Historically, there have been limited data available on the management of psoriasis in pregnancy. The most comprehensive discussion of treatment guidelines is from 2012.1 In the interim, many biologics have been approved for treating psoriasis, with slow accumulation of pregnancy safety data. The 2019 American Academy of Dermatology–National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines on biologics for psoriasis contain updated information but also highlight the paucity of pregnancy safety data.2 This gap is in part a consequence of the exclusion and disenrollment of pregnant women from clinical trials.3 Additionally, lack of detection through registries contributes; pregnancy capture in registries is low compared to the expected number of pregnancies estimated from US Census data.4 Despite these shortcomings, psoriasis patients who are already pregnant or are considering becoming pregnant frequently are encountered in practice and may need treatment. This article reviews the evidence on commonly used treatments for psoriasis in pregnancy.

Background

For many patients, psoriasis improves during pregnancy5,6 and becomes worse postpartum. In a prospective study, most patients reported improvement in pregnancy corresponding to a significant decrease in affected body surface area (P<.001) by 10 to 20 weeks’ gestation. Most patients also reported worsening of psoriasis postpartum; a significant increase in psoriatic body surface area (P=.001) was observed after delivery.7 Despite these findings, a considerable number of patients also experience stable disease or worsening of disease during pregnancy.

In addition to the maternal disease state, the issue of pregnancy outcomes is paramount. In the inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatology literature, it is established that uncontrolled disease is associated with poorer pregnancy outcomes.8-10 Guidelines vary among societies on the use of biologics in pregnancy generally (eTable 11,2,9,11-24), but some societies recommend systemic agents to achieve disease control during pregnancy.9,25

Assessing the potential interplay between disease severity and outcomes in pregnant women with psoriasis is further complicated by the slowly growing body of literature demonstrating that women with psoriasis have more comorbidities26 and worse pregnancy outcomes.27,28 Pregnant psoriasis patients are more likely to smoke, have depression, and be overweight or obese prior to pregnancy and are less likely to take prenatal vitamins.26 They also have an increased risk for cesarean birth, gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, and preeclampsia.28 In contrast to these prior studies, a systematic review revealed no risk for adverse outcomes in pregnant women with psoriasis.29

