Weigel et al prospectively evaluated 200 postmenopausal women with an endometrial echo of 3 to 10 mm and found that homogeneity of the echo, a low echo, and a “sonographically depictable central echo between symmetrical endometrial leaves” were associated with an absence of pathology, while heterogeneity and high echogenicity were associated with pathology.13

During the reproductive years, TVS also is useful in assessing myometrial echotexture, adnexal pathology, and, less consistently, endometrial echo. The endometrial thickness varies daily during a normal menstrual cycle. It is thinnest during menses, increases during the follicular phase, and achieves the greatest endometrial height (10 to 14 mm) during the secretory phase. By correlating these measurements with ovarian activity (corpus luteum vs follicular activity), the physician is better able to assess endometrial morphology observed in the midfollicular and secretory phases. However, ancillary testing with SIS is more sensitive for the detection of intracavitary pathology in these women.

Saline infusion sonography (SIS). With SIS, saline is infused into the endometrial cavity during TVS to enhance the image. Many terms have been used to describe this technique, but I prefer SIS because it defines the technique more precisely.14

SIS allows for more accurate evaluation of the uterus for intracavitary lesions than TVS and makes it easier to differentiate the causes of increased endometrial thickness. Indications for SIS include:

- Abnormal bleeding in premenopausal or postmenopausal patients

- Evaluation of an endometrium that is thickened, irregular, immeasurable, or poorly defined on conventional TVS

- Evaluation of an endometrium that appears irregular on TVS in women on tamoxifen

- Differentiating between sessile and pedunculated masses of the endometrium

- Preoperative evaluation of intracavitary fibroids

Increasingly, gynecologists are embracing the concept of “one-stop” evaluation for menstrual disorders by combining the physical exam and basic laboratory studies (CBC and thyroid-stimulating hormone [TSH]) with TVS unless the clinical history dictates otherwise. However, when TVS is indeterminate, SIS should be performed. Also, all women over 40 who have a suspicious TVS exam should undergo SIS and endometrial biopsy. When such evaluation suggests endometrial polyps or submucosal fibroids, the patient needs operative intervention instead of medical therapy, the patient can be referred directly to a surgeon.

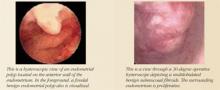

Hysteroscopy. Office hysteroscopy has revolutionized the practice of gynecology. Thin operative hysteroscopes with outer diameters ranging from 3 to 5 mm can be utilized comfortably in an office setting. The procedure permits full visualization of the endometrial cavity and endocervix and facilitates the accurate diagnosis of atrophy, endometrial hyperplasia, polyps, fibroids, and endometrial cancer. Directed endometrial biopsies are possible with some hysteroscopes.

Office hysteroscopy accurately diagnoses many endometrial lesions associated with abnormal bleeding. When the endometrial cavity appears normal at hysteroscopy, aggressive medical therapy should be considered.

Surgical options

Among the surgical treatments for abnormal uterine bleeding are myomectomy, polypectomy, endometrial ablation, and hysterectomy. Dilatation and curettage (D&C), commonly used in the past to treat menstrual aberrations, is no longer preferred. D&C is highly inaccurate, resulting in missed diagnoses, incomplete removal of intracavitary pathology, and a high false-negative rate.15 Operative hysteroscopy with directed endometrial sampling is now the gold standard for surgical evaluation of the uterine cavity. With it, full evaluation is possible even in the presence of heavy bleeding; coexisting intrauterine pathology also can be removed. Because the range of surgical options has broadened in recent years, hysterectomy should be the last resort.

To a large extent, the best surgical modality for a given patient depends on her specific pathology, fertility, and contraceptive needs.

Normal uterine cavity. Endometrial ablation typically is offered after failed medical therapy in women with a normal uterine cavity and negative laboratory workup, provided they have completed childbearing. Hysteroscopic and global endometrial ablation procedures destroy the endometrium, preventing regeneration. This creates Asherman’s syndrome, which leads to hypomenorrhea, eumenorrhea, or amenorrhea.

Endometrial ablation is an outpatient procedure associated with a rapid return to work, minimal complications, and high patient satisfaction. Approximately 20% to 30% of patients undergoing endometrial ablation will become amenorrheic, 65% to 70% will become hypomenorrheic, and 5% to 10% of the procedures will fail. Approximately 30% of patients treated by endometrial ablation will require a subsequent operation.16

If the woman wants to preserve her fertility, I generally order magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to rule out adenomyosis, since TVS, SIS, and hysteroscopy usually cannot detect it. Adenomyosis can be focal or diffuse and is associated with irregular menses and dysmenorrhea. I also suggest an aggressive trial of medical therapy for at least 3 or 4 cycles, with extensive laboratory evaluation. That is, if the history is suggestive of systemic disease, I order liver function tests. If renal disease is suspected, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels are helpful, as are luteinizing hormone (LH), FSH, and androgen levels to diagnose PCOS. Adrenal function tests (cortisol, 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone [17-OHP]) are useful in the diagnosis of hyperandrogensim with suspected adrenal tumors, and congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) is diagnosed by an abnormal 17-OHP level.