To read a digital version of the print supplement, click here.

Deborah Friedman, MD, MPH

Professor, Departments of Neurology and Ophthalmology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center

To gain a full understanding of the challenges faced by neurologists, headache specialists, and other clinicians when managing triggers that prompt migraine headache attacks, consider the case of Lola H, a 35-year-old woman with a history of recurrent headaches that was diagnosed 12 months earlier as migraine without aura. Lola is taking oral sumatriptan, 100 mg, for acute migraine episodes, which she reports experiencing 3 or 4 times a month. She also has up to 3 headaches a week that are less severe. Lola’s insurance carrier limits the number of sumatriptan tablets covered in a month, forcing her use the medication only when she has severe headaches. However, the rationing strategy adds stress to her life that could be contributing to additional headache episodes.

Lola raised this issue during a recent visit with her neurologist, at which time she also presented a lengthy list of things she felt were triggering her attacks: stress, her menstrual cycle, chocolate, the odor of gasoline, and the weather, among other potential causes. Regarding the weather, she reported experiencing headaches—sometimes severe—whenever barometric pressure drops. Lola told her clinician that she believes she has gained control of 2 triggers—chocolate and gasoline fumes—through avoidance. She no longer consumes chocolate and other sweets and relies on family members and friends to fill her automobile fuel tank. However, Lola said she cannot control other triggers and needs her clinician’s help. She insists on leaving the appointment with answers she feels satisfied with. More than anything, she wants to feel secure that she has enough medication to meet her needs. (We will reveal how Lola fared later in this article.)

Heterogeneity of triggers: A daunting challenge

Lola’s circumstances are not uncommon among the nearly 40 million migraine sufferers in the United States.1 For clinicians seeking to better understand how potential triggers cause migraine attacks, it is important to appreciate the fine lines that exist between (1) perceived triggers, (2) their apparent frequency and strength, (3) patients’ efforts to control these factors, and (4) the distinction between real migraine triggers and premonitory symptoms. Moreover, recognizing how each of these 4 issues influence the patient’s experience enables the clinician to optimally manage individuals who experience migraine headache.

A diverse array of potential stimuli

Perhaps the most daunting challenge when trying to uncover what is triggering Lola’s and other migraine patients’ headaches is the realization that triggers and perceived triggers comprise a diverse array of potential stimuli. A meta-analysis of 85 studies conducted over a 60-year period and involving more than 27,000 participants revealed 420 unique headache triggers categorized to 1 of 15 categories.2 Characterizing these triggers as vastly heterogenous is an understatement, considering that they include factors such as raising the arms overhead, sneezing, abstaining from coffee, using a low pillow, weekend sleep habits, use of shower gels, relaxing after stressful events, bus journeys, road stripes, and more.2 The authors of the meta-analysis note that the variability observed likely is because of methodology differences among the studies included in their analysis. For this reason, the authors advised caution in interpreting the results.2

Nevertheless, the investigators concluded that (1) most of those who experience frequent headaches—including migraine sufferers—believe they have at least 1 trigger, and (2) stress is the trigger most frequently cited by patients, followed by sleep and environmental triggers.2

Perceived differences in trigger frequency and strength

Heterogeneity extends beyond the triggers and perceived triggers; incidence and strength also can vary greatly. In a cross-sectional observational study, 300 headache sufferers were asked to rate 33 triggers by frequency and potency.3 Triggers that were perceived to be encountered most days per month were air conditioning and caffeine (both 30 days). Red wine was perceived to be encountered least frequently (0 days). Importantly, interperson variability for frequency of encounter was significant—most ranges for each trigger spanned

15 days or more.3

Triggers that were perceived to increase the chance of a headache were stress (75%), missing a meal, and dehydration (both 60%). Nuts and salty food were least perceived to increase the likelihood of a headache (both 0%). Similar to frequency, perceptions about trigger strengths varied widely, with most ranges spreading by more than 50% for each trigger.3

The authors noted that the heterogeneity seen in frequency of encounters with triggers remained even when 2 patients had matching perceptions about the importance of the trigger in precipitating a headache. The fact that this was observed for nearly every perceived trigger is an important aspect of understanding trigger frequency at the patient-care level.3 Additionally, most headache sufferers do not believe that triggers are simply present or absent. Rather, they have diverse beliefs about the strength of perceived triggers.3 These broad differences among patients make it difficult to predict how an individual headache sufferer will rate triggers.3

