RULES FOR TAKING HYPOTHYROID MEDICATIONS

Thyroid hormone replacement has a narrow therapeutic index, and a subtle change in dosage can significantly alter the therapeutic target. Hypothyroid medications are absorbed in the jejunum/ileum, and an acidic pH in the stomach is optimal for thyroid absorption.3 Therefore, taking the medication on an empty stomach (fasting) with a full glass of water and waiting at least one hour before breakfast is recommended, if possible. An alternate option is to take it at bedtime, at least three hours after the last meal. Taking medication along with food, especially high-fiber and soy products, can decrease absorption of thyroid hormone, which may result in an unstable thyroid function test.

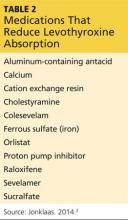

There are supplements and medications that can decrease hypothyroid medication absorption; it is recommended that patients separate these medications by four hours or more in order to minimize this interference. A full list is available in Table 2, but the most commonly encountered are iron supplements, calcium supplements, and proton pump inhibitors.2

In many patients—especially the elderly and those with multiple comorbidities that require polypharmacy—it can be very challenging, if not impossible, to isolate thyroid medication. For these patients, recommend that they be “consistent” with their routine to ensure they achieve a similar absorption rate each time. For example, a patient’s hypothyroid medication absorption might be reduced by 50% by taking it with omeprazole, but as long as the patient consistently takes the medication that way, she can have stable thyroid function.

NEW MEDICATION REGIMEN OR MEDICAL CONDITION

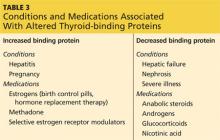

In addition to medications that can interfere with the absorption of thyroid hormone replacement, there are those that affect levels of thyroxine-binding globulin. This affects the bioavailability of thyroid hormones and alters thyroid status.

Thyroid hormones such as thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) are predominantly bound to carrier proteins, and < 1% is unbound (so-called free hormones). Changes in thyroid-binding proteins can alter free hormone levels and thereby change TSH levels. In disease-free euthyroid subjects, the body can compensate by adjusting hormone production for changes in binding proteins to keep the free hormone levels within normal ranges. However, patients who are at or near full replacement doses of hypothyroid medication cannot adjust to the changes.

In patients with hypothyroidism who are taking thyroid hormone replacement, medications or conditions that increase binding proteins will decrease free hormones (by increasing bound hormones) and thereby raise TSH (hypothyroid state). Vice versa, medications and conditions that decrease binding protein will increase free hormones (by decreasing bound hormones) and thereby lower TSH (thyrotoxic state). Table 3 lists commonly encountered medications and conditions associated with altered thyroid-binding proteins.1

It is important to consider pregnancy in women of childbearing age whose TSH has risen for no apparent reason, as their thyroid levels should be maintained in a narrow therapeutic range to prevent fetal complications. Details on thyroid disease during pregnancy can be found in the April 2015 Endocrine Consult, “Managing Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy.”

In women treated for hypothyroidism, starting or discontinuing estrogen-containing medications (birth control pills or hormone replacement therapy) often results in changes in thyroid status. It is a good practice to inform the patient about these changes and to recheck her thyroid labs four to eight weeks after she starts or discontinues estrogen, adjusting the dose if needed.

Continue for changes in manufacturer/brand >>