Leishmaniasis is a neglected parasitic disease with an estimated annual incidence of 1.3 million cases, the majority of which manifest as cutaneous leishmaniasis.1 The cutaneous and mucosal forms demonstrate substantial global burden with morbidity and socioeconomic repercussions, while the visceral form is responsible for up to 30,000 deaths annually.2 Despite increasing prevalence in the United States, awareness and diagnosis remain relatively low.3 We describe 2 cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis in New England, United States, in travelers returning from Central America, both successfully treated with miltefosine. We also review prevention, diagnosis, and treatment options.

Case Reports

Patient 1

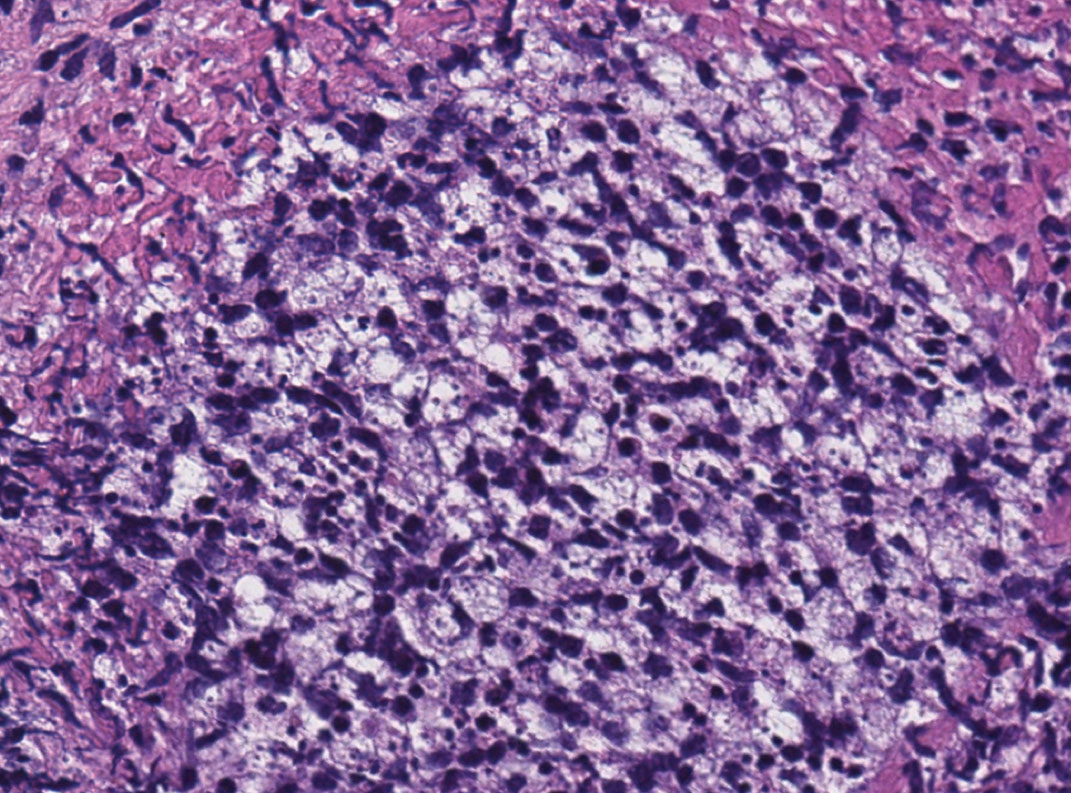

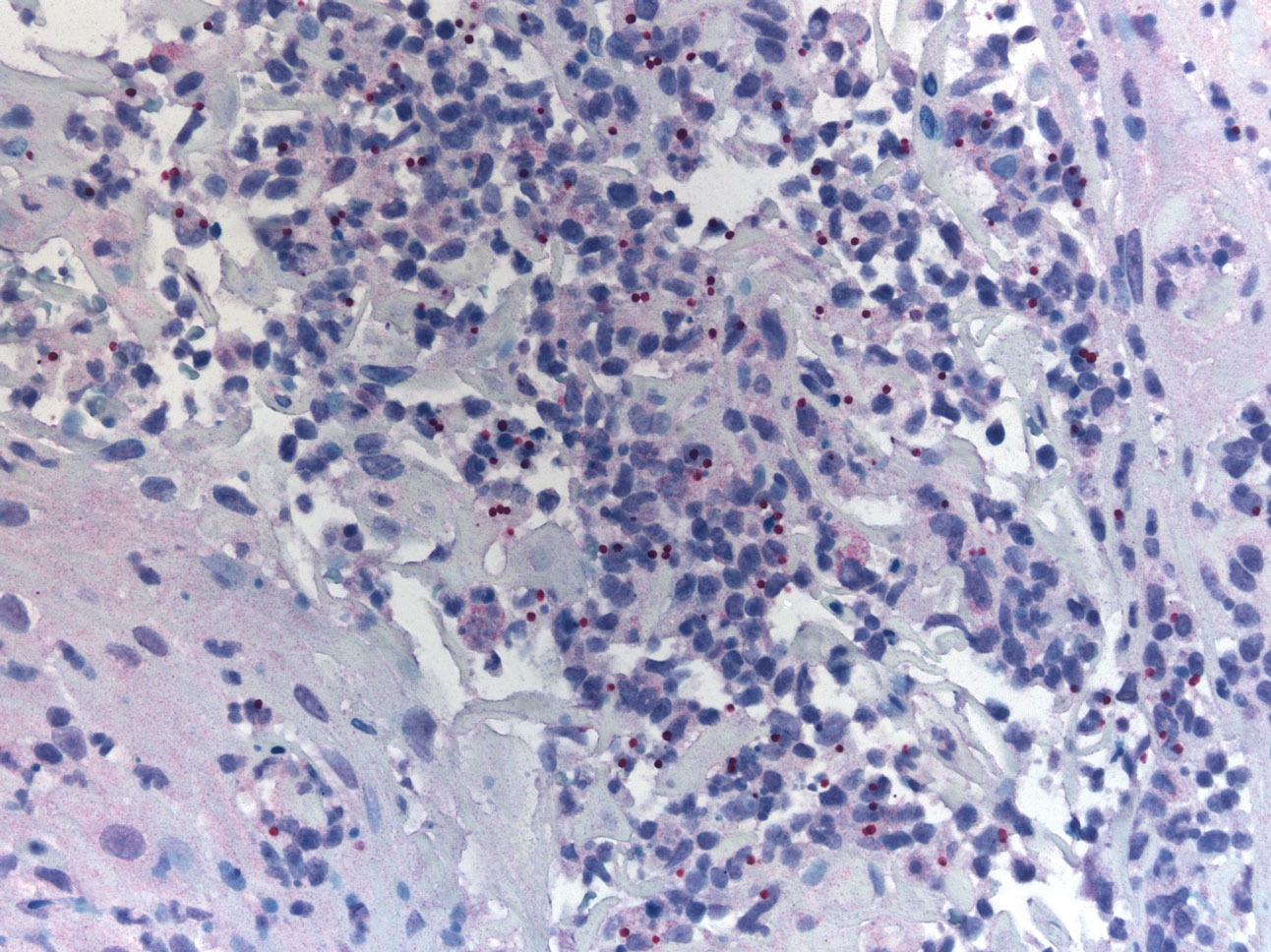

A 47-year-old woman presented with an enlarging, 2-cm, erythematous, ulcerated nodule on the right dorsal hand of 2 weeks’ duration with accompanying right epitrochlear lymphadenopathy (Figure 1A). She noticed the lesion 10 weeks after returning from Panama, where she had been photographing the jungle. Prior to the initial presentation to dermatology, salicylic acid wart remover, intramuscular ceftriaxone, and oral trimethoprim had failed to alleviate the lesion. Her laboratory results were notable for an elevated C-reactive protein level of 5.4 mg/L (reference range, ≤4.9 mg/L). A punch biopsy demonstrated pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with diffuse dermal lymphohistiocytic inflammation and small intracytoplasmic structures within histiocytes consistent with leishmaniasis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry was consistent with leishmaniasis (Figure 3), and polymerase chain reaction performed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) identified the pathogen as Leishmania braziliensis.

