Article

How can pregnant women safely relieve low-back pain?

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER: ACETAMINOPHEN IS SAFE for use in pregnancy but lacks evidence of efficacy (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C, usual...

Jaimey M. Pauli, MD, is Assistant Professor, Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Penn State University College of Medicine, and Attending Perinatologist at the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pennsylvania.

John T. Repke, MD, is University Professor and Chairman of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Penn State University College of Medicine. He is also Obstetrician-Gynecologist-in-Chief at the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pennsylvania. Dr. Repke serves on the OBG Management Board of Editors.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

ACOG aims to clarify best practices in managing hypertension in pregnancy. Here, changes to note. PLUS, "Don't throw out that CVS kit just yet!"

Over the past 20 years, the incidence of preeclampsia in the United States has increased 25%,1 and the disorder is a leading cause of morbidity and death among both mothers and infants. Although considerable progress has been achieved in elucidating the pathophysiology of preeclampsia, greater understanding has not yet carried over into improved clinical practice.

To address this disconnect between data and practice, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) issued a 99-page document in November 2013 to help establish best practices in the diagnosis and management of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. We begin this article with a look at its major recommendations.

Other notable developments in obstetrics over the past year have been the rapid evolution of noninvasive prenatal testing and the publication of new guidance on screening, diagnosis, and management of gestational diabetes, all of which are addressed in this article.

ACOG AIMS TO CLARIFY BEST PRACTICES IN THE MANAGEMENT OF HYPERTENSION IN PREGNANCY

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in Pregnancy. Washington, DC: ACOG; November 2013.

The biggest news of the past year is probably the November 2013 report on hypertension in pregnancy from ACOG, which was developed with three goals in mind:

to summarize current knowledge

to provide best-practice guidelines

to identify areas in which further research is needed.

The classification, diagnosis, prediction, prevention, and management of gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, and chronic hypertension are addressed in the report. Although space constraints prevent us from summarizing the entire document, we would like to highlight the biggest changes and most relevant additions to clinical practice.

Notable recommendations

Classification. Preeclampsia is no longer characterized as “mild” or “severe” but as “preeclampsia without severe features” and “preeclampsia with severe features.” As justification for these changes, the ACOG Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy noted that preeclampsia is progressive by nature, so a characterization of “mild” disease is appropriate only at the time of diagnosis. Therefore, “appropriate management mandates frequent reevaluation for severe features.”

Diagnosis of proteinuria. The options are a 24-hour urine collection demonstrating more than 300 mg of protein or a single-specimen urine protein:creatinine ratio of 0.3 mg/dL or higher. Dipstick values should only be used if these quantitative measures are unavailable.

Signs of severe disease. Fetal growth restriction and proteinuria of more than 5 g/24 hr are no longer considered defining features of severe disease.

Severe features now include any of these:

systolic blood pressure (BP) of 160 mm Hg or higher, or diastolic BP of 110 mm Hg or higher on two occasions at least 4 hours apart while the patient is on bed rest (unless antihypertensive therapy is initiated before this time)

thrombocytopenia (platelets <100 x 109/L)

impaired liver function, as indicated by abnormally elevated blood concentrations of liver enzymes (to twice normal concentration) and/or severe, persistent right upper quadrant or epigastric pain unresponsive to medication and not accounted for by alternative diagnoses

progressive renal insufficiency (serum creatinine concentration >1.1 mg/dL or a doubling of the serum creatinine concentration in the absence of other renal disease)

pulmonary edema

new-onset visual or central nervous system disturbances.

Related Article: Does an unfavorable cervix preclude induction of labor at term in women who have gestational hypertension or mild preeclampsia? George Macones, MD (Examining the Evidence, December 2012)

Screening for preeclampsia. The use of Doppler studies and serum biomarkers is not recommended, as there is no evidence that early identification translates to improved outcomes.

Prevention of preeclampsia. Low-dose aspirin (60–80 mg/d, starting in the late first trimester) should be offered as primary prevention to:

women with a history of early-onset preeclampsia and delivery before 34 weeks’ gestation

women with a history of preeclampsia in multiple pregnancies

other high-risk patients (chronic hypertension, diabetes).

No other treatments (vitamin C or E, salt restriction, or bed rest) are recommended for the prevention of preeclampsia, although calcium supplementation may be recommended for women with a low baseline dietary intake of calcium.

Use of magnesium sulfate. Universal prophylaxis with magnesium sulfate is not recommended for preeclampsia unless severe features are present or the patient’s clinical condition changes to severe during labor.

Timing of delivery. Recommendations for delivery for patients with hypertensive disorders are:

gestational hypertension or preeclampsia without severe features: 37 weeks’ gestation

preeclampsia with severe features: by 34 weeks

chronic hypertension: not before 38 weeks

chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia: 34 or 37 weeks, depending on the presence of severe features.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER: ACETAMINOPHEN IS SAFE for use in pregnancy but lacks evidence of efficacy (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C, usual...

It is higher after elective primary cesarean.

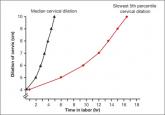

We are in a new era. Our patients, and their labors, have changed on a global scale. To optimally manage labor you need to use these new norms in...

Vaccination coverage is only around 50% for pregnant women

No. This post hoc analysis from the Hypertension and Preeclampsia Intervention Trial at Term (HYPITAT) found that, contrary to widely held belief...