Case Reports

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: An Emerging Infectious Disease in Travelers

Leishmaniasis describes any of 3 diseases caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Leishmania, the most common of which is cutaneous...

From the University of Iowa, Iowa City. Ms. Seline is from the Carver College of Medicine and Dr. Swick is from the Departments of Dermatology and Pathology. Dr. Swick also is from the Iowa City VA Health Care System.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Correspondence: Brian L. Swick, MD, University of Iowa, Department of Dermatology, 200 Hawkins Dr, 40025 PFP, Iowa City, IA 52242 (swickbrian@yahoo.com).

Syphilis often is referred to as the “great imitator” due to the protean presentations of secondary-stage disease, the most common of which are skin manifestations. Early and accurate diagnosis of syphilis is critical to avoid the morbidity associated with advanced disease. The differential diagnosis includes arthropod assault, chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus, fixed drug eruption, and pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta.

Syphilis often is referred to as the “great imitator” due to the protean presentations of secondary-stage disease, the most common of which are skin manifestations.1 Secondary syphilis typically begins 3 to 10 weeks after initial exposure due to systemic dissemination of Treponema pallidum, and although presentations can vary widely, the classic presentation includes nonspecific generalized symptoms (eg, fever, malaise, lymphadenopathy), variable skin findings (eg, nonpruritic papulosquamous eruption), and mucosal ulcerations or plaques.1 Early and accurate diagnosis of syphilis is critical to avoid the morbidity associated with advanced disease.

The classic histopathologic appearance of secondary syphilis is characterized by psoriasiform epidermal changes; a dermal inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells in a lichenoid and/or superficial and deep perivascular distribution (Figure 1); and endothelial swelling of dermal blood vessels.1 The presence of plasma cells in the infiltrate (Figure 2) is particularly useful for differentiating secondary syphilis from other clinicopathological mimickers, but this finding is not always present. Silver-based histochemical stains (eg, Warthin-Starry silver stain) can be used to high-light T pallidum organisms; however, histochemical staining is plagued by low diagnostic sensitivity for identifying the causative organism, making immunohistochemical and/or serologic testing the preferred method for confirming the diagnosis.1

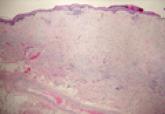

Arthropod assault is characterized by a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate with a variable number of polymorphonuclear cells.2 Overlying spongiosis or focal epidermal necrosis and increased eosinophils are typical of arthropod assault (Figure 3).2 The infiltrate seen following insect bites is classically described as wedge-shaped, although recent literature has disputed the sensitivity of this finding, identifying adnexal structure involvement as an alternative sensitive marker for identifying insect bites.2

Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus demonstrates a spectrum of histopathologic changes depending on the age of the lesion biopsied; however, characteristic histopathologic features typically include variable epidermal atrophy or acanthosis with basal layer vacuolar degeneration, basement membrane thickening, follicular plugging, superficial and deep perivascular and periappendageal lymphocytic inflammation, and dermal mucin deposition (Figure 4).4

Fixed drug eruption histopathologically presents as an interface tissue reaction–associated single-cell necrosis to broader areas of epidermal necrosis, as well as superficial to mid-dermal lymphocytic infiltrate. Unlike secondary syphilis, a fixed drug eruption is characterized by prominent melanin pigment incontinence and eosinophils (Figure 5).5

Similar to secondary syphilis, pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) demonstrates variable psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with a lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Other findings in PLEVA include parakeratosis, variable epidermal necrosis, and prominent exocytosis of lymphocytes. Unlike typical secondary syphilis, PLEVA often is associated with lymphocytic vasculitis, consisting of the invasion of vessel walls by lymphocytes with extravasation of erythrocytes and an absence of conspicuous plasma cells (Figure 6).6

Leishmaniasis describes any of 3 diseases caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Leishmania, the most common of which is cutaneous...

Desmoplastic melanoma, an uncommon variant of melanoma, poses a diagnostic challenge to the clinician because the tumors frequently appear as...