The patient’s trigger belief system

Layered onto this challenge is the observation that many migraine sufferers use the so-called trigger belief system to create a safe and controlled environment to stave off headache attacks. Indeed, perception often dictates how headache triggers are experienced, and this adds to the complexity of managing these patients. This is borne out in 2 studies. One, involving more than 200 individuals, revealed that perceived control over and impact of headaches were related to headache severity.4 Another trial involving more than 300 patients seeking treatment for headache showed that participants who were confident they could avoid and better manage their headaches also believed that they could control factors impacting their headaches. Although this led to the use of positive coping strategies, it also triggered more anxiety.5

Trigger avoidance can also lead to reduced quality of life. Consider, for example, physical activity, which is recommended to prevent and manage migraine: As many as 8 in 10 migraine sufferers avoid physical activity because they fear triggering an episode.6 In a recent study, investigators examined the potential correlation between anxiety sensitivity and physical activity avoidance among 100 women with migraine. Participants completed an anonymous survey about migraine and avoiding physical activity. The survey included a tool that measured anxiety sensitivity. Migraine attacks in the previous 30 days were self-reported.6 Higher anxiety scores were linked with more frequent physical activity avoidance. Participants who cited physical concerns were nearly 8 times more likely to avoid vigorous physical activity. Those who mentioned cognitive concerns were more than 5 times more likely to avoid moderate physical activity.6 The authors noted that even though avoiding triggers often is recommended, in some situations it can lead to more migraines because of increased anxiety. For this reason, although avoidance is probably best for certain triggers that have true biologic onset mechanisms, triggers that work through anticipatory anxiety or fearful expectations might best be handled via gradual exposure and desensitization.6

Distinguishing between real triggers and premonitory symptoms

Once clinicians gain an understanding of these factors, they may consider themselves adequately prepared to optimally manage migraine sufferers. Yet, there is one more factor to consider: premonitory symptoms. Separating premonitory symptoms from actual migraine triggers gets the clinician closer to optimal management. Yet, it is not always easy to make the distinction.

Premonitory symptoms typically present 2 to 48 hours (or more) before migraine headache onset. Symptoms include changes in mood and activity, irritability, fatigue, food cravings, repetitive yawning, stiff neck, and photophobia. Because these symptoms can continue even past the premonitory stage, they often can be misinterpreted as actual migraine triggers.7 Premonitory symptoms have been found to accompany 30% to 80% of migraine attacks. Signs that often are confused with actual migraine triggers include neck pain, photophobia, and food cravings.8

