“Take pride in your surgical work. Do it in such a way that you would be willing to sign your name to it…the operation was performed by me.”

—Raymond A. Lee, MD

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently ordered companies to cease selling transvaginal mesh intended for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) repair (but not for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence [SUI] or for abdominal sacrocolpopexy).1,2 The FDA is also requiring companies preparing premarket approval applications for mesh products for the treatment of transvaginal POP to continue safety and efficacy follow-up in existing section 522 postmarket surveillance studies.3

It is, therefore, incumbent upon gynecologic surgeons to understand the surgical options that remain and perfect their surgical approach to POP to optimize patient outcomes. POP may be performed transvaginally or transabdominally, with each approach offering its own set of risks and benefits. The ability to perform both effectively allows the surgeon to tailor the approach to the condition and circumstances encountered. It is also important to realize that “cures” are elusive in POP surgery. While we can frequently alleviate patient symptoms and improve quality of life, a lifelong “cure” is an unrealistic goal for most prolapse procedures.

This article focuses on transvaginal native tissue repair,4 specifically the Mayo approach.

Watch video here

Vaginal surgery fundamentals

Before we explore the details of the Mayo technique, let’s review some basic principles of vaginal surgery. First, it is important to make a good clinical diagnosis so that you know which compartments (apex, anterior, or posterior) are involved. Although single compartment defects exist, multicompartment defects are far more common. Failing to recognize all compartment defects often results in incomplete repair, which can mean recurrent prolapse and additional interventions.

Second, exposure is critical when performing surgery by any route. You must be able to see your surgical field completely in order to properly execute your surgical approach. Table height, lighting, and retraction are all important to surgical success.

Lastly, it is important to know how to effectively execute your intended procedure. Native tissue repair is often criticized for having a high failure rate. It makes sense that mesh augmentation offers greater durability of a repair, but an effective native tissue repair will also effectively treat the majority of patients. An ineffective repair does not benefit the patient and contributes to high failure rates.

- Mesh slings for urinary incontinence and mesh use in sacrocolpopexy have not been banned by the FDA.

- Apical support is helpful to all other compartment support.

- Fixing the fascial defect between the base of the bladder and the apex will improve your anterior compartment outcomes.

- Monitor vaginal caliber throughout your posterior compartment repair.

Vaginal apex repairs

Data from the OPTIMAL trial suggest that uterosacral ligament suspension and sacrospinous ligament fixation are equally effective in treating apical prolapse.5 Our preference is a McCall culdoplasty (uterosacral ligament plication). It allows direct visualization (internally or externally) to place apical support stitches and plicates the ligaments in the midline of the vaginal cuff to help prevent enterocele protrusion. DeLancey has described the levels of support in the female pelvis and places importance on apical support.6 Keep in mind that anterior and posterior compartment prolapse is often accompanied by apical prolapse. Therefore, treating the apex is critical for overall success.

