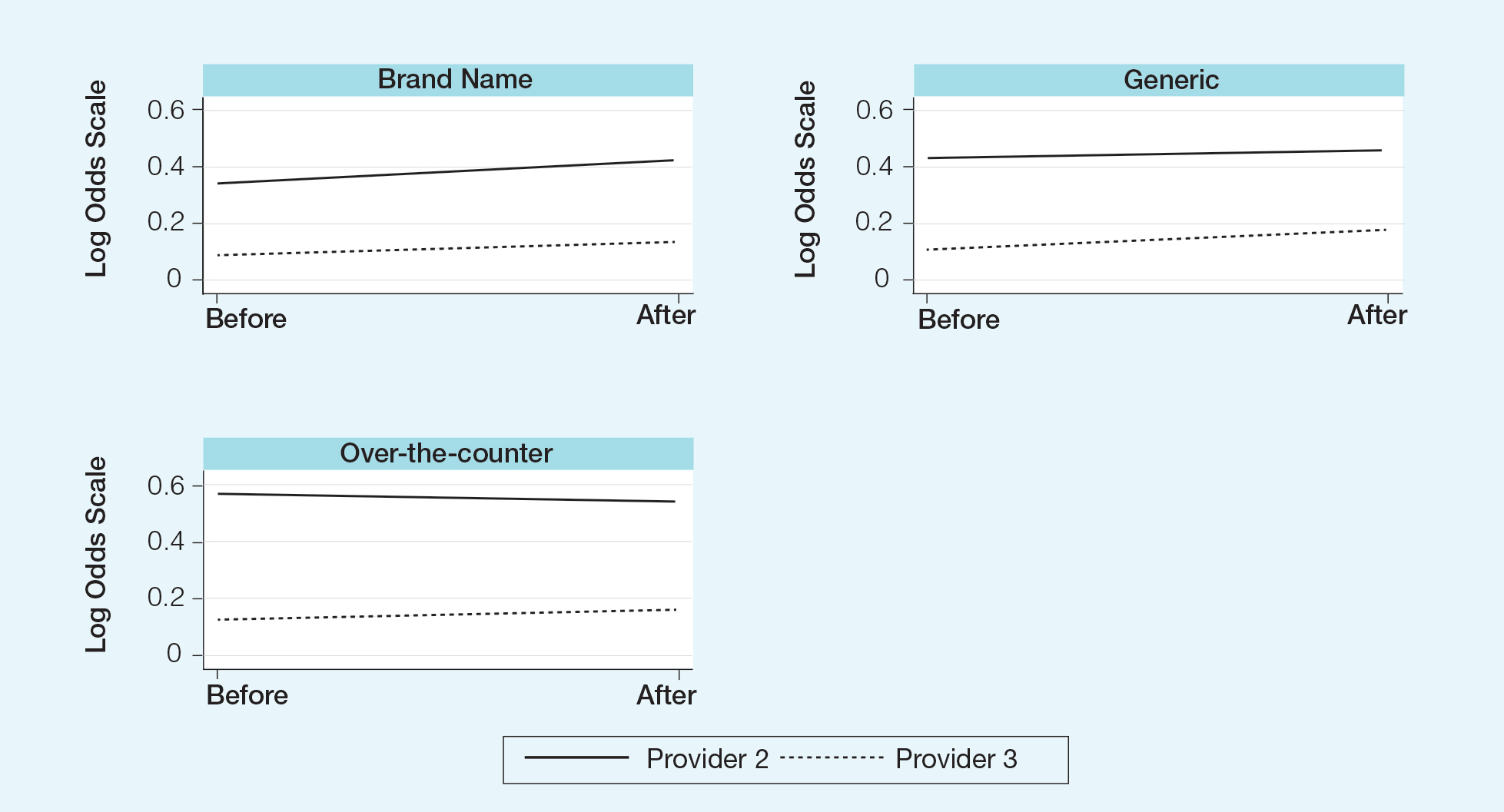

The mixed effects ordinal logistic regression model for the dependent variable—prescription type (branded, generic, or OTC)—showed an odds ratio (OR) of 1.27 for prescribing habits before and after the policy changes (OR, 1.27; 95% confidence interval, 0.97-1.67; P=.08) after accounting for provider and baseline characteristics. Despite the P value exceeding the predefined significance level, the confidence interval suggests anywhere from a 3% decrease, no change, and up to a 67% increase in postpolicy odds relative to the prepolicy odds, with a point estimate of a 27% increase in postpolicy odds over prepolicy odds. As an observational study, this suggests moderate evidence of a change based on the odds after the policy change relative to the odds before implementation (Figure).