Timing of symptoms: Potential clues

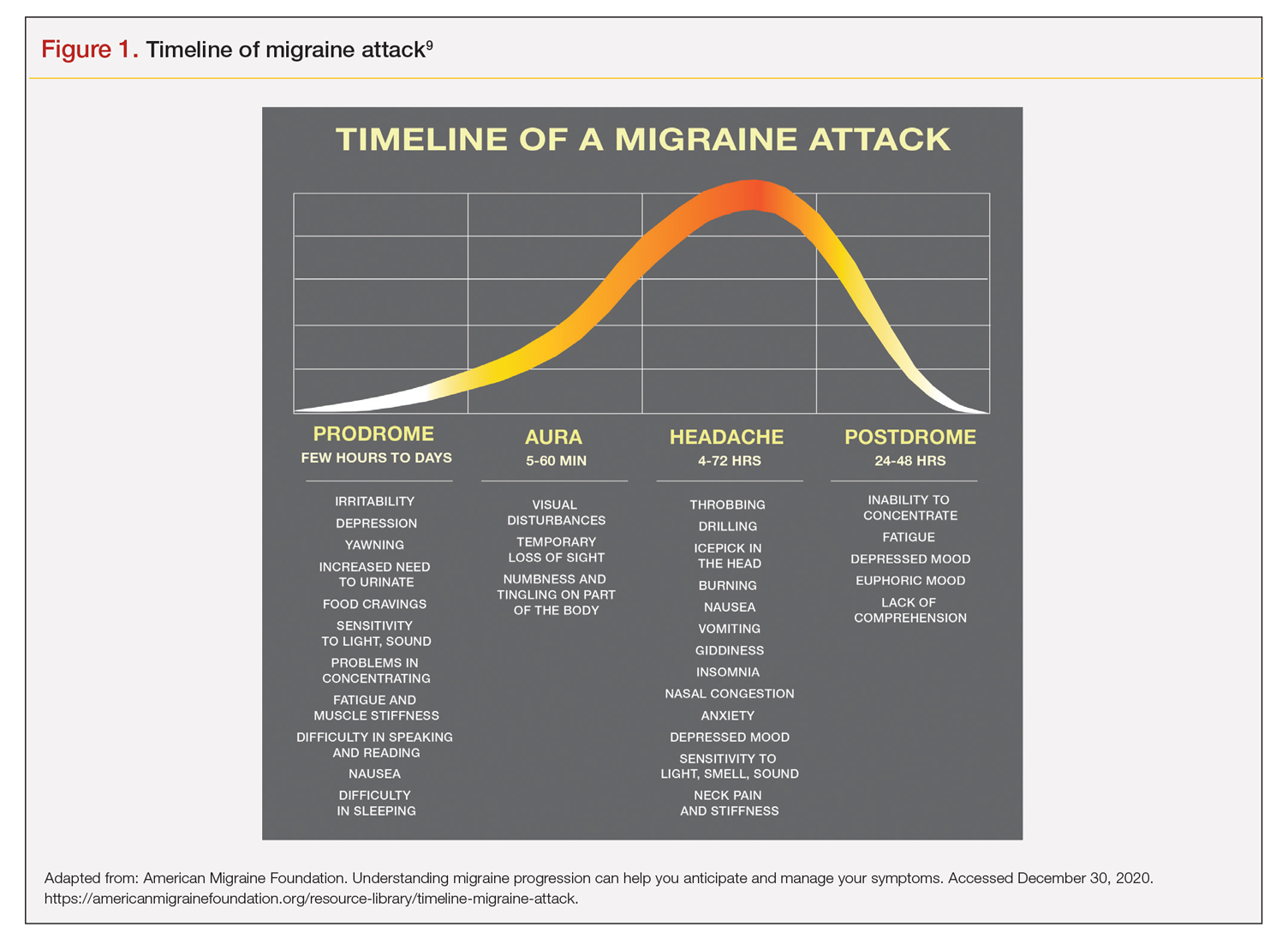

It is critical to understand the interval between a symptom and migraine onset, which can help determine whether it is an actual trigger, premonitory symptom, or other manifestation. For this, it helps to review the timeline of a migraine attack. The 4 phases of a migraine attack—premonitory/prodrome, aura, headache, and postdrome—are well known. According to the American Migraine Foundation, the 4 phases are marked by specific symptoms that typically—but not always—occur along a general timeline (Figure 1).9

Although this symptom timeline can help guide clinicians and migraine sufferers, it is important to understand that these phases do not always occur linearly, and there often is significant overlap, which can mislead both the clinician and patient.7

Common triggers

Stress: Stress is the most frequently self-reported migraine trigger, and numerous studies show a link between stress and migraine. However, retrospective and prospective diary studies have not been able to confirm a link between stressful days and acute migraine attacks. Moreover, although 1 study demonstrated that migraines were less likely to occur on holidays or days off, relaxation did not play a role. Fatigue was more common premigraine than mental exhaustion or insomnia, leading investigators to surmise it is a premonitory symptom and not a migraine cause.8 Further confounding is the finding that reduced stress from one day to the next is linked with migraine onset the next day, making it a possible predictor of a migraine attack because of the so-called letdown effect.10

Menstruation: Menstruation appears to be the most common migraine trigger in women. A large 3-month study showed an increase of migraine prevalence and persistence up to 96%. Additionally, diary studies demonstrate menstruation as a trigger, and in a population-based trial, more than half of female migraine sufferers reported an increased rate

of migraine. However, only 4% actually had a migraine during menstruation.8,11

Diet: Studies that seek to find a link between specific foods and migraine are open to question because they do not have a placebo component, and it is difficult to tell the difference between premonitory food cravings and actual triggers. Moreover, in most patients food appears to be 1 of several contributors to migraine headache, and not the only factor.8 Fasting is among the most studied and consistent migraine triggers and seems to be more common during longer fasts. Dehydration is not thought to be a cause; rather, it could be because of hypoglycemia.8 A trial involving more than 3000 women revealed that those with migraine had a lower diet quality than their counterparts who did not experience migraine. Other smaller studies show benefit from low-fat vegan and ketogenic diets. Also, patients with irritable bowel syndrome and migraine might benefit from eliminating such foods that cause irritation to improve both migraine frequency and bowel symptoms.8

