Immune checkpoint inhibitors are used for a variety of advanced malignancies, including melanoma, non–small cell lung cancer, urothelial cancer, and renal cell carcinoma. Anti–programmed cell death 1 (PD1) targeted therapies, such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab, are improving patient survival. This class of immunotherapy is revolutionary but is associated with autoimmune adverse effects. A rare but increasingly reported adverse effect of anti-PD1 therapy is bullous pemphigoid (BP), an autoimmune blistering disease directed against BP antigen 1 and BP antigen 2 in the basement membrane of the epidermis. Lopez et al1 reported that development of BP leads to discontinuation of immunotherapy in more than 70% of patients.

High clinical suspicion, early diagnosis, and proper management of immunotherapy-related BP are imperative for keeping patients on life-prolonging treatment. We present 3 cases of BP secondary to anti-PD1 immunotherapy in patients with melanoma or non–small cell lung cancer to highlight the diagnosis and treatment of BP as well as emphasize the importance of the dermatologist in the care of patients with immunotherapy-related skin disease.

Case Reports

Patient 1

A 72-year-old woman with metastatic BRAF-mutated melanoma from an unknown primary site presented with intensely pruritic papules on the back, chest, and extremities of 4 months’ duration. She described her symptoms as insidious in onset and refractory to clobetasol ointment, oral diphenhydramine, and over-the-counter anti-itch creams. The patient had been treated with oral dabrafenib 150 mg twice daily and trametinib 2 mg/d but was switched to pembrolizumab when the disease progressed. After 8 months, she had a complete radiologic response to pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks, which was discontinued in favor of observation 3 months prior to presentation to dermatology.

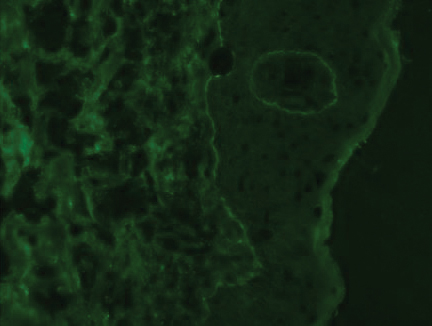

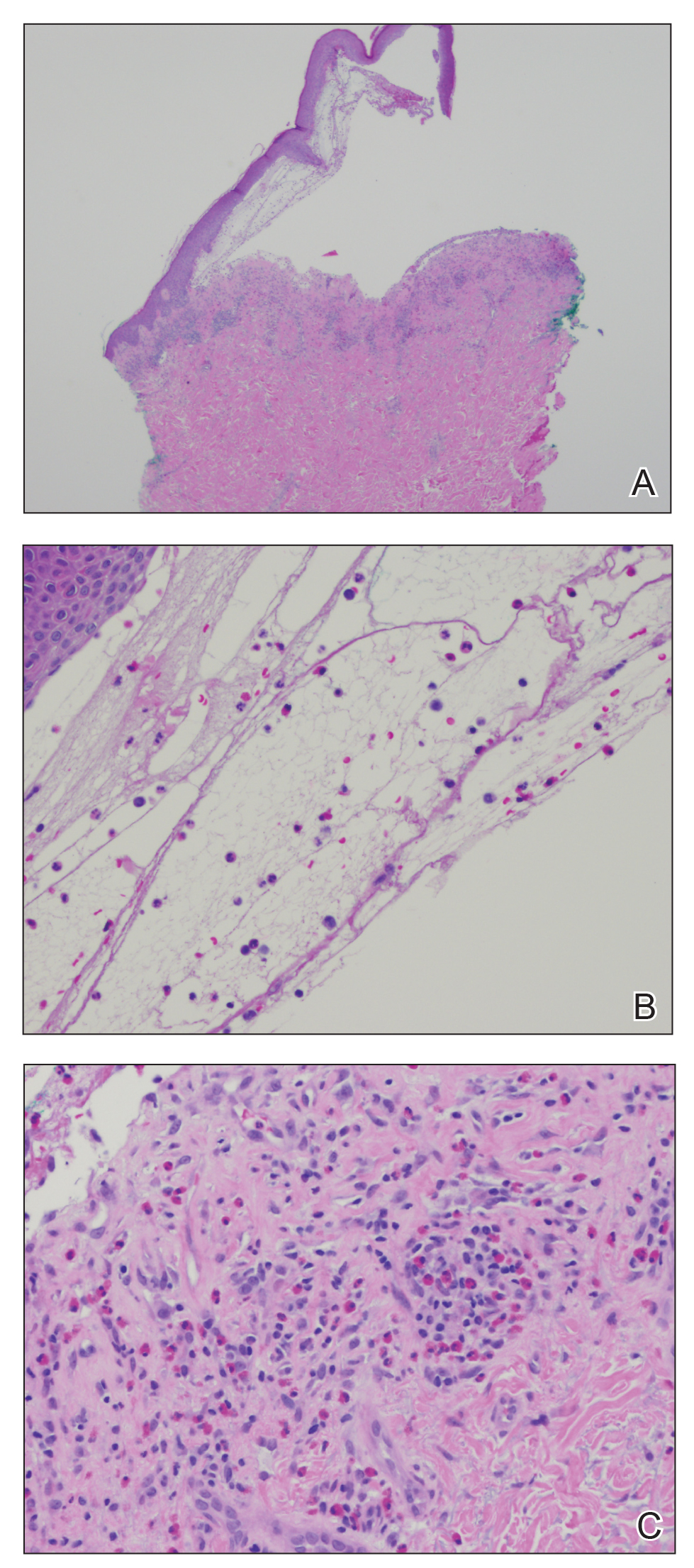

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed innumerable erythematous, excoriated, 2- to 4-mm, red papules diffusely scattered on the upper back, chest, abdomen, and thighs, with one 8×4-mm vesicle on the right side of the upper back (Figure 1). Discrete areas of depigmented macules, consistent with vitiligo, coalesced into patches on the legs, thighs, arms, and back. The patient was started on a 3-week oral prednisone taper for symptom relief. A hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)–stained punch biopsy of the back revealed a subepidermal split with eosinophils and a dense eosinophilic infiltrate in the dermis (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) studies from a specimen adjacent to the biopsy collected for H&E staining showed linear deposition of IgA, IgG, and C3 along the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 3). Histologic findings were consistent with BP.

Figure 2. A, Histopathology demonstrated a subepidermal split with a superficial inflammatory infiltrate (H&E, original magnification ×10). B, Higher-power view showed eosinophils within the subepidermal split (H&E, original magnification ×20). C, Dense eosinophilic infiltrate within the split, perivascular eosinophils, and scattered lymphocytes (H&E, original magnification ×20)

The patient was started on doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and clobetasol ointment 0.05% once daily to supplement the prednisone taper. At 3-week follow-up, she reported pruritus and a few erythematous macules but no new bullae. At 12 weeks, some papules persisted; however, the patient was averse to using systemic agents and decided that symptoms were adequately controlled with clobetasol ointment and oral doxycycline.

Because the patient currently remains in clinical and radiologic remission, anti-PD1 immune checkpoint inhibitors have not been restarted but remain an option for the future if disease recurs