Comment

Although some medical institutions are diligently working to limit the potential influence pharmaceutical companies have on physician prescribing habits,4,5,25 the effect on physician prescribing habits is only now being established.15 Prior studies12,19,21 have found evidence that medication samples may lead to overuse of brand-name medications, but these findings do not hold true for the USF dermatologists included in this study, perhaps due to the difference in pharmaceutical company interactions or physicians maintaining prior prescription habits that were unrelated to the policy. Although this study focused on policy changes for in-office samples, prior studies either included other forms of interaction21 or did not include samples.22

Pharmaceutical samples allow patients to try a medication before committing to a long-term course of treatment with a particular medication, which has utility for physicians and patients. Although brand-name prescriptions may cost more, a trial period may assist the patient in deciding whether the medication is worth purchasing. Furthermore, physicians may feel more comfortable prescribing a medication once the individual patient has demonstrated a benefit from the sample, which may be particularly true in a specialty such as dermatology in which many branded topical medications contain a different vehicle than generic formulations, resulting in notable variations in active medication delivery and efficacy. Given the higher cost of branded topical medications, proving efficacy in patients through samples can provide a useful tool to the physician to determine the need for a branded formulation.

The benefits described are subjective but should not be disregarded. Although Hurley et al19 found that the number of brand-name medications prescribed increases as more samples are given out, our study demonstrated that after eliminating medication samples, there was no significant difference in the percentage of brand-name medications prescribed compared to generic and OTC medications.

Physician education concerning the price of each brand-name medication prescribed in office may be one method of reducing the amount of such prescriptions. Physicians generally are uninformed of the cost of the medications being prescribed26 and may not recognize the financial burden one medication may have compared to its alternative. However, educating physicians will empower them to make the conscious decision to prefer or not prefer a brand-name medication. With some generic medications shown to have a difference in bioequivalence compared to their brand-name counterparts, a physician may find more success prescribing the brand-name medications, regardless of pharmaceutical company influence, which is an alternative solution to policy changes that eliminate samples entirely. Although this study found insufficient evidence that removing samples decreases brand-name medication prescriptions, it is imperative that solutions are established to reduce the country’s increasing burden of medical costs.

Possible shortfalls of this study include the short period of time between which prepolicy data and postpolicy data were collected. It is possible that providers did not have enough time to adjust their prescribing habits or that providers would not have changed a prescribing pattern or preference simply because of a policy change. Future studies could allow a time period greater than 2 years to compare prepolicy and postpolicy prescribing habits, or a future study might make comparisons of prescriber patterns at different institutions that have different policies. Another possible shortfall is that providers and patients were limited to those at the Department of Dermatology & Cutaneous Surgery at the USF Morsani COM. Although this study has found insufficient evidence of a difference in prescribing habits, it may be beneficial to conduct a larger study that encompasses multiple academic institutions with similar policy changes. Most importantly, this study only investigated the influence of in-office pharmaceutical samples on prescribing patterns. This study did not look at the many other ways in which providers may be influenced by pharmaceutical companies, which likely is a significant confounding variable in this study. Continued additional studies that specifically examine other methods through which providers may be influenced would be helpful in further examining the many ways in which physician prescription habits are influenced.

Conclusion

Changes in pharmaceutical policy in 2011 at USF Morsani COM specifically banned in-office samples. The totality of evidence in this study shows modest observational evidence of a change in the postpolicy odds relative to prepolicy odds, but the data also are compatible with no change between prescribing habits before and after the policy changes. Further study is needed to fully understand this relationship.