Weather: A few small studies have sought to evaluate the link between weather and migraines. One involving 77 individuals with migraine showed that slightly more than half were sensitive to at least 1 weather factor (i.e., barometric changes, lightning, temperature, and precipitation). Another involving 238 participants demonstrated a nonstatistically significant trend toward increased frequency of migraine attacks on days with high pressure, low wind speed, and increased sunshine, but they called the correlation questionable. A study of 90 individuals found lightning to be an independent risk factor for migraine.8

Sensory stimuli: Although visual, aural, olfactory, and other sensory stimuli have been shown to cause migraine in susceptible individuals and worsen migraine intensity, it is difficult to determine if these are true triggers or premonitory symptoms. Indeed, the discomfort thresholds of various sensory stimuli are lower in migraine sufferers.8 Odors are the most commonly reported triggers among all sensory stimuli. In 1 study, 7 in every 10 migraine sufferers reported that odors triggered their attack. Common offenders include perfumes, paint, gasoline, bleach, and rancid odors. Smoke and exhaust fumes were also found to be problematic.8

Best evidence on migraine triggers

A large retrospective survey looked at acute migraine trigger factors in 1750 individuals treated in a clinical practice. A detailed headache evaluation was conducted that included neurologic history, structured headache interview, and a neurologic exam.12 More than three-fourths of patients experienced triggers. Approximately 6 in every 10 patients had between 4 and 9 triggers. Nearly one-fourth experienced 1 to 3 triggers.12 As shown in Figure 2, the 5 triggers that occurred occasionally in at least half of patients were stress (80%), hormone (65%), fasting (57%), weather (53%), and sleep disturbance (50%). The most common triggers, occurring very frequently, were hormone (33%) and stress (26%).12

Trials that use randomized and blinded exposure to possible triggers can—at face value—appear most useful. Potent compounds such as glyceryl trinitrite, prostaglandin I2 and E2, calcitonin-gene related peptide, and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide have been shown to be dependable triggers in the experimental setting. However, trial designs that do not closely mimic real-world experience lack usefulness in clinical practice. Moreover, studies of low intensity migraine triggers that are common in the real world—chocolate and aspartame, for instance—have produced mixed results.13 So-called N-of-1 studies—in which a single patient is repeatedly exposed in blinded fashion to a trigger or placebo—might be the best way to uncover actual triggers. However, migraine sufferers are, understandably, not interested in deliberately inducing an attack.13

This leaves results of diary studies as the most reflective of clinical practice. These evaluations limit the chance of bias that retrospective studies could carry and often provide a significant amount of real-world data that can be used to test hypotheses. Moreover, the advent of smartphone technology enables researchers to capture data in real time, which can help distinguish premonitory symptoms from actual triggers.13 A high-quality paper diary study (PAMINA) involving 327 individuals showed strong evidence that a migraine was likely to occur with the following factors: menstruation, muscle tension/neck pain, psychic tension, and sunshine that lasted 3 or more hours per day.14

Diary studies are also able to assess the ability of migraine sufferers to predict a headache. In an evaluation that used an electronic diary design, researchers looked at self-prediction through use of a single question asked daily: “How likely are you to have a headache today?” When participants reported at the beginning of a particular day that headache was “almost certain,” actual headache occurred more than 90% of the time on that day.13

Leveraging best evidence into best practices

The clinician–patient conversation

A clinician’s detective skills are put to the test when evaluating patients with migraine. Avoiding dead-ends and fruitless pursuits can spare providers and patients frustration and help patients avoid needless suffering. Yet, as noted, the list of potential triggers appears endless, duration and frequency are variable, patients often try to control their environment with mixed results, and it is difficult to tell the difference between actual triggers and premonitory symptoms.

Which brings us back to Lola H. She desperately wanted to leave her appointment with confidence that she had enough medication to meet her needs each month. She might have expected to go home with access to more medication, but she did not. Rather, she left her clinician’s office with a plan to reduce the number of monthly migraine episodes she experienced, enabling her to use medication as needed, rather than only when her attacks were severe.

