As part of the 50th anniversary of Dermatology News, it is intriguing to think about where a time machine journey 5 decades back would find the field of pediatric dermatology, and to assess the changes in the specialty during the time that Dermatology News (operating then as “Skin & Allergy News”) has been reporting on innovations and changes in the practice of dermatology.

So, starting . It was not until 3 years later, in October 1973 in Mexico City, that the first international symposium on Pediatric Dermatology was held, and the International Society for Pediatric Dermatology was founded. I reached out to Andrew Margileth, MD, 100 years old this past July, and still active voluntary faculty in pediatric dermatology at the University of Miami, to help me “reach back” to those days. Dr. Margileth commented on how the first symposium was “brilliantly orchestrated by Ramon Ruiz-Maldonado,” from the National Institute of Paediatrics in Mexico, and that it was his “Aha moment for future practice!” That meeting spurred discussions on the development of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology the next year, with Alvin Jacobs, MD; Samuel Weinberg, MD; Nancy Esterly, MD; Sidney Hurwitz, MD; William Weston, MD; and Coleman Jacobson, MD, as some of the initial “founding mothers and fathers,” and the society was officially established in 1975.

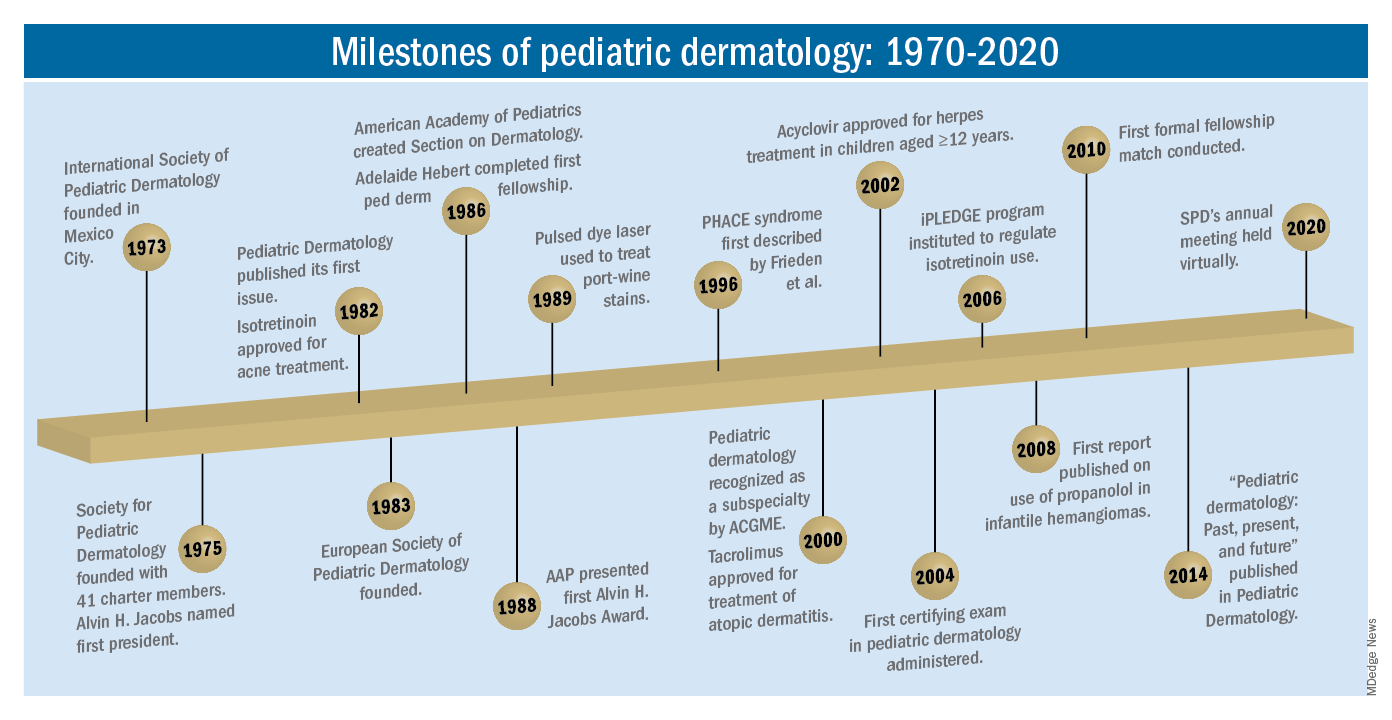

The field of pediatric dermatology was fairly “infantile” 50 years ago, with few practitioners. But the early leaders in the field recognized that up to 30% of pediatric primary care visits included skin problems, and that there was limited training for dermatologists, as well as pediatricians, about skin diseases in children. There were clearly clinical and educational needs to establish a subspecialty of pediatric dermatology, and over the next 1-2 decades, the field expanded. The journal Pediatric Dermatology was established (in 1982), the Section on Dermatology was established by the American Academy of Pediatrics (in 1986), and fellowship programs were launched at select academic centers. And it was 30 years into our timeline before the formal subspecialty of pediatric dermatology was established through the American Board of Dermatology (2000).

