providing early intervention and accessing community resources, according to a clinical report from the American Academy of Pediatrics.

After the AAP released its guidelines on fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) in 2015, some pediatricians asked for further guidance on how to care for patients with FASD within the medical home, as many had a knowledge gap on how to best manage these patients.

“For some pediatricians, it can seem like a daunting task to care for an individual with an FASD, but there are aspects of integrated care and providing a medical home that can be instituted as with all children with complex medical diagnoses,” wrote Renee M. Turchi, MD, MPH, of the department of pediatrics at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children and Drexel Dornsife School of Public Health in Philadelphia, and her colleagues on the AAP Committee on Substance Abuse and the Council on Children with Disabilities. Their report is in Pediatrics. “In addition, not recognizing an FASD can lead to inadequate treatment and less-than-optimal outcomes for the patient and family.”

Dr. Turchi and her colleagues released the FASD clinical report with “strategies to support families who are interacting with early intervention services, the educational system, the behavioral and/or mental health system, other community resources, and the transition to adult-oriented heath care systems when appropriate.” They noted the prevalence of FASD is increasing, with 1 in 10 pregnant women using alcohol within the past 30 days and 1 in 33 pregnant women reporting binge drinking in the past 30 days. They reaffirmed the AAP’s endorsement from the 2015 clinical report on FASD regarding abstinence of alcohol for pregnant women, emphasizing that there is no amount or kind of alcohol that is risk free during pregnancy, nor is there a time in pregnancy when drinking alcohol is risk free.

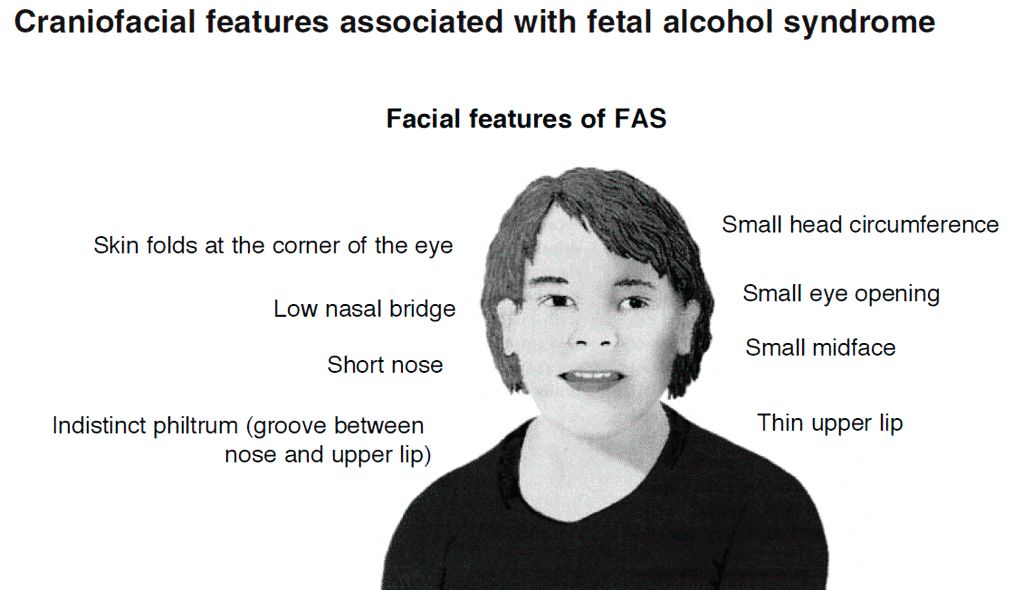

Providers in a medical home should communicate any prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) to obstetric providers so they can review risk factors, optimize screening, and monitor children, Dr. Turchi and her colleagues said. They also should understand the diagnostic criteria and classifications for FASDs, including physical features such as low weight, short palpebral features, smooth philtrum, a thin upper lip, abnormalities in the central nervous system, and any alcohol use during pregnancy. Any child – regardless of age – is a candidate for universal PAE screening at initial visits or when “additional cognitive and behavioral concerns arise.”

The federal Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act “does not require clinicians to report to child protective services if a child has been exposed prenatally to alcohol (i.e., for a positive PAE screening result). Referral to child protective services is required if the child has been diagnosed with an FASD in the period between birth and 3 years. The intent of this referral is to develop safe care and possible treatment plans for the infant and caregiver if needed, not to initiate punitive actions,” according to the report. States have their own definitions about child abuse and neglect, so the report encourages providers to know the mandates and reporting laws in the states where they practice.

Monitoring children in a medical home for the signs and symptoms of FASD is important, the authors said, because research has shown an increased chance at reducing adverse life outcomes if a child is diagnosed before age 6 and is in a stable home with access to support services.

Management of children with FASD is individual, as symptoms for each child will uniquely present not just in terms of physical issues such as growth or congenital defects affecting the heart, eyes, kidneys, or bones, but also as developmental, cognitive, and behavioral problems. Children with FASD also may receive a concomitant diagnosis when evaluated, such as ADHD or depression, that will require additional accommodation. The use of evidence-based diagnostic and standard screening approaches and referring when necessary will help reevaluate whether a child has a condition such as ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, or another diagnosis, or is displaying symptoms of FASD such as a receptive or expressive language disorder.

Pediatricians must work together with the families, educational professionals, the mental health community, and therapists to help manage FASD in children. In cases where a child is in foster care, partnering with the foster care partners and child welfare agencies to gain access to the medical information of the biological parents is important to determine whether there is parental history of substance abuse and to provide appropriate treatment and interventions.

“Given the complex array of systems and services requiring navigation and coordination for children with an FASD and their families, a high-quality primary care medical home with partnerships with families, specialists, therapists, mental and/or behavioral health professionals, and community partners is critical, as it is for all children with special health care needs,” Dr. Turchi and her colleagues said.

The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Turchi RM et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Sept 10. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-2333.