Patient 2

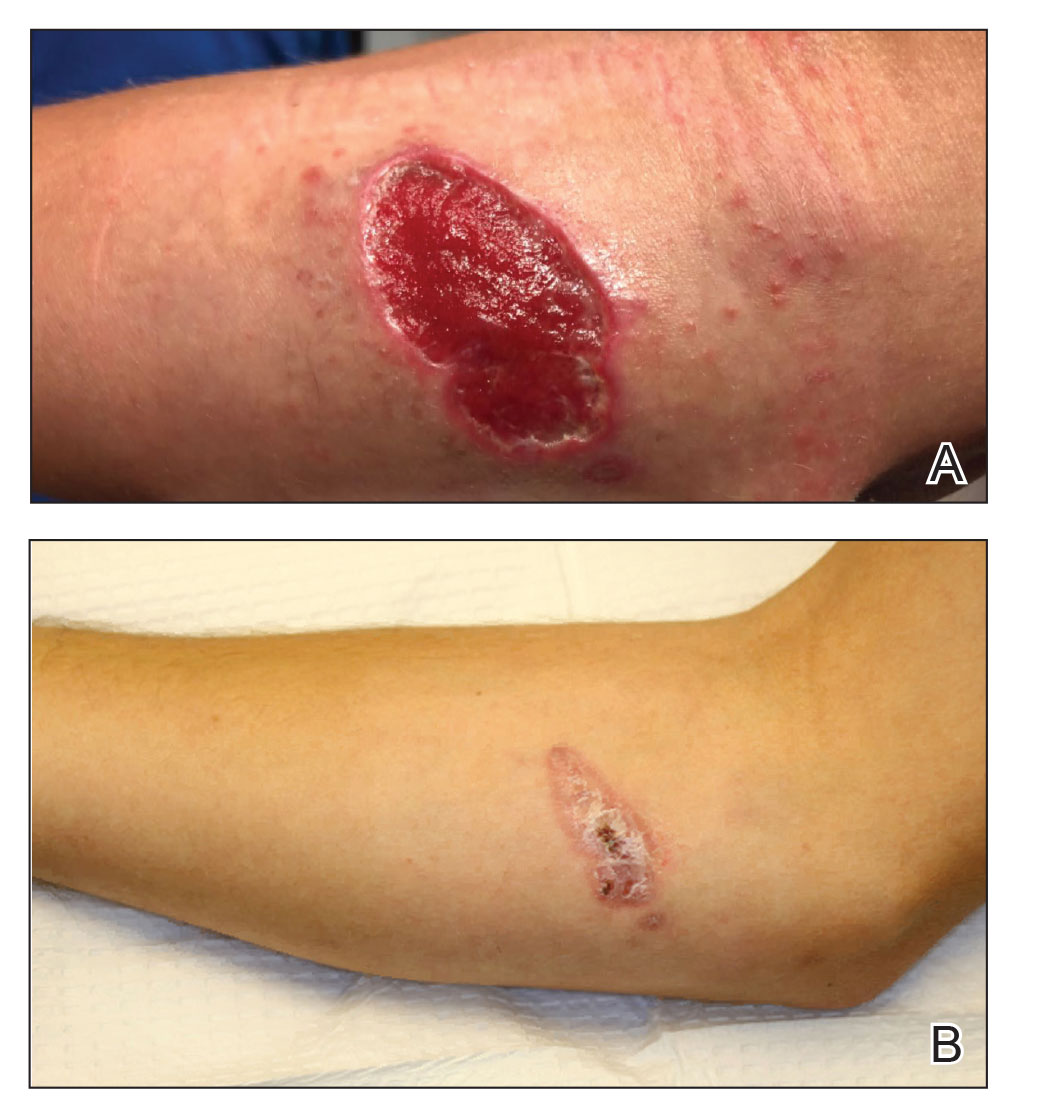

An 18-year-old man presented with an enlarging, well-delineated, tender ulcer of 6 weeks’ duration measuring 2.5×2 cm with an erythematous and edematous border on the right medial forearm with associated epitrochlear lymphadenopathy (Figure 4). Nine weeks prior to initial presentation, he had returned from a 3-month outdoor adventure trip to the Florida Keys, Costa Rica, and Panama. He had used bug repellent intermittently, slept under a bug net, and did not recall any trauma or bite at the ulcer site. Biopsy and tissue culture were obtained, and histopathology demonstrated an ulcer with a dense dermal lymphogranulomatous infiltrate and intracytoplasmic organisms consistent with leishmaniasis. Polymerase chain reaction by the CDC identified the pathogen as Leishmania panamensis.

Treatment

Both patients were prescribed oral miltefosine 50 mg twice daily for 28 days. Patient 1 initiated treatment 1 month after lesion onset, and patient 2 initiated treatment 2.5 months after initial presentation. Both patients had noticeable clinical improvement within 21 days of starting treatment, with lesions diminishing in size and lymphadenopathy resolving. Within 2 months of treatment, patient 1’s ulcer completely resolved with only postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (Figure 1B), while patient 2’s ulcer was noticeably smaller and shallower compared with its peak size of 4.2×2.4 cm (Figure 4B). Miltefosine was well tolerated by both patients; emesis resolved with ondansetron in patient 1 and spontaneously in patient 2, who had asymptomatic temporary hyperkalemia of 5.2 mmol/L (reference range, 3.5–5.0 mmol/L).

Comment

Epidemiology and Prevention

Risk factors for leishmaniasis include weak immunity, poverty, poor housing, poor sanitation, malnutrition, urbanization, climate change, and human migration.4 Our patients were most directly affected by travel to locations where leishmaniasis is endemic. Despite an increasing prevalence of endemic leishmaniasis and new animal hosts in the southern United States, most patients diagnosed in the United States are infected abroad by Leishmania mexicana and L braziliensis, both cutaneous New World species.3 Our patients were infected by species within the New World subgenus Viannia that have potential for mucocutaneous spread.4

Because there is no chemoprophylaxis or acquired active immunity such as vaccines that can mitigate the risk for leishmaniasis, public health efforts focus on preventive measures. Although difficult to achieve, avoidance of the phlebotomine sand fly species that transmit the obligate intracellular Leishmania parasite is a most effective measure.4 Travelers entering geographic regions with higher risk for leishmaniasis should be aware of the inherent risk and determine which methods of prevention, such as N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET) insecticides or permethrin-treated protective clothing, are most feasible. Although higher concentrations of DEET provide longer protection, the effectiveness tends to plateau at approximately 50%.5