

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Atopic dermatitis affects 13% to 25% of children and 2% to 10% of adults.1,2 Population‐based studies in the United States show a higher prevalence of AD in black children (19.3%) compared to European American (EA) children (16.1%).3,4

AD in Black Adolescents

Atopic dermatitis is a common skin condition that is defined as a chronic, pruritic, inflammatory dermatosis with recurrent scaling, papules, and plaques (Figure) that usually develop during infancy and early childhood.3 Although AD severity improves for some patients in adolescence, it can be a lifelong issue affecting performance in academic and occupational settings.5 One US study of 8015 children found that there are racial and ethnic disparities in school absences among children (age range, 2–17 years) with AD, with children with skin of color being absent more often than white children.6 The same study noted that black children had a 1.5-fold higher chance of being absent 6 days over a 6-month school period compared to white children. It is postulated that AD has a greater impact on quality of life (QOL) in children with skin of color, resulting in the increased number of school absences in this population.6

The origin of AD currently is thought to be complex and can involve skin barrier dysfunction, environmental factors, microbiome effects, genetic predisposition, and immune dysregulation.1,4 Atopic dermatitis is a heterogeneous disease with variations in the prevalence, genetic background, and immune activation patterns across racial groups.4 It is now understood to be an immune-mediated disease with multiple inflammatory pathways, with type 2–associated inflammation being a primary pathway. Patients with AD have strong helper T cell (TH2) activation, and black patients with AD have higher IgE serum levels as well as absent TH17/TH1 activation.4

Atopic dermatitis currently is seen as a defect of the epidermal barrier, with variable clinical manifestations and expressivity.7 Filaggrin is an epidermal barrier protein, encoded by the FLG gene, and plays a major role in barrier function by regulating pH and promoting hydration of the skin.4 Loss of function of the FLG gene is the most well-studied genetic risk factor for developing AD, and this mutation is seen in patients with more severe and persistent AD in addition to patients with more skin infections and allergic sensitizations.3,4 However, in the skin of color population, FLG mutations are 6 times less common than in the EA population, despite the fact that AD is more prevalent in patients of African descent.4 Therefore, the role of the FLG loss-of-function mutation and AD is not as well defined in black patients, and some researchers have found no association.3 The FLG loss-of-function mutation seems to play a smaller role in black patients than in EA patients, and other genes may be involved in skin barrier dysfunction.3,4 In a small study of patients with mild AD compared to nonaffected patients, those with AD had lower total ceramide levels in the stratum corneum of affected sites than normal skin sites in healthy individuals.8

Particular disturbances in the gut microbiome have the possibility of impacting the development of AD.9 Additionally, the development of AD may be influenced by the skin microbiome, which can change depending on body site, with fungal organisms thought to make up a large proportion of the microbiome of patients with AD. In patients with AD, there is a lack of microbial diversity and an overgrowth of Staphylococcus aureus.9