Her clinician confirmed that avoiding gasoline odor would reduce the number of attacks. Eliminating chocolates and sweets might, but it is not known whether chocolate is a trigger. He suggested that she try allowing herself chocolate now and then, which would probably serve as a stress reducer. The net result would likely be no change in number of episodes, while allowing for a small improvement in quality of life.

Perhaps most striking, Lola left the appointment certain that her issue with lower barometric pressure was resolved because her clinician took the time to ask how she knew about the daily barometric pressure levels.

Her smartwatch, she told him. He strongly suggested that she delete the watch’s barometric pressure app, which she did on the spot. At her next appointment, Lola was happy to report that barometric pressure no longer played a significant role in her episodes. Moreover, the other strategies she and her clinician discussed have reduced the number of severe and less severe episodes. She no longer lives with the stress of pill-rationing and looks forward to enjoying a small amount of chocolate ice cream each weekend with her family.

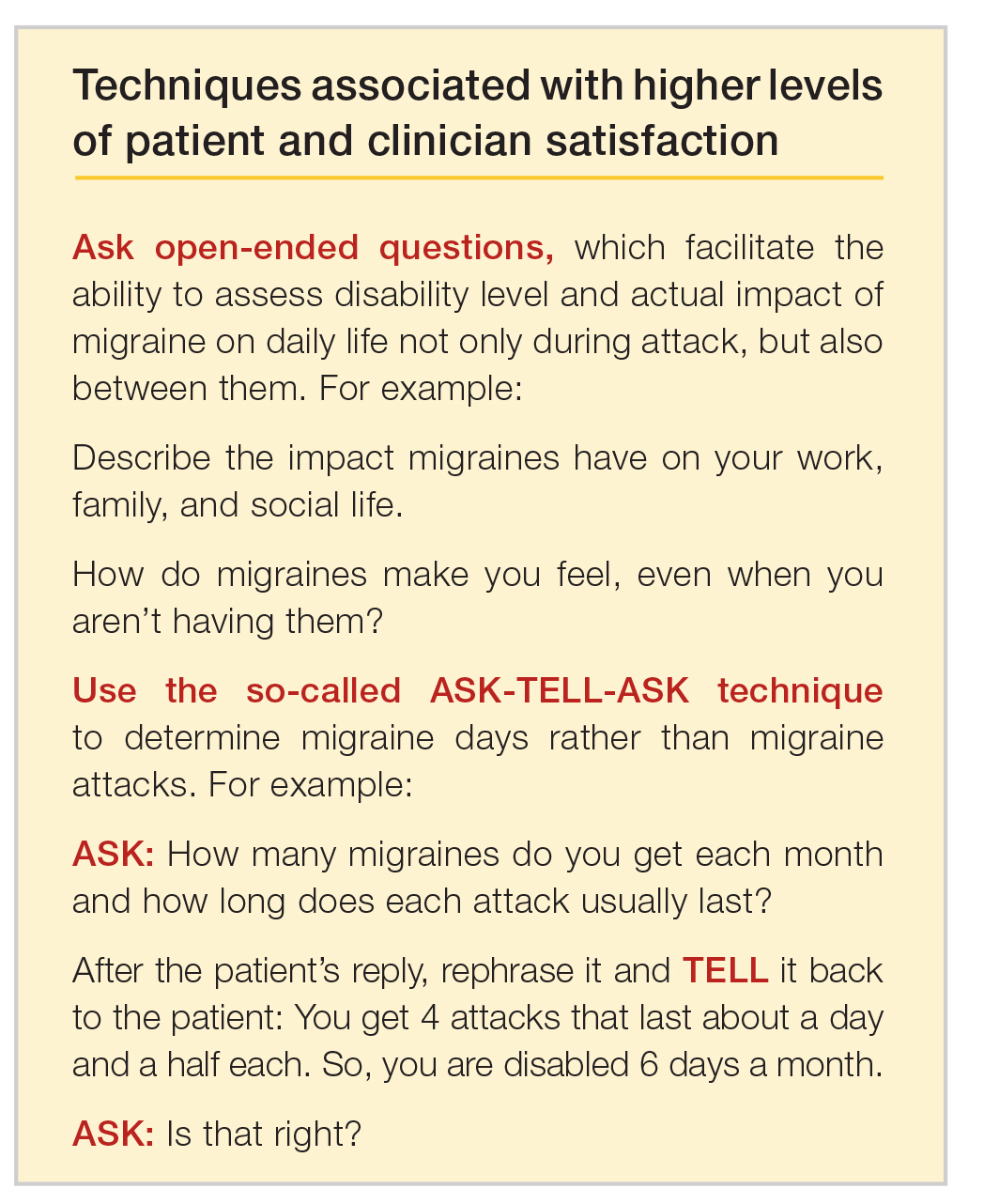

Lola’s case demonstrates that in clinical practice the best way to elicit meaningful responses from migraine sufferers is to ask open-ended questions. Yet, clinicians often fail to do so. In a study evaluating communication strategies between clinicians and 60 long-term migraineurs (average 14 years) who experienced frequent headaches (average 5 per month), 90% of migraine-specific questions asked during an appointment were either close-ended or consisted of a short answer. Postvisit interviews with both clinicians and patients revealed these pairs misaligned on migraine frequency (55% of the time) and impairment (51%). One-third of patients were candidates to receive preventive medication, yet only 20% of them did so. Prevention was not discussed in half of the visits with patients who were candidates to receive preventive therapy but did not get it.10

A panel with extensive experience in migraine reviewed questions from migraine diaries and noted that migraine sufferers find value in capturing wide-ranging information about their condition, whereas clinicians prefer small amounts of data they perceive as relevant to managing migraine.15 It also is reported that the number of questions patients ask is inversely related to the amount of information a clinician gives.16

Recommended strategies

In his review article, Mamura reinforces the concept of open 2-way communication, which involves patients in their care more deeply and reinforces positive habits.8 It is important to be mindful that discussing triggers exclusively can be counterproductive and frustrating for patients, particularly if the conversation is about trigger avoidance. Patients might feel stigmatized by triggers, come away thinking nothing can be done to control them, and become more anxious about impending episodes.8 In fact, a better strategy could be to work with the patient to train their brain to become acclimated to certain triggers or premonitory symptoms, rather than avoiding them.17

Mamura provides a concise summary of 4 best-practice strategies.8 The first 2 should be factored into advice given to patients about migraine triggers and premonitory symptoms; the remaining 2 help frame the treatment approach:

1. Ask patients to keep a headache diary, which eliminates faulty recall and provides a clearer picture of migraine frequency and severity. Include symptoms and other important factors—missed time from work, canceled family activities, nausea and vomiting, etc. Journaling might uncover triggers that can be eliminated or acclimated to via behavior modification. It also can reveal to the patient that certain triggers might not be as useful in predicting migraine as originally thought.

2. Rather than trigger avoidance, suggest that patients concentrate on healthy lifestyle choices, including maintaining healthy weight, getting sufficient sleep, and exercising regularly. The latter has been shown in some studies to work better than preventive medications. Although a behavior change, such as acclimating to certain noises, is not thought to be a healthy lifestyle habit, it ends up being just that if it improves tolerance and reduces migraine episodes.

3. Recognize that many patients have a fear of experiencing a migraine between episodes. If observed in a patient, treat it aggressively. Left unmanaged, this condition could lead to chronic migraine and medication overuse. The right acute medication might be sufficient, but sometimes cognitive-behavioral therapy and biofeedback techniques could be necessary to address behavioral issues that might be interfering with successful treatment.

4. If attacks are frequent and making it difficult to identify distinctive triggers, consider preventive therapy. Patients might resist using preventive medications because they feel eliminating triggers is sufficient, or they might be concerned about medication cost and adverse effects. Eliminating a stressful event alone likely will not help, so it’s important to review with patients—using plain language—how preventive medication treats the underlying cause of migraine and decreases brain excitability, making the patient less prone to attacks.8

Emerging medications

New treatments offer increased options for the acute and preventive treatment of migraine attacks. New acute pharmacologic treatments include gepants and ditans. The gepants target calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), a potent vasodilator and neurotransmitter. During migraine episodes, serum levels of CGRP increase as the peptide is released, modulating the transmission of nociceptive signals from peripheral trigeminal sensory afferents into the central trigeminal system.19 In clinical trials of acute migraine treatment, the gepants provided pain freedom at 2 hours in approximately 20% of attacks, pain relief at 2 hours in 58%, and freedom from the most bothersome symptom at 2 hours in 36% with significant benefit over placebo.20,21 As these oral formulations became available in 2020, there are not enough data on potential long-term adverse events, particularly cardiovascular effects.18 However, the gepants are not associated with medication overuse headache and there is no contraindication to their use in patients with cardiovascular disease. These agents, currently available for oral administration, also show benefit as preventive agents and parenteral formulations are in development.

