Article

How can pregnant women safely relieve low-back pain?

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER: ACETAMINOPHEN IS SAFE for use in pregnancy but lacks evidence of efficacy (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C, usual...

Jaimey M. Pauli, MD, is Assistant Professor, Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Penn State University College of Medicine, and Attending Perinatologist at the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pennsylvania.

John T. Repke, MD, is University Professor and Chairman of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Penn State University College of Medicine. He is also Obstetrician-Gynecologist-in-Chief at the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pennsylvania. Dr. Repke serves on the OBG Management Board of Editors.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

All of these recommendations are contingent upon the clinical status of the patient and her fetus. For example, if the fetus develops severe growth restriction (<5%) or oligohydramnios, delivery may be recommended regardless of gestational age, based on fetal testing and maternal stability.

Related Article: A stepwise approach to managing eclampsia and other hypertensive emergencies Baha M. Sibai (October 2013)

Postpartum hypertension. The need for recognition of hypertension in the postpartum period is emphasized, as well as appropriate management, using the following guidelines:

Be aware that BP decreases initially after delivery and then increases 3 to 6 days postpartum, requiring vigilance on the part of the clinician. For this reason, BP monitoring is recommended 72 hours postpartum (inpatient or outpatient) and again in 7 to 10 days in women diagnosed with a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy.

Counsel patients who experience a hypertensive disorder and/or preeclampsia during pregnancy about postpartum preeclampsia, providing strict precautions and explicit instructions regarding its signs and symptoms

If BP remains elevated after the first postpartum day, consider discontinuing nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), as they may be related to hypertension

Treat BP that remains above 150/100 mm Hg with antihypertensive therapy

If postpartum preeclampsia is suspected, administer magnesium sulfate for 24 hours.

A culture shift is needed

At our institution, the most significant potential changes to clinical practice may be the elimination of universal magnesium sulfate prophylaxis and the removal of severe fetal growth restriction from the definition of “severe” preeclampsia.

Also, because the use of NSAIDs is widespread for postpartum pain control, a culture change is needed if we are to follow the postpartum recommendations.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

Although we suggest that you read the ACOG report thoroughly, remember that its recommendations are only that—recommendations. Also keep in mind that only six of the approximately 60 “recommendations” provided in this report were accompanied by both high-quality evidence and a strong recommendation. There still is room for clinical judgment and individualization of management to specific patient populations.

NONINVASIVE PRENATAL SCREENING IS EXPANDING RAPIDLY—BUT DON’T THROW OUT THAT CVS KIT JUST YET!

ACOG Committee on Genetics.Committee Opinion #545: Noninvasive prenatal testing for fetal aneuploidy. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(6):1532–1534.

Mennuti MT, Cherry AM, Morrissette JJD, Dugoff L. Is it time to sound an alarm about false-positive cell-free DNA testing for fetal aneuploidy? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(5):415–419.

In last year’s Update in Obstetrics, we discussed noninvasive prenatal genetic screening via cell-free fetal DNA, noting that it is a safer (no risk of miscarriage) and faster (starting at 10 weeks’ gestation) way to screen for aneuploidy. The sensitivity and specificity of this test for Trisomy 21 and 18 are over 99%, with slightly lower sensitivity for Trisomy 13 and sex chromosome abnormalities and a false-positive rate of 0.5%.

In a committee opinion published in December 2012, ACOG concluded that

cell-free fetal DNA is an appropriate screening option only for specific groups of patients at risk for aneuploidy:

women older than age 35

women with fetal ultrasonography findings that are concerning for aneuploidy

women with aneuploidy in a prior pregnancy

women with abnormal first- or second-trimester genetic screening tests

parents with a balanced translocation and an increased risk of Trisomy 21 or 13.

Noninvasive aneuploidy testing is for screening only

Negative results are not diagnostic, and all positive results should be confirmed with invasive testing (chorionic villus sampling [CVS] or amniocentesis).

ACOG does not recommend routine use of cell-free fetal DNA without a comprehensive history and adequate patient counseling, as well as a designation of “high risk.”

Over the past year, more options have become available for aneuploidy screening via cell-free fetal DNA, including screening in twin gestations (for Trisomy 21, 18, 13, and the presence of a Y chromosome only) and screening for:

22q deletion (DiGeorge syndrome)

5p– (Cri-du-chat syndrome)

15q (Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes)

1p (1p36 deletion syndrome)

Trisomy 16

Trisomy 22.

At this rate, the genetic information potentially available via noninvasive testing seems unlimited. It is easy to see how the fact that this is a screening test—not a diagnostic test—could get lost in the excitement.

Other limitations: Noninvasive testing is still not validated in low-risk patients, and the false-positive risk may be higher than original estimates.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER: ACETAMINOPHEN IS SAFE for use in pregnancy but lacks evidence of efficacy (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C, usual...

It is higher after elective primary cesarean.

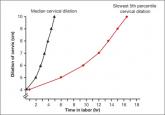

We are in a new era. Our patients, and their labors, have changed on a global scale. To optimally manage labor you need to use these new norms in...

Vaccination coverage is only around 50% for pregnant women

No. This post hoc analysis from the Hypertension and Preeclampsia Intervention Trial at Term (HYPITAT) found that, contrary to widely held belief...