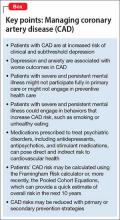

The problem is enormous: Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the United States, and coronary artery disease (CAD) is the most common form of heart disease—responsible for 385,000 deaths in the United States in 2009 (http://www.cdc.gov/heartdisease/facts. htm). Patients with psychiatric illness have higher rates of morbidity and mortality from CAD than the general population, and warrant consideration as a special population. You should be familiar with routine cardiac medications; your patients’ medical problems; potential cardiac-related interactions among their psychotropic medications; and interactions among illnesses in their mental health and medical health domains (Box).

CASE Type 2 diabetes mellitus plus a long history of heavy smoking

Ms. S, age 57, is an African American woman with chronic paranoid schizophrenia who has been seeing a psychiatrist for the past 10 years. Ms. S’s psychiatric symptoms have been well controlled on risperidone, 3 mg/d.

Ms. S has a family history of diabetes, hypertension, and early CAD (a brother died of a myocardial infarction [MI] in his late 40s). She continues to smoke 2 packs of unfiltered cigarettes daily, as she has done for the past 40 years.

The psychiatrist has been following American Diabetes Association/American Psychiatric Association guidelines for monitoring; he has noticed that Ms. S’s body mass index (BMI) has increased from 27 to 31 kg/m2 over the past year. She has developed type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

At today’s visit, Ms. S arrives a few minutes late and appears flustered and out of breath. She explains that she had to climb a flight of stairs to get to office because the elevator is broken.

During the visit, the psychiatrist notes that Ms. S occasionally winces and massages her left shoulder.

Questions to ponder

• What else could the psychiatrist do to modify Ms. S’s cardiac risk factors?

• What is Ms. S’s 10-year risk of an acute coronary event?

• What should her physician do now?

Overview: Cardiac risk in patients with mental illness

Modifiable risks for CAD include hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, T2DM, obesity (all of which, taken together, constitute the metabolic syndrome), smoking, and a sedentary lifestyle. Some risk factors, including sex, age, and family history, are not modifiable. Whether or not this modification leads to better outcomes, psychiatric comorbidity is associated with higher morbidity and mortality from CAD.

Whether a common underlying pathological process manifesting in both CAD and mental illness exists, or whether the association is causal, are not well understood. Symptoms characteristic of depression (apathy, amotivation) and schizophrenia (disorganization, paranoia) could lead to poor self-care or impaired adherence to programs designed to lower CAD risk factors.1,2

People with mental illness smoke at a higher rate than those who do not have mental illness.3 This finding is of particular relevance because smoking contributes to worse outcomes with respect to CAD, even when medications are prescribed to address metabolic risks.4

Lower socioeconomic status is associated with poorer prognosis from CAD5 and is a risk factor for depression.6 Depression is a strong independent predictor of worse survival in acute coronary syndromes.5 Some experts consider depression to be a stronger risk factor for MI than traditional medical risk factors such as obesity, hypertension, and second-hand smoke.7

Interventions used to treat certain mental illnesses can exacerbate, or predispose to, metabolic syndrome (which, in turn, increases the risk of CAD). Although some studies have demonstrated metabolic derangements in medication-naïve patients who have a new diagnosis of schizophrenia,8 there is a clearly established association between second-generation antipsychotic use and obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and T2DM. This association prompted development in 2004 of consensus recommendations for cardiovascular monitoring of patients who are taking an atypical antipsychotic.9

Some studies suggest that the stress of mental illness contributes to the pathogen esis of CAD.8 Hypothesized mechanisms include:

• sympathetic activation

• vagal deactivation

• platelet activation

• hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical pathways

• anticholinergic mechanisms

• inflammatory mediators, including cytokines.

Mental stress itself has the capacity to induce coronary ischemia.10 The mental stress of psychiatric illness could have an important pathophysiologic role in CAD. It can be tempting to disregard chest pain in a patient who is known to have panic disorder, but that patient might in fact be experiencing stress-induced myocardial ischemia.11

As many as 30% to 40% of patients with CAD suffer from clinically significant symptoms of depression; as many as 20% of patients with CAD meet criteria for major depressive disorder, compared with 5% to 10% of people who do not have CAD.2 Depression post-MI has been associated with a higher rate of sudden cardiac death and worse outcomes.12