The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

On examination, the patient had multiple punched-out ulcers with indurated borders and surrounding erythema arranged in a sporotrichoid pattern from the left forearm to the left lateral chest (Figure 1).

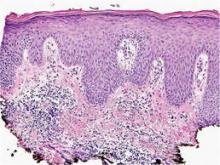

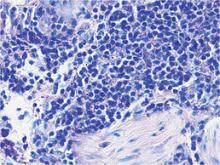

Bacterial culture of a tissue specimen was negative, and tissue fungal culture failed to grow any organisms. Serological studies included a complete blood cell count with differential, a chemistry panel, and liver function tests, which were all unremarkable. Coccidioidomycosis and human immunodefi-ciency virus antibodies were negative. A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained and sent to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology for review. Histopathologic examination revealed marked inflammation with ill-formed noncaseating granulomas and focal ulceration, necrosis in the deep dermis, and both intra-cellular and extracellular amastigotes within areas of necrosis (Figures 2 and 3).

The rise in the number of cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the United States, particularly in the veteran population, can be attributed to the recent conflicts in the Middle East and Afghanistan. Infection with Leishmania species can result in a variety of clinical presentations, ranging from localized, self-limited cutaneous lesions to a life-threatening infection with visceral involvement.1 Additionally, the host immune response is variable. This variation in clinical presentation and disease progression explains why there is no single best treatment identified for leishmaniasis to date.

The clinical pattern of spread along the lymphatics in this patient is unique. The differential diagnosis of lesions with sporotrichoid spread includes Mycobacterium marinum and other atypical mycobacterial infections, Sporothrix schenckii, nocardiosis, leishmaniasis, coccidioidomycosis, tularemia, cat scratch disease, anthrax, chromoblastomycosis, pyogenic bacteria, and other fungal or bacterial infections. With such a broad differential diagnosis, histologic confirmation is paramount.

The most widely used pharmacotherapy for leishmaniasis is with pentavalent antimony compounds, which have been studied in randomized controlled trials for leishmaniasis more than any other drug.2 These antimony compounds are associated with a large spectrum of clinical adverse events, and there is increasing evidence for emerging parasite resistance to the antimonies.3-5 Historically, amphotericin B was considered a second-line treatment of leishmaniasis due to its systemic toxicity.6 However, this treatment has come back into favor due to its newer, more tolerable, lipid-associated formulation.

Our patient was treated with intravenous liposomal amphotericin B at a dosage of 3 mg/kg daily for days 1 to 5, then again on days 14 and 21. He tolerated the therapeutic regimen without difficulty or adverse effects. The ulcers eventually became smaller and ceased to weep, fully healing over a course of several months.