Ditans target the serotonin 5HT-1F receptor. Triptans target this receptor as well as the 5HT-1B and 5HT-1D receptors. The 5HT-1B receptor action is responsible for constriction of cerebral and peripheral blood vessels that occurs with triptans. Thus, ditans are also options for treating patients with vascular disease. Lasmiditan, the only compound in this class thus far, yielded pain freedom in 2 hours in 31%, pain relief 2 hours in 64%, and relief of the most bothersome symptom at 2 hours in 41%.22 Lasmiditan crosses the blood-brain barrier. Thus, the most common side effects are dizziness, somnolence, and paresthesias, which are generally mild to moderate in severity. Based on driving simulation studies performed in the absence of migraine, patients should not drive within 8 hours of dosing.

Neuromodulation devices are effective options that avoid potential adverse events of systemic treatments. They include external trigeminal nerve stimulation, noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation, remote electrical neuromodulation, caloric vestibular stimulation, and single-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation. Other treatments in development for the acute treatment of migraine include improved parenteral delivery systems and combination oral preparations of existing medications.

Monoclonal antibodies that block the CGRP ligand or its receptor were introduced in 2018, with 4 medications currently available. This is the first class of migraine medications specifically designed for migraine prevention. They are administered parenterally (subcutaneously or intravenously) either monthly or quarterly, depending on the medication. The anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies are indicated for the prevention of episodic and chronic migraine and are eliminated by proteolytic degradation, not involving the liver and reducing the potential for hepatotoxicity and drug-drug interactions.23 A meta-analysis evaluated the subcutaneous formulations studied for chronic migraine, enrolling participants with at least 15 headache days monthly with migraine occurring on at least 8 of those days. In this cohort with a large disease burden, the pooled 50% responder rate 9-12 weeks after administration of the first dose was 37.4% and the 75% responder rate was 12.7%.24 There was also improvement in the number of migraine days, number of days using acute treatment, and total headache hours. The most common side effects were injection site reactions and constipation, with post-marketing reports of hypertension in the compound targeting the CGRP receptor, with or without pre-existing hypertension.25 The safety profile for use during pregnancy was not studied in any of the medications discussed in this section.

Summary

Acute migraine headache is a significant management challenge for neurologists, headache specialists, and other clinicians involved in its treatment. Addressing potential migraine triggers can be a particularly overwhelming task because multiple components and factors play into the disorder. Perceived triggers; their frequency and strength; the effort by patients to control their environment; and the blurred line between real triggers and premonitory symptoms present the clinician with an amalgam of components that must be sorted through, defined, prioritized, and managed. Even though migraine symptoms generally appear along a 4-phase timeline, some symptoms stretch across multiple phases and not all symptoms play out in a linear fashion.

There are specific steps clinicians can take to simplify the process, optimize management, and improve patient outcomes and quality of life. Start by gaining an understanding of common triggers and the best evidence regarding triggers and premonitory symptoms. Use this evidence to modify your approach in practice, if necessary. Specifically:

• Improve the information you gather from patients by asking open-ended questions about their experience during a migraine headache, as well as the period between attacks.

• Rather than having patients tell you how many episodes they experience each month, try to elicit from them how many days per month they feel disabled.

• Ask your patients to keep a headache diary.

• Talk less about trigger avoidance and more about making healthy lifestyle choices.

• Address potential cephalgiaphobia via cognitive-behavioral therapy and biofeedback techniques.

• Consider managing frequent migraine attacks with preventive treatment, which now includes CGRP-targeted medications that are as effective as other agents but have fewer adverse effects and might avoid medication overuse headache.

Dr. Friedman reports being an Advisory Board member for Allergan, Biohaven Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Impel NeuroPharma, Invex, Lundbeck, Revance Therapeutics, Satsuma Pharmaceuticals, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Theranica, and Zosano Pharma. She has received grant support from Allergan, Eli Lilly, Merck, and Zosano Pharma. She is on the Medical Advisory Board for Spinal CSF Leak Foundation, HealthyWomen, and the Board of Directors of the Southern Headache Society. She currently sits on the Editorial Board of Neurology Reviews and has been a contributing author for MedLink Neurology and Medscape.