The field of pediatric dermatology has evolved and matured rapidly. Standard reference textbooks have been developed in the United States and around the world (and of course, online). Pediatric dermatology is an essential part of the core curriculum for dermatologist trainees. Organizations promoting pediatric research have developed to influence basic, translational, and clinical research in conditions in neonates through adolescents, such as the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance (PeDRA). And meetings throughout the world now feature pediatric dermatology sessions and help to spread the advances in the diagnosis and management of pediatric skin disorders.

The practice of pediatric dermatology: How has it changed?

It is beyond the scope of this article to try to comprehensively review all of the changes in pediatric dermatology practice. But review of the evolution of a few disease states (choices influenced by my discussions with my 100-year old history guide, Dr. Margileth) displays examples of where we have been, and where we are going in our next 5, 10, or 50 years.

Hemangiomas and vascular malformations

Some of the first natural history studies on hemangiomas were done in the early 1960s, establishing that standard cutaneous hemangiomas had a typical clinical course of fairly rapid growth, plateau, and involution over time. Of interest, the hallmark article’s first author was Dr. Margileth, published in 1965 in JAMA!.This was still at a time when the identification of hemangiomas of infancy (or “HOI” as we say in the trade) was confused with vascular malformations, and no one had recognized the distinct variant tumors such as rapidly involuting and noninvoluting congenital hemangiomas (RICHs or NICHs), tufted angiomas, or hemangioendotheliomas. PHACE syndrome was not yet described (that was done in 1996 by Ilona Frieden, MD, and colleagues). And for a time, hemangiomas were treated with x-rays, before the negative impact of such radiation was acknowledged. It seems that, as a consequence of the use of x-ray therapy and as a backlash from the radiation therapy side effects and potential toxicities, even deforming and functionally significant lesions were “followed clinically” for natural involution, with a sensibility that doing nothing might be better than doing the wrong thing.

Over the next 15 years, the recognition of functionally significant hemangiomas, deformation associated with their proliferation, and the recognition of PHACE syndrome made hemangiomas of infancy an area of concern, with systemic steroids and occasionally chemotherapeutic agents (such as vincristine) being used for problematic lesions.

It has now been 12 years since the work of Christine Léauté-Labrèze, MD, et al., from the University of Bordeaux (France), led to the breakthrough of propranolol for hemangioma treatment, profoundly changing hemangioma management to an incredibly effective medical therapy extensively studied, tested in formal clinical trials, and approved by regulatory authorities. And how intriguing that this was pursued after the chance (but skilled) observation that a child who developed hypertension as a side effect of systemic steroids for nasal hemangioma treatment was prescribed propranolol for the hypertension and had his nasal hemangioma rapidly shrink, with a response superior and much quicker than that to corticosteroids.

The evolution of management of hemangiomas has another story within it, that of collaborative research. The Hemangioma Investigator Group was formed to take a collaborative approach to characterize and study hemangiomas and related tumors. Beginning with energetic, insightful pediatric dermatologists and little funding, they changed our knowledge base of how hemangiomas present, the risk factors for their development, and the characteristics and multiple organ findings associated with PHACE and other syndromic hemangiomas. Our knowledge of these lesions is now evidence based and broad, and the impact on care tremendous! The HIG has also influenced the practice of pediatricians and other specialists, including otorhinolaryngologists, hematologist/oncologists, and surgeons, is partnering with advocacy groups to support patients and families, and is helping guide patients and families to contribute to ongoing research.

Vascular malformations (VM) reflect an incredible change in our understanding of the developmental pathways and pathophysiology of blood vessel tumors, and, in fact, birthmarks other than vascular lesions! First, important work separated out hemangiomas of infancy and hemangiomalike tumors from vascular malformations, with the thought being that hemangiomas had a rapid growth phase, often arising from lesions that were minimally evident or not evident at birth, unlike malformations, which were “programing errors,” all present at birth and expected to be fairly static with proportionate growth over a lifetime. Approaches to vascular malformations were limited to sclerotherapy, laser, and/or surgery. While this general schema of classification is still useful, our sense of the “why and how” of vascular malformations is remarkably different. Vascular malformations – still usefully subdivided into capillary, lymphatic, venous arteriovenous, or mixed malformations – are mostly associated with inherited or somatic mutations. Mutations are most commonly found in two signal pathways: RAS/MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways, with specific sets of mutations seen in both localized and multifocal lesions, with or without overgrowth or other systemic anomalies. The discovery of specific mutations has led to the possibility of small-molecule inhibitors, many already existing as anticancer drugs, being utilized as targeted therapies for VM.

And similar advances in understanding of other birthmarks, with or without syndromic features, are being made steadily. The mutations in congenital melanocytic nevi, epidermal nevi, acquired tumors (pilomatricomas), and other lesions, along with steady epidemiologic, translational, and clinical work, evolves our knowledge and potential therapies.