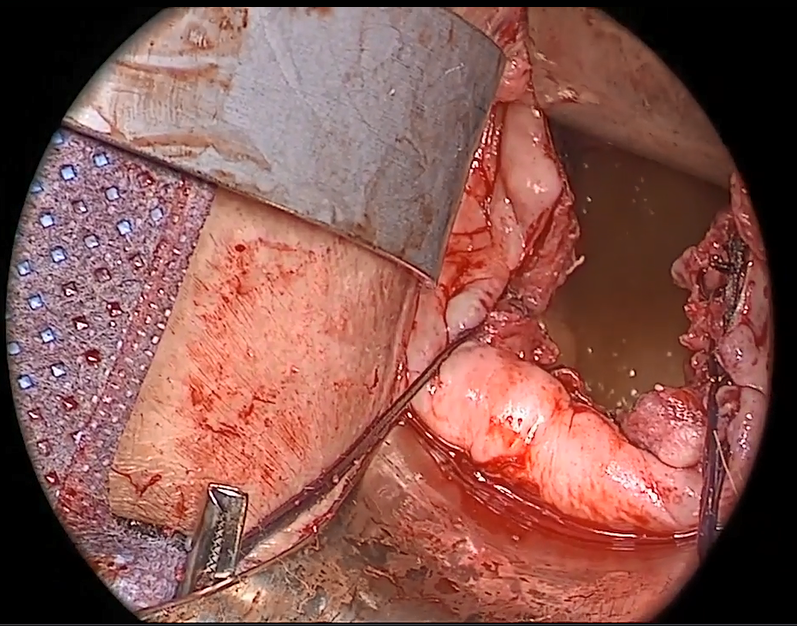

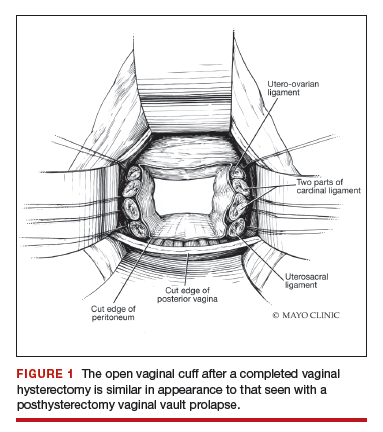

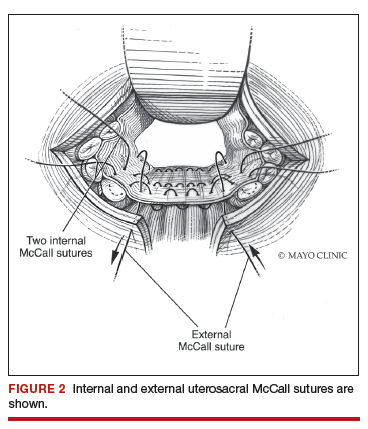

External vs internal McCall sutures: My technique. Envision the open vaginal cuff after completing a vaginal hysterectomy or after opening the vaginal cuff for a posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse (FIGURE 1). External (suture placed through the vaginal cuff epithelium into the peritoneal cavity, incorporating the uterosacral ligaments and intervening peritoneum, and ultimately brought back out through the posterior cuff and tied) or internal (suture placed in the intraperitoneal space, incorporating the uterosacral ligaments and intervening peritoneum, and tied internally) McCall sutures can be utilized (FIGURE 2). I prefer a combination of both. I use 0-polyglactin for external sutures, as the sutures will ultimately dissolve and not remain in the vaginal cavity. I usually place at least 2 external sutures with the lowest suture on the vaginal cuff being the deepest uterosacral stitch. Each subsequent suture is placed closer to the vaginal cuff and closer to the ends of the ligamentous stumps, starting deepest and working back toward the cuff with each stitch. I place 1 or 2 internal sutures (delayed absorbable or permanent) between my 2 external sutures. Because these sutures will be tied internally and located in the intraperitoneal space, permanent sutures may be used.

Avoiding ureteral injury: Tips for cystoscopy. A known risk of performing uterosacral ligament stitches is kinking or injury to the ureter. Therefore, cystoscopy is mandatory when performing this procedure. I tie one suture at a time starting with the internal sutures. I then perform cystoscopy after each suture tying. If I do not get ureteral spill after tying the suture, I remove and replace the suture and repeat cystoscopy until normal bilateral ureteral spill is achieved.

Key points for uterosacral ligament suspension. Achieving apical support at this point gives me the ability to build my anterior and posterior repair procedures off of this support. It is critical when performing uterosacral ligament suspension that you define the space between the ureter and rectum on each side. (Elevation of the cardinal pedicle and medial retraction of the rectum facilitate this.) The ligament runs down toward the sacrum when the patient is supine. You must follow that trajectory to be successful and avoid injury. One must also be careful not to be too deep on the ligament, as plication at that level may cause defecatory dysfunction.

Continue to: Anterior compartment repairs...