Assessment of Treatments for Psoriasis in Pregnancy

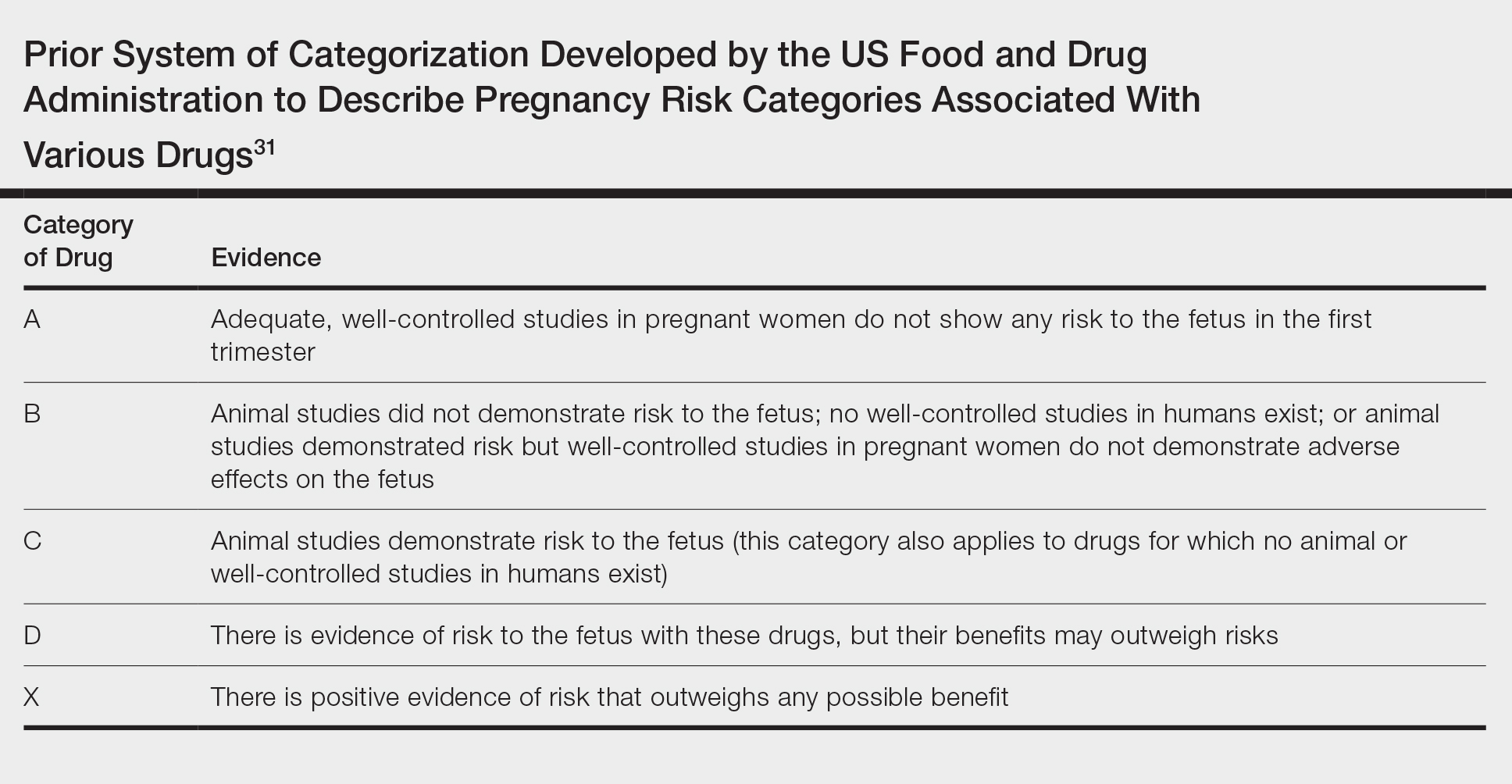

In light of these issues, treatment of psoriasis during pregnancy should be assessed from several vantage points. Of note, the US Food and Drug Administration changed its classification scheme in 2015 to a more narrative format called the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule.30 Prior classifications, however, provide a reasonable starting point for categorizing the safety of drugs (Table31). Importantly, time of exposure to systemic agents also matters; first-trimester exposure is more likely to affect embryogenesis, whereas second- and third-trimester exposures are more prone to affect other aspects of fetal growth. eTable 2 provides data on the use of oral and topical medications to treat psoriasis in pregnancy.1,8,22,32-45

Topical Agents

Topical steroids are largely understood to be reasonable treatment options, though consideration of potency, formulation, area of application, and use of occlusion is important.1,46 Risk for orofacial cleft has been noted with first-trimester topical steroid exposure, though a 2015 Cochrane review update determined that the relative risk of this association was not significantly elevated.32

The impact of topical calcipotriene and salicylic acid has not been studied in human pregnancies,1 but systemic absorption can occur for both. There is potential for vitamin D toxicity with calcipotriene46; consequently, use during pregnancy is not recommended.1,46 Some authors recommend against topical salicylic acid in pregnancy; others report that limited exposure is permissible.47 In fact, as salicylic acid commonly is found in over-the-counter acne products, many women of childbearing potential likely have quotidian exposure.

Preterm delivery and low birthweight have been reported with oral tacrolimus; however, risk with topical tacrolimus is thought to be low1 because the molecular size likely prohibits notable absorption.47 Evidence for the use of anthralin and coal tar also is scarce. First-trimester coal tar use should be avoided; subsequent use in pregnancy should be restricted given concern for adverse outcomes.1